I’m a moral nihilist, which is not to say that I kick puppies and punch grandmothers – it’s just because I am unconvinced by the attempts to establish systems of ethics that I’ve encountered, so far. I’m a fan of “the golden rule”, i.e:

“That which you hate to be done to you, do not do to another.”

In action a rule like that should probably be more tightly specified, maybe resembling:

Before you do something that affects someone else, consider how you’d feel about someone doing it to you.

That way, you’re establishing your rules-base efficiently – your rules only need to apply to choices you only actually encounter, and they do twice as much work. If I am thinking about how much I’d love to smear peanut butter in Tucker Carlson’s hair, I assess whether I’d be willing to have random strangers do that to me, and now I have a rule that works for me, Tucker Carlson, and random strangers. By the way, this gets me around having to take “trolley car” problems and hypotheticals seriously, because I can say, “I don’t know because I’m not actually in that situation.” Then the test-giver asks, “Yes, but imagine if you were!” and I can helpfully reply, “I can tell you that it annoys me to be asked this question, and I wouldn’t ask you such stupid hypothetical questions. Can we agree not to annoy each other?” One concern that arises from this is the degree to which situations are contextual, how specific the rule is: is it OK to do the peanut butter thing on Tucker Carlson, but not on Carl Sagan? That’s tricky, so I apply two other rules:

The conclusion of ethical reasoning should be as de-contextualized as possible.

The conclusions of ethical reasoning should be as broadly applicable as possible.

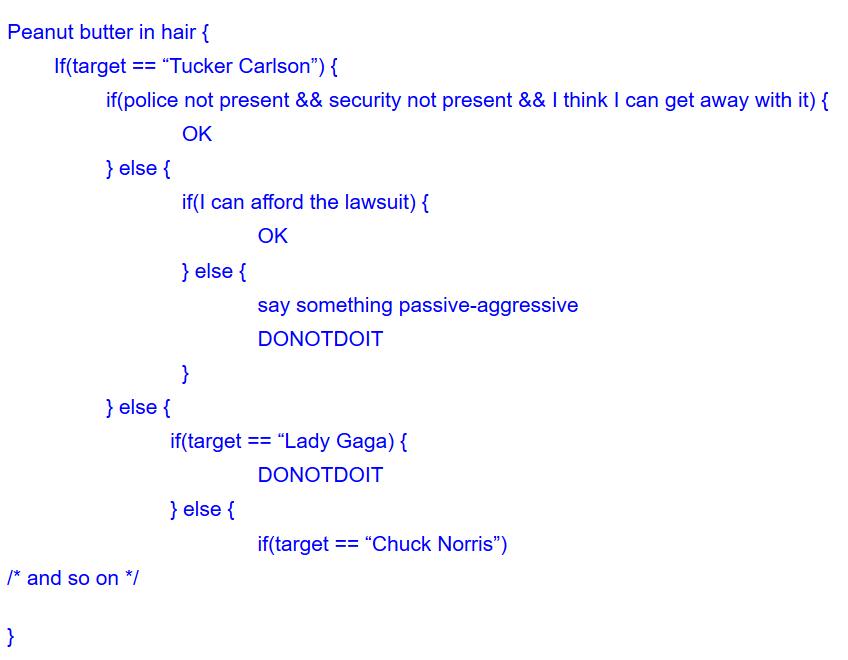

This makes conclusions (the rules generated) as useful as possible and saves me the trouble of having a bunch of rules that are a huge cascading chain of “if” statements.

My sample rule above got a lot more complicated because I was adding a lot of exceptional cases. The fiddly code around police presence and lawsuits are an example of the additional rules that come in when we make our rules context-sensitive. Keeping it simple makes it easier. It also makes it easier to communicate with others because you can tell someone “don’t do that” and you don’t look like you’re the kind of cowardly creep who’d put peanut butter in a wimp like Tucker Carlson’s hair, but you’re scared of Chuck Norris. (That then invokes a “do I care what people think about my courage?” question, which results in another rule being developed or reinforced)

The reason you want to establish your ethical rules before they’re invoked is because, rather obviously, you might smear peanut butter in Chuck Norris’ hair and find out later that Chuck Norris can punch pretty hard. The ordering “think, then act” is probably a key hallmark of “intelligence” (whatever that is) because it entails quickly building a temporary model of how the future may play out – the accuracy of that simulation determines our ability to predict the future. If my future model isn’t very good, I might predict that Chuck Norris will be amused if I do the peanut butter hair thing, and I could make a life-changing mistake.

If you’re still with me, I’ve already argued that de-contextualizing the rules makes them more efficient by making them less complex. One of the crucial contexts that I didn’t mention is: time. A pretty efficient rule is “Chuck Norris never likes peanut butter in his hair” and an even simpler, more efficient rule is “Nobody likes peanut butter in their hair.” Although if I’m a secret peanut butter hair fetishist I might have an exception like “Generally nobody likes peanut butter in their hair but if you can figure out a tactful way to ask and they seem to like the idea, then go for it!” And that’s how we deal with consent and signalling: we add another layer of interaction into our model of the imaginary future. So I imagine Lady Gaga’s eyes shining like stars reflected in pools of rainwater when I ask about the peanut butter and she huskily whispers, “yes… how did you know?” and I ask her, “chunky or smooth?” and she says “chunky” and I like smooth.

