To get to Lavecon, I took the midlands train from London/Euston up toward Birmingham, and got off at Northampton. On the way up, I went past Bletchley, the home of Bletchley Park – where the British code-breakers (including Alan Turing) worked during WWII.

Lavecon was kind of small, and hot, and after the first day I was ready to move on. So I had breakfast, checked out of the hotel, and walked to the train station. Unfortunately the railway line was down so we were all loaded onto a bus that (judging by the smell) had non-working air conditioning and a leaky loo. I travel a great deal and have developed a technique of putting myself into a light trance, which makes time and discomfort simply disappear. An hour or so later, I was at Milton Keynes, then on the train quay in the sweet fresh air, for a 10 minute train ride to Bletchley. The Park is only a few hundred yards from the station, so I slouched off down the road.

Lavender is one of my favorite scents, so I stopped to stick a couple blossoms into my Fuel Rats ball cap.

WWII-era stuff seems incredibly distant to me, but it’s really only a few decades before I was born. I suppose that’s a side effect of changing times, pictures of New York in the 60s look “vintage” yet familiar, but Britain in the war was pretty stripped down. The amenities at the welcome station were all very WWII-looking, though new. It wasn’t “Hollywood new” like we’d have in the US – foamed urethane prop-doors; everything was real wood though the paint was in muted pre-faded colors. The helpful fellow at the front desk was desperate to give me a discount, and asked it I was a senior citizen (I growled a bit) and then a veteran. “Uh, yes.” He brightly said, “Well, then, that’s 20% off! Thank you for your service!” I told him my service was not satisfactory to anyone, though I did have an honorable, at which he looked quizzical, stopped trying to be appreciative, and let me in.

