This is the first in what will be a short series that I will try to drop over the course of the year. Because, I grew up reading National Geographic and it wasn’t until I was well into my adulthood that I discovered that I had been absorbing subtle doses of propaganda along with the cool stuff that excited and inspired me.

When I was a kid and visited my grandparents, one of the most amazing things about their house was that they had all the back issues of National Geographic. In sequence. It was a serious crime to put an issue back out of sequence, but I could take them, curl up someplace quiet, and read them. It was through National Geographic that I discovered breasts, rockets, scuba, mountain climbing, and other important things. (History came through a huge stack of Smithsonian) I hadn’t realized, at the time, how sanitized of geopolitics National Geographic was, but that’s probably because there was a great deal of fascinating other stuff to devour.

May 1961, page 720

I later met someone who worked in the National Geographic publications arm, who had worked on some of the big boxed book sets, and what they did was truly a labor of love. The articles in National Geographic were huge, well-written, and – mercifully – written for adults: they were interesting and educational and exciting.

There was a lot about the run-up to the space race and the moon landings, and it wasn’t too overtly propagandistic, though it downplayed (as usual for American media) what was going on elsewhere in the world. In fairness, in the 1960s, what was going on elsewhere in the world was pretty depressing: as usual the US was dropping high explosives and chemical agents on people. But the space program was a shining beacon of sciency goodness for a kid like me. I marvelled at the piloting skill needed to catch a Discoverer satellite returning to Earth!

Discoverer X, the recovery of man’s first object shot into space, came – um…. Well, Laika the dog was shot into space in 1957, and before Discoverer X was Discoverer I, etc. So that seems like a bit of gratuitous though minor propaganda.

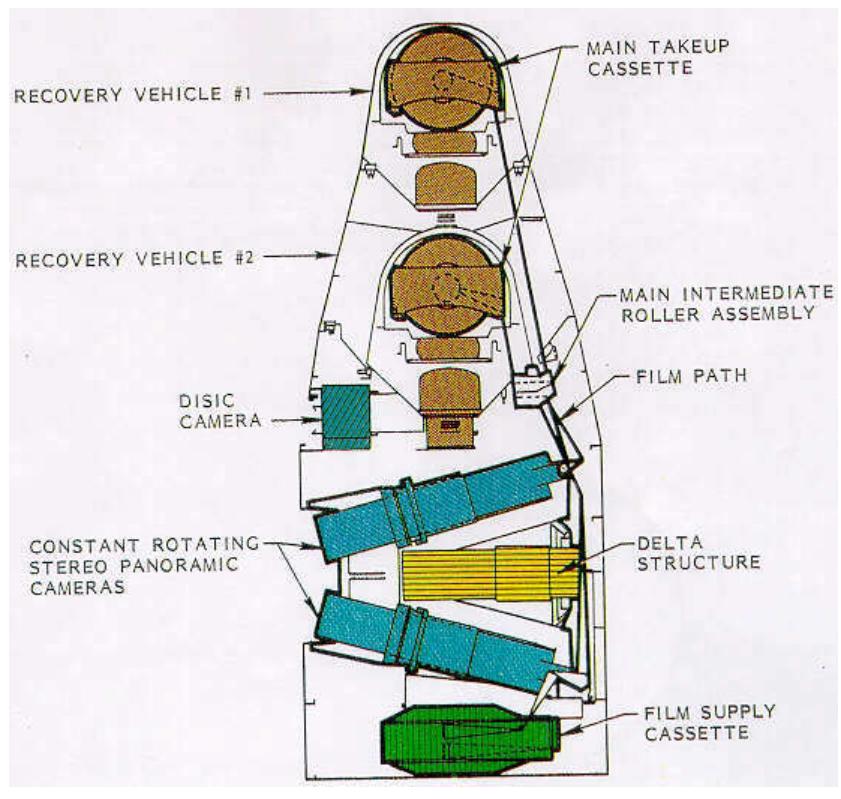

The National Geographic article is sort of a hodge-podge of spacey stuff, including pictures of Ham the chimpanzee, who also was launched into space (January, 1961) – the descriptions are all pretty sciencey. Discoverer, for example, is described as: “carried devices to gather data about space.”