Moral nihilist that I am, I not only am unconvinced by philosophers’ attempts to construct moral systems, I am skeptical about other people’s claims regarding their own moral systems. In the model I describe above, you can see that someone’s rules can be arbitrarily complex; there can be an ‘if ( )’ statement that they didn’t tell me about. In fact I assume that there are always an infinity of ‘if ( )’ statements that other people aren’t even aware of, because they do like I do, and they build their rules on the fly when they actually encounter a situation and have to deal with it. Then there are people I consider “inconsistent” who forget their derived rules and don’t try to be context-independent: they’ll do whatever they want in a situation and claim that the details of the situation warrant it. That makes them harder for me to model in my imaginary future universe, so I am uncomfortable around them because they are unpredictable and therefore dangerous.

All of this diversion is because I was fascinated by some of the Democrats’ reaction to the Republicans passing the Trumpcare draft. Apparently a few of them sang “na na na na, na na na na, hey hey, goodbye!” at the Republicans (implying that they’re going to lose the midterm elections and their jobs along with it) but the reason they did it is because some other Republicans did the same thing to some other Democrats years ago. Therefore, they were doing second-hand retaliation against a secondary party. [washington post]

The CNN caption for their article about it was “thirty one seconds .. that show why people hate politics” [cnn]. The CNN title is wrong: it’s 31 seconds that show why rational people doubt that politicians have any morals at all. This sort of thing demonstrates the extreme ethical inconsistency that results from bending your views to meet a partisan agenda. (The rule for that looks like: “if my party is wrong, OK. if my party is right, OK.” And if you ask some of them they’ll tell you they are moral people who got their rules from god or whatever.

That’s what I mean by “inconsistent” ethical systems: if it hurt the earlier Democrats’ feelings, then the earlier Republicans were a bunch of assholes. So the later Democrats were being a bunch of assholes – perhaps worse, because they were retaliating on behalf of someone else, using methods that they apparently had already established were the methods of assholery. Or they reverse-established that it was OK all along for those earlier Republicans to mock those earlier Democrats; that’s why my concern for time-as-context in ethical systems comes forward.

There’s another rule that gets translated as “two wrongs don’t make a right” which translates into my mind as “in order to do something to someone else that would hurt you if they did it to you, you have to add a lot of exceptions to your rules, thereby increasing your own rules’ complexity tremendously.” In my mind, that equates to inviting an eventual breakdown in which your rules become so complicated that you blow them away with a sulphurous blast of air from hell and adopt the rule most politicians seem to follow:

Do as thou will’t shall be the whole of the law.

Yes, I know I used a variant spelling from what Crowley used, which is probably uncool since it’s Crowley’s dictum in the first place. I make an exception by allowing myself to do that, because I want to: checkmate Aliester.

Before anyone worries that I take Crowley seriously: don’t fear for Marcus. I know he was a complete bullshit artist, a victorian Deepak Chopra who used goofy mysteriousness and deepities to get a lot of sex and drugs. Chopra has a lot of Jaguars, so I tend to appreciate Crowley more. He was a colorful conman and, given the current politics, I would have preferred to see him as president. At least he was articulate. [ac2012]

This posting is a long rambling roundabout argument for why “sauce for the goose” works as an ethical rule for this particular moral nihilist: it’s easy to flip a rule around. If you do that, you only need half as many rules! WIN! “Exceptionalism” is complexity, unless you do like Trump does and collapse it all down to “whatever I say is the whole of the law.”

Note: I do not actually fantasize about putting peanut butter in Lady Gaga’s hair. Sometimes when you’re searching for an example, you come up with a bad one. And, Chuck? We’re good. Right?

I generally tend to agree with the broad outline of the argument you’re making here, but… Is complexity necessarily a bad thing in ethical systems?. I’m not convinced that it is, because the world is complicated. Parsimony is a good thing in physics, but that doesn’t automatically mean it’s also a good thing in ethics, and it seems to me that the desire to boil ethics down to simple rules is a popular route to some very bad ideas.

Dunc@#1:

Is complexity necessarily a bad thing in ethical systems?

I’d say only in terms of processing power and ability to remember it. At a certain point, since these are all rules we’re holding in our heads, we’re going to have trouble holding them, and then we become unpredictable. In that case I would say we’ve become unpredictable because we have a broken ethical system (broken in the sense of: “I forgot big chunks of it”, which seems to be how some people behave…)

If I actually encounter the trolley car situation, I’d like to be able to figure out what I think is the right thing to do, so I have time to throw Sam Harris in front of the train.

True, the earlier Republicans were a bunch of assholes. However, the Republican Party is in some sort of weird positive feedback loop so that it is getting monotically more asshole-ish all the time.

As for ethical systems, none proposed are without criticism. I think the basic problem is that ethics were not systematically worked out from a central theory, but developed organically and empirically over the course of our evolution. Therefore it is perfectly natural that human ethics are inconsistent, and all attempts to pin them down with some underlying theory will probably fail.

Sorry, I’m a little light on philosophy, both in general and, in this case, because I’m still reeling that the singing actually happened. Reading it I assumed it was an odd analogy, aphorism or whatever you you were using. It’s a good thing you provided video evidence to the contrary. Wow.