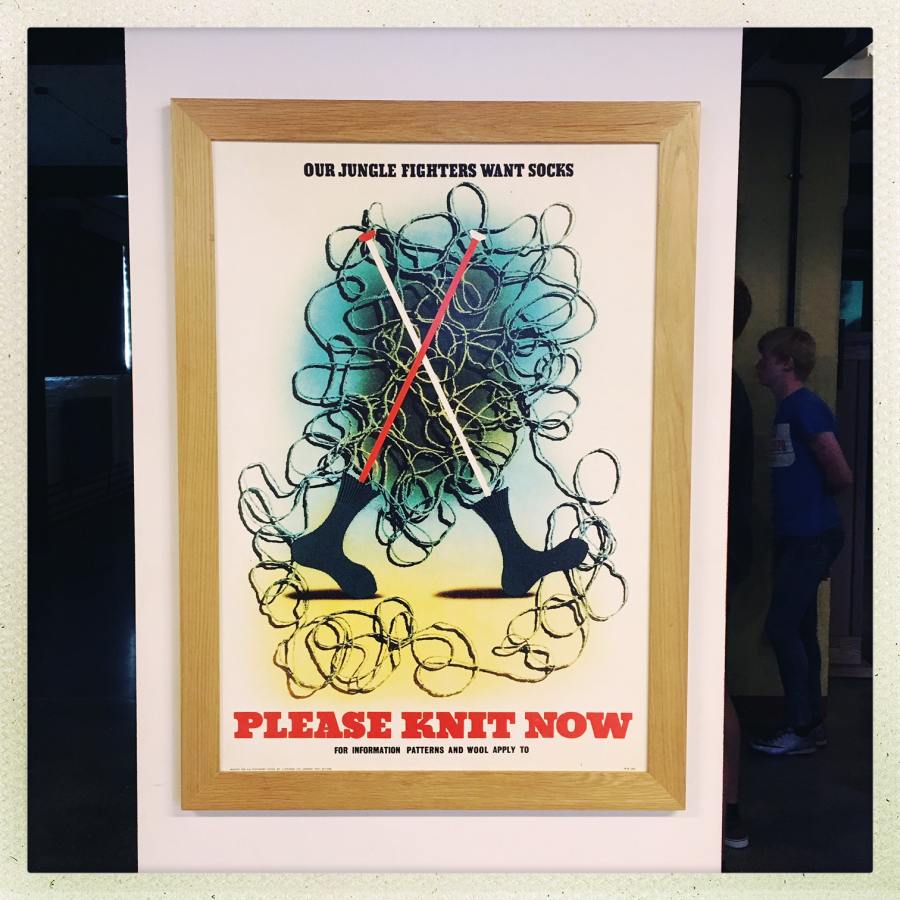

The poster of the “knitting needed” reminded me of a bit in a George MacDonald Fraser book (I am pretty sure it’s Quartered Safe Out Here, which is on my recommended reading list[stderr]) Apparently the “get the knitting out” campaign was good for morale but produced some truly terrible socks. Imagine some highlanders in Burma slogging about in the jungle in hand-knit socks that have irregular tension in the stitches. It’s exactly the sort of thing Fraser remembered and wrote about, vividly.

The site is breathtakingly quaint; there’s a pond with swans, a croquet field, bicycle racks, lawn chairs – and the main building is a Lovecraftian architectural horror that is so wrong it flips the dial around to “not so bad.” The museumy bits are a mix of “sons et lumieres” projected on walls and screens, consisting of interviews with people who worked there, and there are a lot of reconstructed spaces that do look like the codebreakers just left off what they were doing for a while.

Griffon sprains his eyes from rolling them too hard.

Griffon symbolized protecting something important. In this case, it was probably appropriate – ULTRA – the secret that the allies were reading the German Naval Enigma encryption system – actually did have a major impact on the war. And WWII was a close-enough run thing for the British that they can legitimately say that “every bit counts.”

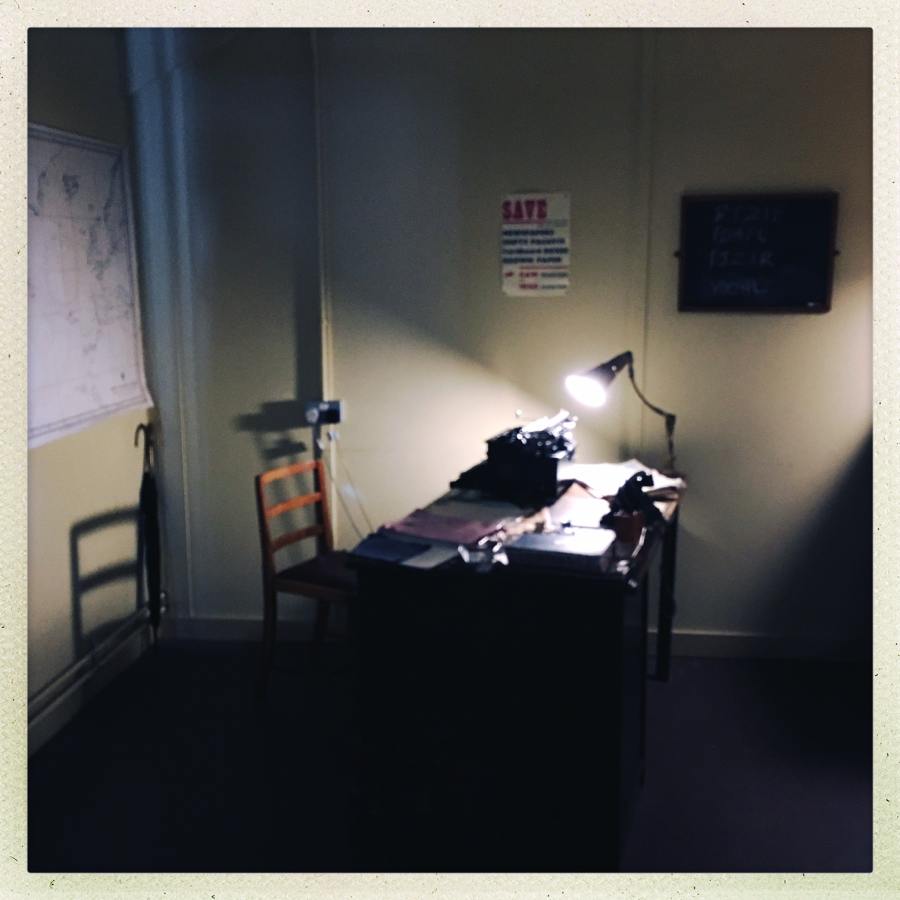

The main work was done in numbered huts – designed with blackout features: note the shrouded vents. Inside, they are very utilitarian:

It is an interesting fact of intelligence that the strangest places are where a lot of important action can happen. There are many huts at Bletchley Park, some of which were where the electro-mechanical code crackers were set up, others were rooms of teletypes, and others were where mathematicians (apparently the staff included 4 chess grandmasters at one time, which is pretty unusual!) stared at ciphertext and tried to think of new ways of compromising it.

There were women, too, of course, including women who worked on code-breaking. I didn’t see much about them, unfortunately (or I’d do a “hardcore of yore” posting about them), but it was a microcosm of civilization: cryptographers worked together, fell in love, got married, and cracked codes. One of the interviews I listened to was an old woman talking about how they often could crack some of the weaker German codes because cipher-clerks would use permutations of their girlfriends’ and wives’ names, as well as a variety of expletives. Apparently they once decoded a message from higher up saying “Stop using naughty words! Some of our cipher operators are young women and you will scandalize them!” Meanwhile young women in England were using swear-words of their own because it was very convenient for to decrypt messages where the keys were simple swear-words.

The memorial to the Polish cryptographers

I was pleased to see the memorial to the Polish cryptographers. As the war was bearing down on them, some mathematicians in Poland managed to make some helpful inroads into the German cipher machines, and figured out a few of the rotor architectures, but could not break past the key-initialization plugboard that altered the engine’s inner state when a message was begun. The Poles, uncharacteristically for military intelligence cryptographers, gave all their work to the British before it was too late for them to continue – a noble and important gesture.

Alan Turing’s desk

I was disappointed that the signs simply listed the date of Turing’s death and did not mention why, though I was pleased to see elsewhere in the museum was the posthumous pardon granted in 2013 by the queen.

Most of the huts were gloomy and dark, moodily lit with point lights and equipped with period furniture. It was not a posh place, but it probably was a relatively comfortable place to spend the war compared to many many others.