It was a spy satellite.

Mis Shmidta Airfield, August 1960 – first successful satellite surveillance photo. Source: National Reconaissance Office [nro]

You can probably imagine my surprise when I read Curtis Peebles’ The CORONA Project – America’s First Spy Satellites [amazon]and recognized the pictures of the cameras being snagged on re-entry by the planes. I also read Dwayne Day’s Eye in The Sky [amazon]

Back in 1994 I taught a class at Kodak up in Rochester, NY, on UNIX system performance analysis and tuning (yeah, exciting!) and had a great time chatting with some of the technical people there. Even in 1994, Kodak was an ultra-dense collection of very smart technical people. When they learned that I was a bit of an amateur photographer, I got a tour around some of the research labs (amazing!) and had lunch with the people who had developed T-Max tabular grain film. They were an interesting mix of practical and theoretical – comfortable with trying to figure out how to optimize sensitivity of film grains at different wavelengths using quantum mechanics, and “just trying a lot of options.” They were happy that I was a fan of the T-Max emulsion, and when I said that I also used a lot of Technical Pan film – only, developed in Agfa Rodinal instead of Technidol (which was labelled on the bottle as “teratogenic”) one of the old guys shook his head, “that stuff really doesn’t work with anything but Technidol” It turns out he was involved in the design of that film, as well. He told me a story about how people came from California and were very “sekrit skwirrel” about that they wanted a very very very fine grain film that was balanced toward the infrared. So the people from Kodak made the film and sent it to the guys from California who said, “you can leave the anti-halation layer off, we don’t need it. And can you make it on a thinner base?” At that point, I started to laugh. Anti-halation layers are dyes in the film base that keeps light from diffusing through the film-base itself, it’s only a problem is your light is being diffused by atmosphere. I hadn’t heard about CORONA yet but I knew spy satellites existed. The guy went on, “after months they came back with a box full of crumbly powder that used to be our film. They said, ‘… and it has to be able to withstand very cold temperatures’ and I replied, ‘Yeah, and let me guess, it also has to withstand really hot temperatures.'” At the time, I didn’t understand what he was saying, but it made sense when I learned about CORONA years later. A very thin (irritating as hell to get onto a reel) polyester base called ‘Estar’ was unique to the film; I knew Technical Pan film must have been made for spy satellites, but it never occurred to me that they were dropping film from orbit.

The fourteenth CORONA mission was launched a week later [after Aug 10, 1960] and, after seventeen passes over the USSR, returned 16 pounds of film. This mission produced a cornucopia of data and gave more coverage of the USSR than all prior U-2 flights combined. For policymakers and intelligence analysts alike, it was as if an enormous floodlight had been turned on in a darkened warehouse.

CORONA photography quickly assumed the decisive role that the Enigma intercepts had in World War II. When the American government eventually reveals the full range of the reconnaissance systems developed by this nation, the public will learn of space achievements every bit as impressive as the Apollo moon landings. One program proceeded in utmost secrecy, the other on national television. One steadied the resolve of the American public; the other steadied the resolve of American presidents.

National Geographic helped give a bit of top-cover to several significant espionage operations. Maybe they were lied to. Maybe I was lied to. It’s not a huge lie; I don’t really care. What I do care about is that, thanks to CORONA, the US President knew that the “bomber gap” and “missile gap” were errors. But it was convenient to let the people believe there was a good reason for a massive defense build-out. It was CORONA intelligence that encouraged the US to station medium range missiles in Turkey (knowing exactly where to target them) and it was CORONA intelligence that spotted missile bases being built in Cuba, long before President Kennedy made a big, dramatic, counter-move, taking the world to the brink of a nuclear war that – thanks to CORONA – the US was pretty sure it could win, but it didn’t want to risk paying the cost of a few cities.

Slowly, over years of learning about the intelligence community and some of the things it has done, I came to conclude that one of the greatest dangers to humanity is differential knowledge. If one side thinks they know something that the other doesn’t, they may think it’s safer to start a war. And, they will. Because, in general, we persist in putting the power-hungry and egomaniacal in positions of authority over great and terrible war-making forces.