Apart from the stupid childishness of it, there is also the staggering lack of humility. Remind me again, who was never going to win the presidency, according to the Democrats? And which party then got the White House and all the majorities? And here the political choir is gleefully predicting and taunting their enemies for their future election losses. Well, good luck. With their track-record they’ll need it.

—

On the philosophical side, my phrase of choice always was, ‘turnabout is fair play!’ Fortunately, I only ever apply it as the golden rule. If I horrid things to people, I can hardly complain about people doing horrid things to me, which I wouldn’t like very much at all. Thus one strives to avoid horrid things. If I had gone with the literal interpretation of turnabout I’d apparently be overqualified for US politics.

One of my earlier memories is having the “Golden Rule” explained to me after I punched my older brother. (I don’t know why he didn’t just punch me back.) With the logic of children, I immediately concluded that this was great — any time I felt like punching someone, all I had to do was punch myself with the same degree of force first, and I was in the clear.

This still feels like a flaw in the ethical system.

Well, if people actually based their ethical decisions on formal rulesets which could be diagrammed as flowcharts then that would be a problem, but since they don’t (and I have trouble believing that you think they do) then it’s not really relevant. The reality is that almost everybody’s (*) ethical system is a loose assemblage of differently-weighted heuristics, mostly involving things like social standing, in-group / out-group status, and system justification, and all formal ethical systems are just exercises in rationalisation which attempt to work backwards to derive some system of rules which produces the “right” outcomes. They are to actual human ethics roughly what RPG combat systems are to real combat.

* There are some exceptions, but those people are generally (and usually correctly) regarded as freaks and monsters.

I’ve always used the term ‘golden rule’ for the positive formulation, and the term ‘silver rule’ for the negative — the one you provided.

One formulation is prescriptive, the other proscriptive. Subtly different.

(Then there’s the LaVeyan Satanic formulation: “Do unto others as they do unto you” ;) )

—

I’m more of a moral pragmatist.

Ethical principles, ethical heuristics, no worries. Consideration for others, sure.

Ethical (deontological) rules? Problematic.

Reginald @4,

Indeed. People differ, cultures differ. Whyever would they share the same ethics?

—

brucegee @6,

You punching yourself is not the same situation as that person punching you; the actual situation would be that person punching themself and then punching you.

The actual flaw is that, if you happen to enjoy being punched (fight club!), then you can morally-justifiably go around punching people and feel virtuous about it.

(Thus why I prefer the ‘silver’ version — that I might like being punched is not the same thing as me disliking not being punched)

Dunc @7,

Ahem.

It’s relevant to institutions and collectives, if not to individuals. Political parties, for example.

Applied ethics is a big field.

I don’t think that Trolleyology (yes, they actually call it that) is all that bad. At least it gets people thinking about ethical dilemmas.

Paradoxically, this is a good time to be a Democrat congressman — a nice salary, little responsibility, and the Republicans are so depraved that almost anyone looks good in comparison.

John Morales @10:

Institutions and collectives have formal policies for this sort of thing (or at least, they bloody well ought to), and so don’t have to rely on individuals being able to hold all the rules in their heads.

But imagine Tucker Carlson’s “eyes shining like stars reflected in pools of rainwater” as you rub peanut butter into his hair.

How is the obnoxious singing by politician of either party morally inconsistent? Was there a supposition that any of them are above taking a vindictive pot-shot?

The Trolley Problem is a bit like the Prisoner’s Dilemma— it’s a distilled a purified version of a type of problem that comes up in real life all the time.

Anyone who dismisses it as an absurd hypothetical with no bearing on ethics in the real world clearly doesn’t know enough about ethics to be worth listening to.

“I don’t know because I’m not actually in that situation.”

“I can tell you that it annoys me to be asked this question, and I wouldn’t ask you such stupid hypothetical questions. Can we agree not to annoy each other?”

You can have ethical rules established before they’re invoked or you can have a moral system in which hypothetical scenarios are meaningless. You can’t have both.

Including the one you just constructed?

If I read and recall your post correctly, when you encountered the trolley problem last November, you chose to flip the switch and kill the one person to save the ten.

Well, there’s always complications that come up.

What happens if I decide to put peanut butter in your hair?

And if you think you can physically fend me off, what happens if a very strong person decides to put peanut butter in your hair?

Jessie Harban@#14:

Anyone who dismisses it as an absurd hypothetical with no bearing on ethics in the real world clearly doesn’t know enough about ethics to be worth listening to.

Way to miss the entire point! I’m not dismissing it as having no bearing on ethics in the real world, I’m saying that I don’t have to worry about trolley-style problems until I encounter them, at which point they are no longer hypotheticals and I’ll be able to make a decision based on the situation as I perceive it at the time. I actually have had to make a “trolley car” style decision in real life and I did it fast enough that there was no problem other than that I was nearly killed or mangled.

The problem with trolley car problems is that they fail exactly because they are “distilled” – they’re distilled to the point where the philosopher is expecting someone to commit to always act a certain way in a radically simplified situation. In reality, we encounter a situation and it doesn’t bear any resemblance to the stupid trolley car problem, except on some abstract level where we can post-hoc rationalize to our hearts’ content.

