I’m going to do a couple of postings about causality, because it seems to me that how humans experience causality is of paramount importance to a lot of ideas such as “free will”, responsibility, and knowledge.

Presenting a philosophical framework in which to defend these ideas, however, is beyond me – so I’m going to approach the discussion casually, and I’ll be less rigorous about terminology than I’d have to be if I were going to try to defend my thoughts against a full-on skeptical enquiry.

I’m going to try to avoid making asssertions, since this discussion is sort of an oblique critique of Aristotelian ideas of causality. Let’s start by rejecting those as arbitrary.

Aristotle asserts that there are a variety of different kinds of causes: proximal causes, necessary causes, sufficient causes, final cause. Other than their potential usefulness as labels, we aren’t given a way to tell which kinds of causality are which, except for after the fact – which is how we humans appear to experience causality, anyway. In other words, after a tree falls in the forest, I can say “it was rotten at the roots, so it fell” or “there was strong wind so it fell” but it doesn’t make sense for me to say that before it falls (since it hasn’t fallen) and once it does fall, I can no longer really be sure which of the causes I assign to the event was really the cause. I start to have problems with cause and effect because the way we humans seem to assign them is 1:1 – there is A cause and AN effect, but reality appears to be much more complicated than that. Especially because reality doesn’t courteously come to a pause while we ponder cause and effect, it keeps right on rolling: what other things fell when the tree fell?

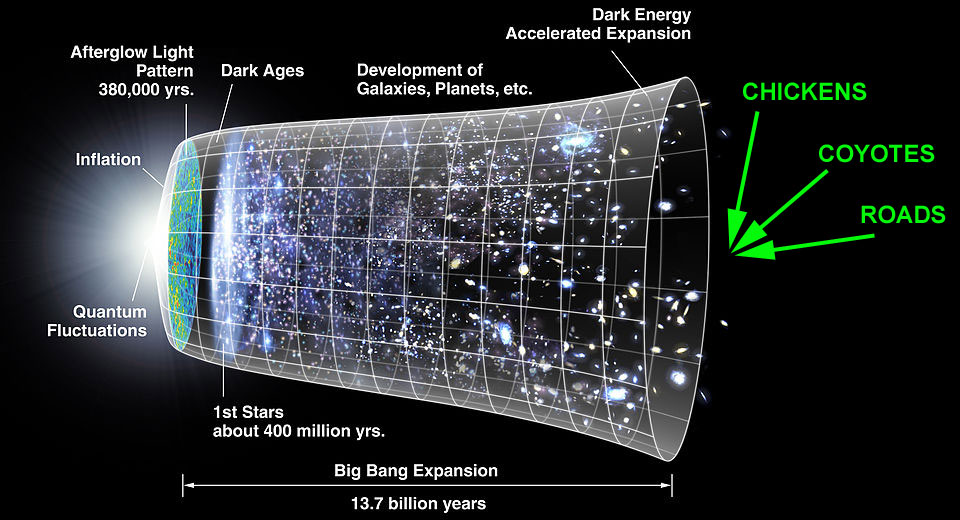

The tree fell because of the big bang

It appears to me that when something happens, it has multiple causes: the tree’s roots have to be weak or it wouldn’t blow over. But humans’ way of talking about cause and effect is to try to assign a 1:1 cause/effect relationship – which makes sense because otherwise we’re going to be unable to talk about cause and effect at all: were the roots 40% of the cause and the wind 60%? When Aristotle starts breaking causality into various types of causes, that’s pretty much what he’s saying. There are some causes without which an effect would never happen – the final cause – but there are other causes which lead up to the final cause, without which the final cause cannot happen. Aristotle’s example is teeth growing: they appear to grow because there are certain material causes (they must be physically assembled by the body via some process) but their final cause is teleological – we need teeth to chew with. Aristotle slides right by the problem that “having teeth” is a vague concept. At what point can we say someone has teeth? If we have trouble saying at what point someone has teeth at all, how can we say that something caused us to have teeth? If we’re going to say “the tree fell because the roots were rotten” we slide past the problem of saying what “rotten roots” means, and a pyrhhonian skeptic would probably appear to point out that our definition of “rotten roots” may be circular: we have rotten roots if they are so weak the tree falls down, therefore we can say that the tree fell down because it fell down. Ooops.

As I said in the beginning: I am not trying to present a philosophical world-view – I don’t have a framework in which to answer to these problems. In truth, I tend to be genuinely suspicious of people who do feel they have an answer, because I suspect they are engaged in motivated reasoning. Most of us will have encountered cause/effect based reasoning for the existence of god: there must be some un-caused cause, etc. I first started worrying about cause and effect because of that argument – the closer I looked at it the less I understood about cause and effect. Rather than believing in god, I just wound up confused.