By the way, for a low price – under $30 – you can have access to all of National Geographic back issues. Get the digital/paper membership and you can read them until your eyes bleed with joy, just like I did when I was a kid. Awwww, who am I fooling? When I read this stuff I am a kid again. PS – it’s searchable – otherwise I’d have had to re-read the whole thing in order to do this article for you, which would have bothered me not a whole lot except for the part where I vanished for a month. This is the article, in case you want to find it: [natgeo]

Edwin ‘Din’ Land, the inventor of the Polaroid Camera, was a consultant on the optical systems of the CORONA, as well as on the film (predictably, Land initially wanted the satellite to develop the film in space) Many of my early technical heroes such as Harold ‘Doc’ Edgerton were involved in a lot of sekrit skwirrel stuff during the cold war and before. All those early photos of nuclear explosions? Doc did them.

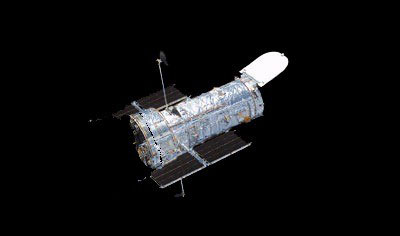

The CORONA satellites were known as KEYHOLE 1-5. KEYHOLE became the name for the US’ line of spy satellites, up to the KH-11/Kennen, which (if you look at a picture of it, and the Hubble Space Telescope – they’re Arkansas cousins [similar]) was partly responsible for the invention of digital photography. The current generation of spy satellites are no doubt impressive but appear to have become so expensive and complicated that there aren’t very many of them – a typical trend in American systems procurement.

The CORONA books have some pretty cool pictures in them, including one of my favorites, which is the pieces of a CORONA that were returned to Lockheed after a failed launch. “Here’s your satellite.”

One of these is a KH-11, the other is the Hubble Space Telescope. Or should I say: Both of these are KH-11s, one points up one points down and has a shorter focal depth.

Off-topic: Putin caught in stone cold lie

And Oliver Stone bought it.

Now that they have electronic sensors instead of film, they last longer and “dropping packets” has a completely different meaning. If they last for years or decades, how many of them do you need?

I recently discovered that a local library system provides free access to the NatGeo archives. I went looking for an article I remembered reading quite a few years ago, by Chris Hitchens (I was reminded of it by your recent post about the current situation of the Kurds in the current Middle Eastern conflict)

Hitchens, Christopher, and Ed Kashi. “Struggle of the Kurds.” National Geographic Magazine, Aug. 1992, p. [32]+. National Geographic Virtual Library

Incidentally:

Is that where you picked up the phrase “secret squirrel”, or was it floating around before that time?

Reginald Selkirk@#2:

Now that they have electronic sensors instead of film, they last longer and “dropping packets” has a completely different meaning. If they last for years or decades, how many of them do you need?

More than one. It’s unknown what they’ve got up there now, but none of us should be comfortable with the idea that the US might suddenly be blind in addition to being stupid.

Security around spy satellites is generally very good (though the “Falcon and the Snowman” spy case appears to have involved the leak of KH-11 plans) What we do know about the state of the art is pretty limited. Apparently the new Advanced Imaging Platform was frontloaded in procurement by Lockheed and it experienced 700% time overruns and at least 300% cost overruns. It also appears that one of the spy satellites was blown up on launch in 1998. There was another that blew up on 2006 and was described as “multi-billion dollar” (apparently around $3bn)

There is a pretty impressive list on [wikipedia] but I can’t vouch for it. There are a lot of people whose hobby is watching the spy birds go up, and they’re generally pretty good at identifying the satellites and launches but the specs of the satellites are closely held. Maybe Trump will tweet the specs out to us if we troll him hard enough.

By the way, in researching this, I wound up searching up a bunch of the latest stuff about spy satellites. I had never heard of the NOSS/Intruder satellites before – they’re pretty brilliant – basically, it’s a reverse GPS: if you have geostationary satellites listening to ship communications, you can locate the signal very accurately using differential arrival time. Neat!