Your attempted well-poisoning attack “doesn’t know enough about ethics to be worth listening to” is interesting when you’re commenting on a statement from a self-described moral nihilist. I absolutely agree that I know nothing about ethics. I’m presenting some things about how I think about this stuff for my own purposes, I’m not trying to lay out a methodology or an ethical system for you. You’re welcome do to whatever you please and listen to whoever you want. But, if you don’t think I’m worth listening to, maybe you should consider me not worth commenting on, either?

You can have ethical rules established before they’re invoked or you can have a moral system in which hypothetical scenarios are meaningless. You can’t have both.

I see your assertion but I don’t agree. The reason is because hypothetical situations are always simplified from reality, so you can think a bit about what you might do in a certain situation (rules established…) that will predispose you to certain actions in the event you encounter a complex situation.

I think of it as similar to how race car drivers mentally review a course and hypothesize different things that could go wrong at different places, visualize it, and try to “pre-load” responses. Of course the actual situation will be different and often very different, but maybe you’re not going to have time to get into your armchair and smoke a pipe and think things through.

Including the one you just constructed?

I said “I am skeptical of other people’s claims regarding their own moral systems.” That’s not relevant to my own opinions about my own ethics. I’m quite comfortable doing what I do, when I do it. I have certain values that are likely to be expressed when I act, but it’s not imperative on me that you or anyone else understand them. Partly that’s because I’m confident that I can explain my reasons for my actions to someone else, if I have to, without resorting to explaining a complete constructive moral system to do it. (“Well, it started with the Big Bang…”)

If I read and recall your post correctly, when you encountered the trolley problem last November, you chose to flip the switch and kill the one person to save the ten.

Yeah, I’d probably do that every time.

What happens if I decide to put peanut butter in your hair?

Unless you asked first, I’d probably break your nose, at a minimum.

what happens if a very strong person decides to put peanut butter in your hair?

Am I armed?

ld7412@#13:

How is the obnoxious singing by politician of either party morally inconsistent? Was there a supposition that any of them are above taking a vindictive pot-shot?

It’s only inconsistent if they don’t like being mocked, themselves. If they’re comfortable with being mocked and are comfortable with mocking people, then they’re not being inconsistent. I think that the word “exceptionalism” has a place in that: I’d say that if I didn’t want someone making fun of me, but I was comfortable making fun of people, I was making an exception for myself (which is contrary to the “sauce for the goose” balance)

From my perspective, I’m comfortable with recognizing that policiticans are vindictive assholes; that’s what I expect.

polishsalami@#11:

I don’t think that Trolleyology (yes, they actually call it that) is all that bad. At least it gets people thinking about ethical dilemmas.

I’m not entirely sure about that. My inner experience when I think about trolley problems is that I imagine the situation, and then imagine what I’d do in it. So, all the “what would I do?” stuff really seems like post hoc justification: I’ve decided what I’d do and now I’m trying to explain why. That doesn’t help me with ethical dilemmas, though it helps me understand myself maybe a bit.

I’m also comfortable assuming that when we reason about what someone else would do in that situation, we’re imagining our own response and assume that other people would do what we would do because otherwise they’re not like us and there’s something wrong with them. It’s a sort of embedded Marcus Exceptionalism – it seems to me that I am always the ultimate arbiter of all moral dilemmas, I just project my views all over the place and sit in judgement when others don’t do what I would.

John Morales@#8:

I’ve always used the term ‘golden rule’ for the positive formulation, and the term ‘silver rule’ for the negative — the one you provided.

One formulation is prescriptive, the other proscriptive. Subtly different.

Good point, I like that.

(Then there’s the LaVeyan Satanic formulation: “Do unto others as they do unto you” ? )

I saw that on Tshirts back in the 70’s: they read “Do unto others, then split.”

The actual flaw is that, if you happen to enjoy being punched (fight club!), then you can morally-justifiably go around punching people and feel virtuous about it.

That’s also a problem with consequentialism: if you really enjoy being punched, you might have the belief that everyone else would be better off with a good punching, and then the best outcome for everyone would be to go around punching people. If someone complained you could shrug them off as clearly not understanding the situation, “this is for your own good.”

I’m more of a moral pragmatist.

Ethical principles, ethical heuristics, no worries. Consideration for others, sure.

Ethical (deontological) rules? Problematic.

I think we’re on the same page, mostly. I self-label as a moral nihilist because I cannot establish my principles and heuristics in a way that I can be sure I’m right, and I accept that I probably can’t communicate them adequately (because once peanut butter gets involved, things get complicated) So I think I have principles, I’m just deeply skeptical about our ability to share them or even understand eachother’s, so I “withhold judgement” and just do my own thing.

brucegee1962@#6:

One of my earlier memories is having the “Golden Rule” explained to me after I punched my older brother. (I don’t know why he didn’t just punch me back.) With the logic of children, I immediately concluded that this was great — any time I felt like punching someone, all I had to do was punch myself with the same degree of force first, and I was in the clear.

That’s pretty good.

Maybe the US should drop an equal tonnage of bombs on random US cities, before it bombs other cities! I bet we’d be a lot less warlike as a civilization.

Reginald Selkirk@#4:

As for ethical systems, none proposed are without criticism. I think the basic problem is that ethics were not systematically worked out from a central theory, but developed organically and empirically over the course of our evolution. Therefore it is perfectly natural that human ethics are inconsistent, and all attempts to pin them down with some underlying theory will probably fail.