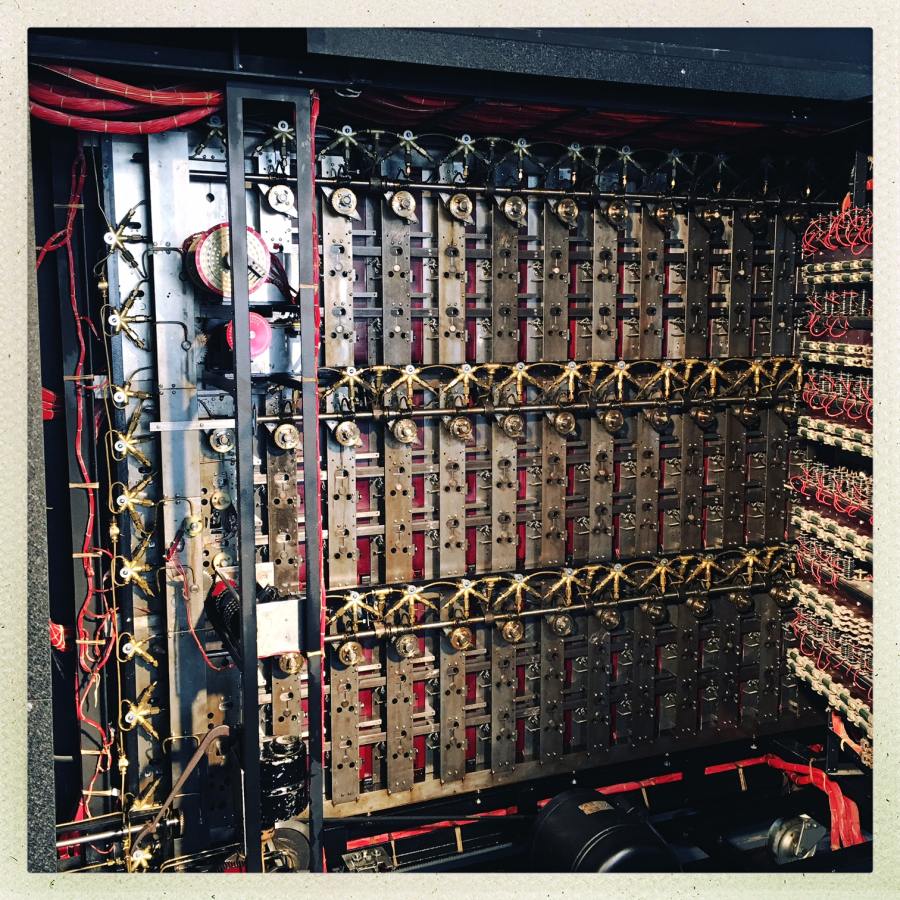

The heart of ULTRA is the device above; that’s the drive-plane of one of the “bombe” electro-mechanical decryption engines. The little curving brass pipes are a machine-oil distribution system that kept the gears lubricated; the bombes ran as fast as they could without falling apart: every extra RPM meant more cipher-setting combinations checked.

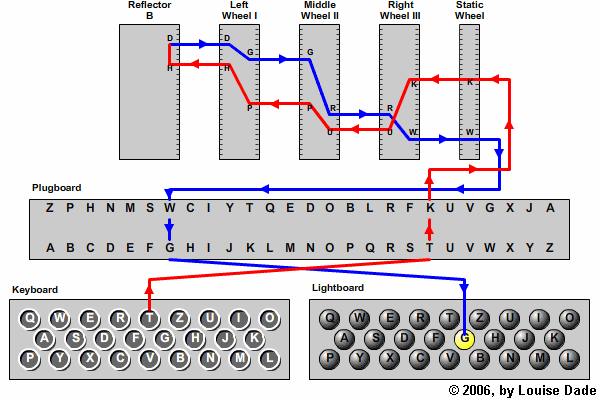

The mathematicians were able to only get so far against ENIGMA so they designed and had built a set of engines that could complete the decryption. The way an ENGIMA machine works, it encodes the messages using an electrical current that is carried through a set of rotors that move with clockwork drives every time you encode a letter. So, you push a key (once the rotors are started in the correct setting) and a letter lights up on a panel above the keyboard. When you push the key, the clockwork moves the rotors, which progresses the circuit.

I will do another posting about ENIGMA machines later; I have something beautiful and wonderful to show you about them.

[source]

There were a few other encryption machines in the museum, including a Japanese ‘tunny’ machine and some early rotor machines, but the bombe is the thing to see at Bletchley Park; it’s the signature device of early crpytanalysis. Later, an early digital computer called COLOSSUS was installed at Bletchley Park, but it was dismantled to save space – “COLOSSUS” was a good name; many early computers were rooms and rooms full of delicate wiring that would fail if you looked at it sideways.

I had a cup of coffee in the Hut 4 cafe then hiked back to the train station, to London, and took a taxi over to the Victoria and Albert to visit some old friends.

If you want to know how ENIGMA machines worked [how]

ENIGMA machines occasionally come up on Ebay. I think the last one went for about $30,000. You can buy replicas for relatively little. Right now (I just checked) there’s a Hagelin M-209 for $3,500 – which is a pretty high price for a fairly common machine. There’s a fun story about Hagelins: the NSA “helped” Hagelin with his encryption design. “Helped” a weakness right into it. They pulled the same trick on a company called Crypto AG – NSA shenanigans regarding weakening encryption are nothing new (which is why most of us major colonel lieutenant generals in the Tin Foil Hat Brigade tend to assume that anything coming from the NSA is double or triple-edged, and only the NSA knows the number and direction the edges are facing)

I found these videos put out by the Numberphile channel to be a good primer for how Enigma machines worked and were decoded, discussed by a mathematician.