Rhyolites are another older spy satellite that are beginning to become declassified – also very clever: position the satellite geosynchronously so that it catches the spill between microwave communications towers, thanks to the curvature of the Earth.

Owlmirror@#4:

Is that where you picked up the phrase “secret squirrel”, or was it floating around before that time?

Secret Squirrel was a cartoon character in the 1960s when I was a kid. I didn’t watch much TV but I love trenchcoats.

Hitchens, Christopher, and Ed Kashi. “Struggle of the Kurds.”

I’ll read it!

Reginald Selkirk@#1:

Putin caught in stone cold lie

It’s possible that someone is going to have a very very bad day for embarrassing Vlad I like that. It may have been some basic propaganda that nobody ever expected Putin would push. Whups! Either that or he was trolling Stone.

It’s also possible that they’ve gotten better at piggy-backing the spy stuff into civilian applications… Commercial imaging’s so good now that you probably don’t need as much dedicated top-sekrit shit.

Dunc@#9:

Commercial imaging’s so good now that you probably don’t need as much dedicated top-sekrit shit.

I doubt they use that, much. If they suddenly asked Landsat to swing a few loop over South Wherever, that’d be giving away a bit too much. Besides, the intelligence community has, basically, infinite money.

The biggest problem, fairly consistently, has been keeping NSA, CIA, and DoD from duplicating efforts. To prevent that, the National Reconaissance Organization (NRO) was formed, to own satellite programs. And the CIA promptly spun up its own satellite program, anyway.

The commercial market had enough coverage that you normally wouldn’t need to ask anybody to reposition anything. Certainly, all the market analysis I can find (without paying for it) indicates that the defense and intelligence sectors are big customers.

Sure, they’re always going to want their own assets for specialist applications, but you can do a hell of a lot with what’s commercially available, if you apply the right processing and analysis.

Dunc@#11:

Yeah, no doubt: for regular flyover stuff like analyzing to see who’s building bases where – commercial is fine for that. I also know for a fact that google maps is used by a lot of intelligence services, because any searches through there are lost in the noise.

I believe they are using a lot of tactical satellite, too, and that’s all going to be private assets. There are some interesting tidbits in Bowden’s Black Hawk Down about the level of battlefield telemetry that the military expects nowadays.

Re: Reginald Selkirk (#2):

You can still make a case for launching lots of them – especially, I imagine, if it’s paid for by the Pentagon with its apparent mission to spend every US dollar in existence on “defence”. With more satellites you get an updated picture of the entire planet more quickly. It also means faster response times if someone wants to look at a specific location right this minute.

In fact, the way trends are going these days, if a civilian or commercial entity wanted to tackle the same problem they’d probaly choose a swarm of cubesat or something similar.* They’re small, cheap and easy to replace if something goes awry. The only downside is the lack of room for large or powerhungry equipment, which might be a problem for the military. Then again, this sort of problem is the very reason why the space sector can get so creative trying to fit better systems into smaller spaces. Big satellites are becoming less popular because they require bigger launch vehicles, are just as vulnerable as small satellites (and a bigger target – and source – for debris). And even for satellites they tend to be hideously expensive.

I have no idea where the military might be headed, though, but it would be interesting to know what they’re doing. I suppose since money is no object, they can stick to clunky designs stuffed to the bursting point with the latest tech. On the other hand, swarms should be attractive because they’re much harder to disrupt. You can shoot a big satellite down, but in the case of cubesats you’d have to bring down a lot of them in order to make a dent in a global network. Your opponent, meanwhile, could just shrug and stick a few replacements on the next commercial rocket with some spare payload capacity.

*That, or the economical, sensible, practical and, above all, boring version: Let’s build just one satellite and wait a while.