That’s a good statement of one of the moral nihilism’s: you remain unconvinced by any moral system you’ve seen proposed, so you withhold judgement and do what you think is the right thing.

This posting was about my apparently arbitrary process of deciding what I think is the right thing in various situations, with an emphasis on that every situation is unique and it’s best to have generally applicable inner rules because they’re faster to evaluate in an emergency.

I guess I misread it then. Sorry.

I’ve seen the “absurd hypothetical” opinion on Pharyngula, so I must have had the idea on the brain.

Ideally, moral rules should be adaptable; you may never encounter the hypothetical scenario you thought through in advance but the principles work just as well in whatever scenario you do encounter.

In actuality, ascertaining the facts will always be a bigger barrier than applying the moral rules. The key distillation of the trolley problem isn’t the omission of moral complexity but of practical complexity; you know the trolley will kill 10 people if you don’t act and you know that acting will save them but kill one person and you know there is no other option (or in modified versions, you know of other options and their pitfalls). In the real world, such perfect knowledge of outcomes is unattainable.

Alas, a moral system must accommodate the facts in order to have any use.

I’m not sure what you mean by “complete constructive moral system.” From here, it seems you’ve constructed a moral system— a set of rules for guiding actions, for the purpose of reaching an implicit goal. It may be lightweight and it may not make some specious claim to being an Objective Fact, but it’s still a moral system.

That seems weirdly disproportionate. I’ve had someone put gum in my hair and I didn’t even think of resorting to physical violence in response.

Incidentally, I was told at the time that the best way to remove gum from your hair is to put peanut butter on it. So I actually put peanut butter in my hair IRL. It was the lesser evil. It was also a trolley problem, so go figure.

No.

Or if you are, then they’re better armed. Or they have ten friends who are all armed.

The point is, how do you deal with a scenario in which you are physically overpowered by people who just don’t subscribe to your moral system and have some pressing desire to put peanut butter in your hair? (Hey, that was your example.)

Note that “dealing with” a scenario can include preventing it from happening, not merely responding to it if it does happen.

Jessie Harban:

<snicker>

Then they’re not rules; they’re guidelines at best.

You endure it as best you can. “The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” Life’s a bitch sometimes, but that’s got nothing to do with ethics – it’s simply a matter of power.

The intersection of ethics and power is kind of a major issue.

Only if you’re on the side with more power.

Unless I’m completely misunderstanding you, your question is equivalent to asking “how do you deal with a scenario where somebody kills you?”

We’re coming to a time when the trolley problem is no longer hypothetical, due to the development of autonomous trolleys. This leads fairly quickly to (certain people) having to make the choice, in advance, of whether to risk killing the occupant of the trolley or some surrounding pedestrians, in certain unavoidable situations.

I shudder somewhat to realize that the people who will make these choices are the Silicon Valley programmers.

Jessie Harban@#21:

That seems weirdly disproportionate. I’ve had someone put gum in my hair and I didn’t even think of resorting to physical violence in response.

Yeah, I’ve got a crazy response curve. And the odd part is that I probably wouldn’t care about the peanut butter at all – if someone asked me “hey can I?” I’d probably say “sure” – but if someone did it, just to demonstrate dominance or to piss me off, I’d go non-linear really fast. For me it’s about the reasoning behind the thing, as much as the thing itself.

The best way to piss me off is to try to piss me off, because when I realize that someone is trying to piss me off, it works. I’m bad like that.

I was told at the time that the best way to remove gum from your hair is to put peanut butter on it. So I actually put peanut butter in my hair IRL. It was the lesser evil. It was also a trolley problem, so go figure.

I’ve had that happen to me, too. My hair’s so thick and crazy I just use scissors. It’s a simpler response because it also works for paint, polyurethane glue, epoxy, and some of the other weird stuff I’ve gotten in my hair over the years. I’ve gotten so much stuff in my hair over my lifetime that sometime around the 1980s I switched to “just keep it out of my eyes.”

The point is, how do you deal with a scenario in which you are physically overpowered by people who just don’t subscribe to your moral system and have some pressing desire to put peanut butter in your hair? (Hey, that was your example.)

Submit, get it over with, and then – depending on how I feel about the situation – forget about it or take revenge. Revenge is something I haven’t commented on before, in the context of moral nihilism, but I think it’s an extremely important part of human interactions, which is often swept under the carpet in an attempt to pretend that humans play nicely together.

Note that “dealing with” a scenario can include preventing it from happening

In your statement above, I take “physically overpowered” to mean that they’ve already caught me.

I’m with Sun Tzu and Bruce Lee: avoiding conflict entirely is a form of victory. I’ve found that there are relatively few situations in life where I’ve been cornered; I’m usually pretty good at seeing the bad things coming and being somewhere else. That’s a strategy.

But, to your point, there’s a problem with conflict, which is that you can have an aggressor who makes it clear that they will never stop, never back down, never negotiate, and will ante up every time you do. My comment on PZ’s posting about Scott Nickerson [pharyngula]

“There’s nothing wrong with him that extreme violence wouldn’t solve.”