A computer science professor on an associated sister channel has a related video, but I’m not sure what its angle is yet as I only just discovered it.

Reginald Selkirk@#2:

Yes, that’s a pretty amazing indictment of the technical skills on display at some government contractors.

Holms@#1:

The “computerphile” videos are excellent (I just watched them both) The explanations are very good – especially about the way you can crib known plaintexts with the non/mapping same character.

Carl Ellison, when I worked with him at TIS, did his own cryptanalysis of ENIGMA, but he knew I couldn’t follow it so he didn’t bother trying to explain it.

Now, if you want to see when cryptosystems got cool, look up feistel networks. They are a rotor architecture for computers and they made up most of the 1st generation computer cryptosystems such as DES. If you have been studying ENIGMA feistel networks may suddenly trigger a big “aha!”

The stuff the computerphile guy was talking about with regard statistics is where William Friedman came in with his “index of coincidence” – statistical analysis of conditional probabilities can tear apart rotor machines – that’s what COLOSSUS was for.

Apparently ENIGMA machines are fetching around $200k now!!

A nifty bit of history.

I remember reading a while back that while doing some sort of maintenance work on the huts — I think it might even have been Turing’s own — they found some papers with miscellaneous crypto notes folded up and wedged into the cracks, presumably to stop the wind from blowing in during the winter. Technically, an operations no-no, since all such scraps were supposed to be destroyed.

Owlmirror@#6:

they found some papers with miscellaneous crypto notes folded up and wedged into the cracks, presumably to stop the wind from blowing in during the winter.

That would be typical of “egghead” users, even in war-time.

Realistically it’s probably not that much of a threat. The security of Bletchley Park was mostly that it was obscure. Had the Germans known what it was, they wouldn’t have sent spies to recover bits of paper, they’d have bombed the place flat.

There are some indications that Donitz may have suspected the Naval ENIGMA was broken, but by that time, his options were limited and all he could do was rearrange the code wheels.

There’s a great book about ENIGMA cracking called Seizing the ENIGMA (Kahn) – it reads like a spy novel (it is!) – I won’t offer any spoilers, but the way that the British eventually captured a working German Naval ENIGMA was really hair-raising.

Interesting… I’m younger than you, and yet it really doesn’t seem that far off. I wonder if that’s more a result of the omnipresence of WWII in British culture, or the foreshortening effect of your living in a country with less history? I’ve often got the impression that Americans have a very foreshortened idea of history… I know people who’ve lived in buildings that are older than your country, and retained a lot of their original features, so we have a different perspective. The building I live in was built in 1894, and that’s not particularly old around here. On the other hand, WWII is everywhere…

Thanks for a fascinating peek at the Bletchley Park Museum! It’s definitely on my bucket list. Two things I’d like to add…

For the record, just last week an Enigma sold at Christie’s for $547,500. — admittedly, it was a 4-rotor naval model, which are extremely rare even among Enigmas, but still… Holy moly!

Also, I highly recommend the Bletchley Park Museum weekly podcast. It sounds like a really fun place to work!

The air conditioning system on a British bus rarely breaks down. When it does, just apply some oil to the hinges located at the base of the main panel and it should flip open again.

It’s cute you think any bus in the UK has ever been fitted with air conditioning.

I visited Bletchley a little over a decade ago. Two things stuck in my memory:

1. there were a bunch of chaps (not men – these were indisputably chaps) rebuilding Colossus. They were invariably sixties or older, white haired, pencils behind their ears and long brown coats on. They worked behind a velvet rope, and were ready to chat to anyone interested. I asked how they were getting on, and was stunned to find they had no plans to work from – all the plans had apparently been destroyed, something about them being, y’know, ultra top secret. They were working from memory and photographs. I asked who was funding the effort, assuming that this recreation of an item of international historical significance was being supported by IBM, or Microsoft, or even just the Heritage Lottery fund. The answer was “we are” – as in, the fellows behind the ropes were spending their retirement rebuilding the first ever digital computer for shits and giggles out of their own pockets and what they could scrounge off people like me. Not that they needed much – it transpired that much of the actual mechanics of the thing were based on old telephone exchange equipment, of precisely the sort that was, at the time, being disposed of in large amounts by British Telecom as they replaced the old mechanical systems with digital alternatives. I asked how much BT charged them for the scrapped exchange equipment. Apparently, BT refused, point blank, to sell them any. Insurance, liability, health and safety, blah blah blah, it just wasn’t for sale. Of course, if someone sympathetic to the cause knew which exchanges were being decommissioned on which days, they could tip you the wink and you could always just hang around by the skip… which was exactly what they did. It is, bar none, the most spectacularly geeky enterprise I have ever been privileged to witness first hand.

2. a tour guide told us that when they were setting up the museum they visited some of the people who had worked there 50 years earlier in order to hear their stories. At first, they encountered problems, as there seemed to be many administrative errors. Again and again they would turn up to some old lady or gentleman’s house and say “Our records show you worked at Bletchley Park in the war, we’re building a museum and would like your help telling the story”, and again and again they’d be met with polite but disappointed “Sorry, I don’t know what you’re talking about, I worked in an artillery factory/the pay corps/logistics planning/a farm/whatever”. Only after this had happened a number of times did they realise their records were correct, it was simply that these people had signed up to keep a secret, and fifty years on they were still keeping it – all of them. It took them some time and some official correspondence to break through the wall of denial and reassure these people that it was now, finally, OK for them to talk about what they did. One common debunking tactic when dealing with moon-landing deniers is to point out that a large, complex organisation simply couldn’t keep a big secret for decades – but that assertion is dead wrong. (Mind you, NASA is an order of magnitude bigger than Bletchley was, and Apollo generally probably another – but still…).

Sonof, bear in mind another difference in play when keeping secrets: Motivation. The Bletchley people were engaged in secretive work to overcome an existential threat, while NASA people are (alleged to be) working to decieve the public for some kind of con. Any principled employee would happily spill the beans in the latter case, whereas any principled employee in the former would be resolved to take it to the grave thanks to the dire circumstances surrounding that secret.

sonofrojblake@#11:

It’s cute you think any bus in the UK has ever been fitted with air conditioning.

Surely something has to move the pee-smelling air around. Relying on brownian motion is too slow!

I asked how they were getting on, and was stunned to find they had no plans to work from – all the plans had apparently been destroyed, something about them being, y’know, ultra top secret. They were working from memory and photographs.

Yup! Nuts, huh?

That sort of secrecy – as well as loss of skill – is one of the reasons why they aren’t making any more rocket motors like the ones that lifted Apollo: it appears there aren’t very many artists who can weld like that, anymore, and there are so many subtle side-effects in the design that aren’t understood and can’t be teased out observationally. I suspect the Colossus and bombes are similar – you know, that little pipe that makes that weird little curve? That’s to slow the oil down and if you leave the curve out then the oil squirts too far on the other end. That kind of thing. I’ve had a chance to examine one of the Saturn-5 engines at Michaud assembly area, and there appear to be a lot of similar side-effect engineering hacks. The bombe is also full of them – just look at the oiling system and you can see what I mean; it’s semi-gravity-fed, which means it was built for a specific viscosity of oil (probably whatever they had in the mess hall for all I know!)

Only after this had happened a number of times did they realise their records were correct, it was simply that these people had signed up to keep a secret, and fifty years on they were still keeping it – all of them.

Ok, now that is awesome.

“Oh dear me, you’re mistaken! I worked on a machine that printed greeting cards through the whole war!”

One common debunking tactic when dealing with moon-landing deniers is to point out that a large, complex organisation simply couldn’t keep a big secret for decades – but that assertion is dead wrong.

Yet, as soon as the war was over, the story began to leak. By now, if there were a lunar landing conspiracy, it would have begun to leak.

Odd you mention lunar landing conspiracies. I did some work on that a few years ago, which I never finished. I wonder if I could somehow use this blog as a way of pulling some of that content out of me. Hm.