“Liechtenstein has the best spysats of them all. Leaves US rubbish in the dust! Also has the greatest secret spaceport in the world (gold and royal statues everywhere!). Makes KSC look like a run-down dump. #MLGS” (Make Liechtenstein Greater Still)

That, plus a news story about Liechtenstein’s latest clandestine satellite launch planted on FOX news, should give you the desired results. Liechtenstein would deny everything, of course, just as you’d expect. If anything this would prove the story was true all along!

@komarov #13: Disrupting a swarm would be more of a cyberwar thing. Taking them out physically would be useful because you could use it as an excuse to develop tech to clear out debris from orbit but it’d probably be more practical to attack the communications channel. Add a bunch of noise to degrate it’s usefulness if you must or outright own them if you can.

For that matter, I wonder how much of that is going on with the single big type of satellite.

Cold war doctrine says that if you lose more than one spy satellite in a brief period you immediately go to DEFCON 1. The assumption is that you’ve been blinded because the enemy’s silo doors are rolling back. If someone took a bunch of US satellites offline as part of a cyberwar, they’d better be prepared to win the full up nuclear exchange that would follow. Of course, given the US’ prediliction for low quality attribution, that might amount to “we nuked Germany because the IP address of the server that the phishing attack was launched from was German” [By the way, that’s why I am so hyper-cautious about attribution. Some day, some poor bastard is going to get killed for having the wrong IP address, and most of their neighbors and their family.]

That’s why, generally, satellites have been treated as untouchable, and that’s why there was a lot of hue and cry when the US shot down USA-193 with a sea-launched missile. That was a demonstration intended to scare people, but there was a good fig-leaf, that its orbit was decaying and it was going to land on a populated area.

… Forgot longstanding doctrine: Blame others for your incompetence at every turn. I stand corrected.

I was a scientist at Kodak Labs when you visited, but unfortunately we didn’t meet. Admittedly, I was one of the lesser lights in a veritable galaxy of superstars working there. I’m not a film specialist, but I wanted to chime in with another point about antihalation. The main job of this material is to prevent unwanted exposure of the emulsion from light reflected off or waveguided in the filmbase. Without this layer, stray light near bright regions of an image can create a false adjacent “halo” in the photograph. Another possible reason for omitting the antihalation from the spy film might be that all the images were essentially low brightness, low contrast. No bright features –> no halos.

Re: lanir

I agree, actually destroying a group of cubesats would not be the easiest approach. The mentality does present two “advantages” though: First, you can spend tons of cash on the arsenal you need to do it. Second, when you do it, it’ll be a greaat photo-op, at least if Trump’s attack on Syria is any guide. Granted, you probably have to be in a senior military role before you can appreciate those advantages. Civilians might ask silly questions such as ‘why’ and ‘how much?!”, bless their naive little hearts.

Re: Marcus Ranum:

(As usual) I had no idea and (as usual) ignorance is bliss. But that does raise the question what kind of damage you could do to another country’s satellite infrastructure before they decide they’ve had enough and go for the nuclear option. There are plenty of targets, after all:

If the goal was to cause economic (and general) chaos meteorological satellites might be a good target. Weather forecasting is important but probably not something a country would risk a nuclear exchange over.

Targeting commercial communications satellites would probably be pointless – there are too many of them to do real damage to anyone except to the companies owning and using them. So, unlikely, unless the people involved in the attacking government also happened to own stock in telecomms companies. The affected nations would probably stick with strong words – unless their politicians were shareholders, too.

I’ll just assume that all the big militaries – those that worry about doomsday and how to implement it – have plans to smash everyone else’s version of GPS. That’s probably a bit trickier and not helped by more independent networks being set up. Once again prudence is getting in the way of total destruction.

And finally, if the goal was to be as obnoxious as possible, how about shooting down some prominent scientific satellites? Nothing says “I don’t believe in climate change” like downing a couple of Earth Observation satellites.

However, any such show of force, whether it was done for propaganda purposes, out of spite or had some other goal, could become very embarrassing very quickly if it accidentally triggered an ablation cascade, wiping out everything. “Oh dear, that went a bit further than we’d intended. Sorry?” That might even include the ISS. Although I find it disturbingly easy to imagine that there are some people with power somewhere, who’d love to go down is history as the first people to destroy a manned space station.