(and my subsequent comment) If someone has decided to ruin my life, I’d kill them immediately if I could get away with it. Maybe even if I couldn’t get away with it. That would depend on their ability to make me miserable – a lifetime of someone stalking me or a couple years in prison? No brainer, especially if it means that they won’t have the pleasure of ruining my life. I imagine I’d try to ask them for clarification while I was trying to figure out the situation, “are you going to keep messing with me for years or is this just a short-term thing?” It seems to me that’s a pretty typical human conflict reaction – trying to see if an opponent is really interested in a deathmatch, or if they’re just doing threat-display. I’m fairly sure a lot of human interactions have ended where someone who was doing a threat-display got a faceful of unexpected deadly force because their threat-display was too good. Memo to threat-displayers: make sure it’s obvious but over the top.

Dunc@#25:

Unless I’m completely misunderstanding you, your question is equivalent to asking “how do you deal with a scenario where somebody kills you?”

I think that might be taking reductio ad absurdem a bit too far.

Another problem with these scenarios (as opposed to basic trolleyology) is that we’ve got an opponent whose intent we cannot determine with certainty. It’s like that wonderful scene in the opening of Reservoir Dogs where that guy jokingly asks Mr White “what if I kill you?” and White replies, “if you kill me in a dream, you’d better wake up and apologize.” How do we know whether a threat is real or just someone mistaking the situation? If our mental model of the opponent leads us to conclude it’s a serious threat then I think we’re probably able to justify (to ourselves) doing something to deter them, or even disable or kill them. But what if we’re wrong? It happens. Somewhere between “turn the other cheek” and “nuke it from orbit it’s the only way to be sure” is a balanced middle-ground, but that balance is entirely situational. It’s what trolleyology tries to abstract out, and I reject trolleyology’s argument that you can abstract enough that someone can answer “this is what I will always do.” I’m comfortable saying “probably” and waffling a lot. But trolleyology seems to treat our responses as deterministic. I’m skeptical.

Johnny Vector@#26:

I shudder somewhat to realize that the people who will make these choices are the Silicon Valley programmers.

Good point. I suspect we’ll do what we have always done: stumble around iteratively and establish an approximate baseline that seems reasonable to most people, then pat ourselves on our backs for being “moral” and having carefully considered the problem.

@25, Dunc:

No. It’s: “Consider a scenario in which someone you cannot physically overpower wants to make you suffer. How do you prevent that situation from occurring (or respond to it if it does occur)?”

The point I’m trying to make is that morality isn’t about individuals choosing what to do for themselves. “Here’s how I would respond” isn’t morality; it’s just your own desires. Morality requires at least some semblance of universality; “here’s what everyone is expected to do,” and in order to be meaningful there needs to be some enforcement mechanism or else the entire thing collapses into a might makes right scenario.

Which is “the side with more power?” I’d argue that the whole point of morality is to create a system in which there isn’t anyone with the power to oppress.

@27, Ranum:

Well, that’s the thing— how do you know why I put peanut butter in your hair? You can’t possibly know that I’ve done it for any specific reason, so you end up flying off the handle.

Though I’d argue that regardless of motivation, violence is never an appropriate response to peanut butter. Disproportionate response carries a substantial risk of escalation; if your response is disproportionate, it goes beyond reasonable self-defense and becomes assault which means I’m justified in using greater force in self-defense.

The person who put gum in my hair did it to piss me off, and even having learned that I consider violence to be a flagrantly inappropriate response.

Ah, the gum thing was back when I kept my hair short.

No. The scenario is hypothetical; prevention is just as good an answer as response.

Moreover, “prevention” doesn’t just mean taking effort to not get caught; it can also mean taking effort to prevent there from being anyone who can overpower you, or taking effort to guarantee that no one who can overpower you would be able to benefit from having done so over the long term, and thus wouldn’t bother trying.

The trouble is, you’re proposing amoral solutions— “(individual) might makes right.” Your reaction to the aggressor relies on your personally being able to overpower and kill them. If morality has any purpose, it’s to prevent scenarios in which you must individually overpower an aggressor or submit to their demands.

Realistically, you cannot use extreme violence (or any violence) against Scott Nickerson (or Trump, or any of a million powerful assholes) so proposing it as a solution is meaningless. Morally, you don’t seem to propose any real option, so their actions stand unopposed by default.

Then we’re going to have to disagree, because I don’t think that goal is even theoretically attainable. Morality and ethics aren’t about eliminating power, they’re about what you choose to do with it.

It’s not an all or nothing affair; morality will never obliterate the power to oppress and science will never be a perfectly objective truth-ascertaining enterprise, but we can incrementally inch our way towards that goal and call it societal improvement.

If you want perfect morality, you’ll need a perfect species.

It’s important to define the terms carefully here. Everyone has a certain capacity to act; some people have vastly disproportionate capacity. The capacity itself can be called “power,” but so can the vastly disproportionate capacity; everyone has at least some power in the first sense, but the term “power” is also used to refer to the second sense.

Or in other words, the first kind of power is what everybody has; the second kind is what the aristocrats have.

I’d argue the goal of morality is to eliminate the second kind of power; “power” in the sense of disproportionate capacity to act. How? By all of us selectively choosing how we use our power in the first sense; “power” in the sense of individual capacity to act.

So if you use “power” in the first sense of the term, you’ve not actually contradicted my idea.

That’s not morality, that’s politics. Politics is informed by morality, sure, but they’re not the same thing, any more than engineering is the same thing as physics.

Anyway, you’re the one who started out with an example about being “physically overpowered“. That’s not the sort of power that aristocrats have, that’s the sort of power which is an inevitable consequence of physical embodiment.

Jessie Harban@#30:

The point I’m trying to make is that morality isn’t about individuals choosing what to do for themselves. “Here’s how I would respond” isn’t morality; it’s just your own desires.

I tried to hoist the flag early and obviously, when I said I am a moral nihilist. That’s a form of skepticism that withholds judgement on the possibility that a shared moral system can be derived. I’m inclined to reject statements like yours by observing that “individuals choosing what to do for themselves” appears to be pretty much how things are and that therefore most people appear to also reject the idea that there’s a shared moral system. I’m not saying it’s impossible to have such a system, but rather that we clearly don’t. Speculating about moral systems that are not a matter of individuals doing whatever the heck they want seems to be a pretty pointless endeavour and I’m not engaging in it. I’ve been careful to delineate that my predictions of how I might behave in any given situation are guided by my own internal rules, which are ‘flexible’, fairly arbitrary and I don’t expect anyone to agree with them.

In everyone’s world, everyone else is the Melian.

I’m not a Nietzschean (at least not since high school. When all the other kids were reading Ayn I was reading Fred)

Morality requires at least some semblance of universality; “here’s what everyone is expected to do,” and in order to be meaningful there needs to be some enforcement mechanism or else the entire thing collapses into a might makes right scenario.

If you define “morality” as that an important part of it is that we agree on it, I don’t think I’ve ever seen such a thing. (some people would say “that’s ‘ethics’!” but in Marcus-land we’d be arguing about whether we’re talking about black unicorns or white unicorns)

If you define “morality” as a system of rules that people follow, then I think I’d accept an argument that there are 7+ billion moral systems on earth, and that the majority of them are unexplored and devoid of landmarks.

Googling “morality” returns:

I’m not trying to make a dictionary debater’s argument to destroy your vocabulary [stderr] I’m posting that because I’m so skeptical about “morality” that I’m not sure what even I am talking about, and I need it for reference.

Well, that’s the thing— how do you know why I put peanut butter in your hair? You can’t possibly know that I’ve done it for any specific reason, so you end up flying off the handle.

To you I’d be flying off the handle.

To me, I’d be being myself.

To Dunc I’d be, I dunno, let’s say “a bit twitchy about peanut butter.”

I observe that in situations in which a moral judgement is made, people’s behavior seems consistent with the idea that there’s no such thing as a shared morality. There may be shared cultural values but I don’t see those necessarily as “morals” because you can easily have a culture (hey: take a look around us!) in which individuals reject the culture’s values as “immoral.” So I don’t reify cultural values. Cultural values are what cops shoot you over.

Though I’d argue that regardless of motivation, violence is never an appropriate response to peanut butter. Disproportionate response carries a substantial risk of escalation; if your response is disproportionate, it goes beyond reasonable self-defense and becomes assault which means I’m justified in using greater force in self-defense.

Yeah, see? We can disagree. And as long as everyone keeps their peanut butter in their holsters, we can get along without having to explore who’s the Melian and what our cultural values are regarding peanut butter hair gel.

One of the things about moral nihilism is that it doesn’t mean I can’t choose to want to get along with other people.

The trouble is, you’re proposing amoral solutions— “(individual) might makes right.” Your reaction to the aggressor relies on your personally being able to overpower and kill them. If morality has any purpose, it’s to prevent scenarios in which you must individually overpower an aggressor or submit to their demands.

It’s “moral” to me! But I don’t expect everyone to share it, which is why I don’t try to promote my personal opinion as a moral system. (This post was more about describing how I make rules, rather than the rules themselves. And, as I pointed out in my trolleyology story, I don’t even bother trying to understand most of my rules. I just act.)

relies on your personally being able to overpower and kill them

A secret service guy? No overpowering; those guys are dangerous. He needs a drone strike.

Realistically, you cannot use extreme violence (or any violence) against Scott Nickerson (or Trump, or any of a million powerful assholes) so proposing it as a solution is meaningless. Morally, you don’t seem to propose any real option, so their actions stand unopposed by default.

Not at all! I can use extreme violence on anyone I choose to; I just may have downside costs that I want to avoid. The question is who’s the Melian. I’m not saying “might makes right” as much as that “right appears to be irrelevant” which is an observation consistent with historical reality.

I’m not proposing a moral basis for any action; that’s the point. So if someone is sufficiently pissed off at Trump (or threatened by Nickerson) and pops a bullet into either of them, I’ll shrug. I might decide it was an overreaction, or I might decide it was justified. Remember when the guy in Turkey shot the Russian ambassador? That was a political statement of a sort and I support his making that statement and experiencing the consequences of doing so.

I’m not a fan of the Golden Rule. Many people, who claim to observe it, mess it up. Ok, this one is turning into a rant about Christians. And they often follow this rule. At first…

“Would I like being hit?” “No, therefore I won’t hit others.”

“Would I like being murdered?” “No, therefore I will not kill.”

“Would I like it if my state forbade me from having an abortion?” “Yes, because I believe abortions are evil, therefore I will support a ban on abortions.”

“Would I like if somebody knocked to my door with an intention to start a discussion about Jesus?” “Of course I would love it, I always like talking about Jesus, therefore it is always ok for me to preach to others (even if they show signs of being unwilling to listen).”

For some reason people fail to ask the wider question – “Would I like if somebody who holds opinions different from mine started telling me how to live my life?” They never bother to actually do any of that de-contextualizing you talked about. I bet Christians would be really pissed off, if I started lecturing them about where they should stick their bibles. Yet they believe that they have a right to force me to behave according to their doctrines. A side note: I wish I was the first one to come up with this, but I’m not. There’s actually a website selling a Baby Jesus Butt Plug and a bunch of other cool and divinely inspired sex toys.

The Golden Rule is good at finding answers to simple questions, like, “Should I punch Bob in the face?” But it is bad at helping us find answers to more complex issues, like “Should the state legalize euthanasia?” Also, what if Bob really deserves to be punched, because he punched me first? And what if punching Bob would lead to a better outcome, because Bob is a serial murderer and punching him would put him off the streets. (Sorry, I’m not sticking to your peanut butter example.)

Personally, I’m mostly basing my actions on the Harm Principle (John Stuart Mill). This is mostly the result of the years I spent arguing with friends in my university’s debate club. I start with a premise that suffering of sentient beings is a bad thing, thus actions, which increase suffering, are bad. And vice versa. In the euthanasia example, I can evaluate, whether legalizing it would cause harm to a third party. Self-inflicted harm is irrelevant (if a Christian believes, that the person receiving euthanasia damns their soul to hell, this does not count, since each person is free to choose for themselves). I apply this not only for political decisions, but also for personal actions. Hitting Bob would cause him harm, so I don’t do that. If Bob is a masochist and asks me to hit him, there is no harm, so I am free to hit him. If Bob causes me harm by hitting me first, then I consider myself justified to defend myself by hitting him as well. If I know that Bob is a serial murderer, I can reasonably assume that not hitting him would cause harm to his future victims, while hitting him would be the right thing to do, since it takes him off the streets.

Of course this system of mine has a bunch of problems.

How small harm is acceptable? There are plenty of “small harms” that I have to accept. For example, driving a car pollutes air in the city, thus causing harm to those who have to breathe it. And, before you dismiss this example as unrealistic, it actually is a real problem in the city where I live. Cars in the city center cause air pollution levels to rise above what European Union bureaucrats deemed a safe level, and city authorities actually urge people to walk or ride a bike instead of a car for this reason (ok, traffic jams are another reason). Another example – mocking religious beliefs hurts believers’ feelings, so it could be argued, that there is some harm. I still do that anyway.

Another problem is human inability to always accurately predict the outcome of their actions.

Me sticking to the harm principle as basis has made my political opinions to be all over the place, thus making it impossible for me to relate to any party we have in my country (deciding who to vote for is tough for me). I support LGBTQ rights, euthanasia, abortions, prostitution, all imaginable sexual practices as long as everybody involved is adult and consenting, marijuana use, secularism etc. I also support free university/college education, free health care in state owned hospitals, guaranteed minimum income, tight regulations for businesses, especially banks. State owned houses, where the poor can rent apartments for cheap prices (free market is great with building homes for the rich, but there is too little profit in renting apartments to the poor, at least in my country). State owned and free kindergartens, free and healthy lunches at school for kids. State paid temporal leave from work for parents after the birth of a child. Lack of social welfare causes plenty of harm, so I must support it.

At a certain point, since these are all rules we’re holding in our heads, we’re going to have trouble holding them, and then we become unpredictable. In that case I would say we’ve become unpredictable because we have a broken ethical system (broken in the sense of: “I forgot big chunks of it”, which seems to be how some people behave…)

It’s not just some people. I’d say it’s the majority. People don’t think about ethical systems, they just do whatever their gut feeling tells them is the right thing to do. And it mostly leads to decent outcomes. There was some research by Paul Bloom, which indicated that even babies are endowed with compassion, empathy, and a sense of fairness. Researchers showed babies some puppet show, and concluded that babies preferred the doll, which treated other dolls kindly, as opposed to the mean doll. Of course, the gut feeling sometimes goes astray. For example, we treat members of our ingroup kindly and better than outgroups. And once people start dividing themselves into us and them, it gets easy to demonize “them” and lose any empathy towards those who are supposedly different.

That makes them harder for me to model in my imaginary future universe, so I am uncomfortable around them because they are unpredictable and therefore dangerous.

I doubt that. I find all those codes of conduct, which are devoid of rules, rather predictable. They are all based on cultural values and whatever the given society taught their people as right back when they were kids. If I know that somebody grew up in Germany, I can expect a set of rules, which are close to what most other Germans believe. If somebody grew up in Japan or some Muslim country, I can expect a different set of values. A conversation usually reveals what it is that a person considers right. Often, when it’s beneficial for them, people do what they want and rationalize afterwards. And, let’s be realistic, I also could do plenty of rationalization within what I described as my preferred method of making decisions. Let’s assume that action A leads to both positive and negative consequences. If I really want to do A, I can simply emphasize the benefits and downplay the bad consequences.

Ultimately everybody just does whatever the hell they want.