“to avoid predators” (source)

“Why did the chicken cross the road?”

One of the many problems with that question is that it implies there’s a single cause for the actions of the chicken. But it seems to me that there are nearly an infinity of causes, if you want to start assigning causes:

- Because humans bred chickens

- Because there was a coyote chasing it

- Because of evolution

- Because chickens like to play in roads

- Because of the chicxulub event, which wiped out the dinosaurs and opened up new niches for life to evolve into, therefore: birds

- Because god said “let there be poultry, and roads”

- Because of The Big Bang

- It was trying to escape from Twitter

If we were to enumerate Aristotle’s causes, several of the ones on my list above are material causes, i.e.: “that out of which” the effect is made. After all, something made the chicken. But “evolution” or “humans breeding birds” or “eggs” or “grandma chicken” are equally good responses. We might say “let’s favor the ‘largest’ response on the list – i.e.: evolution had more to do with the creation of chickens than the chicxulub event, therefore it had more effect. But that’s a human conceit: the efficient cause – “the primary source of change” is simply whatever this particular human says it is; we have no means for determining primary source of change so our instinct appears to be to pick the earliest or most recent: the big bang, or the coyote.

“Fiat McNuggets”

Every effect has more than one cause. Simple cause and effect appears to be an illusion our brains create so we can cope with reality.

This is where I get off the trail and wander out into the weeds of nihilism. It appears to me that “cause and effect” is nothing more than a word we use – a shorthand, if you will – for our personal understanding of something that we observe. And our understanding is always limited by our senses and perspective, of course. Let’s reconsider the chicken, and let’s suppose for the sake of argument that there is a coyote stalking it. I observe the coyote and assign the coyote’s threatening behavior as one of the causes of the chicken’s crossing the road. But if the person standing next to me is positioned such that they don’t see the coyote (due to a philosophically convenient intervening rock) they may interpret the chicken’s road-crossing as due to an evolved-in fondness for roads, if they are an evolutionary psychologist. Then we’re right back to extreme skepticism: because of our inability to know anything due to the fallability of sense input (#include <skepticism/pyrrhonism.h>) we can’t make claims to knowledge about why the chicken did anything, but worse still: the tool we would use to talk about it between eachother is mere language, which is not reliable enough. We are left wondering if there’s a thing we would agree is a “chicken” at all, let alone a road-crossing event such as we would collectively agree that there had been a road, and it had been crossed by a chicken, and there was a thing we call a “coyote” involved, ad infinitum.

If I did have a framework for talking about causality, it would probably sound almost like woo-woo: “cause and effect” are the words we use to talk about our limited understanding of the events we are discussing, as a way of packaging up those events that we perceive as directly affecting them. Meanwhile, it seems to me now that cause and effect are not a simple linear chain of one event leading to another – the causes are the totality of prior events and the effects are all subsequent events. Causality is not a line, it is a meshwork that branches infinitely, because the closer we wish to examine any event, the more causes and prior causes we can identify. “Make me one with everything,” the buddhist said to the hot dog vendor. The hot dog vendor replied, “The big bang already did. That’ll be $5.”

So now I am back to my starting-point: “we experience causality.” It is difficult to convince me that we know anything about causality, aside from its being a handy organizing principle we can apply verbally when we are trying to communicate about something. That could go some way toward explaining why, when humans talk about cause and effect, we are all over the place – some of us think the chicken’s actions were purely internally-driven (“free will”) while others think the chicken was acting in a context where its options were constrained by the coyote (“it’s a meat robot programmed to avoid coyotes”) and – in the same breath, we can ascribe the entire thing to god or the big bang or both or neither.

From a practical standpoint, in order to make science work, we need to think about cause and effect as if it’s a simple linear model. In order to eat, our distant ancestors had to model game animals’ motivations in a simple linear model of cause and effect: if I wait for the chickens’ ancestors to cross the road and come to the watering-hole, I can eat one of them. It’s tempting, at this point, to adopt an evolutionary psychology-style “just so story” – our brains’ ability to interpret cause and effect is optimized to assign proximal cause to the point where we are most likely to be able to take an action that will confer a survival advantage.

Stanford Library of Philosophy: Aristotle on causality

Stanford Library of Philosophy: Vagueness

This is an hour-long talk, but the first 20 minutes or so covers the historical perspective of causes vs the perspective of modern physics.

Sean Carroll: “The Big Picture”

Causes and effects are fundamentally contingent on the laws of physics.

So addressing the tree, for example: The tree fell down because the force of the wind blowing on the trunk and branches and leaves resulted in enough torque to overcome the strain strength of the roots, which had been greatly weakened by the growth of bacterial colonies that chemically altered part of those roots by metabolizing them into more of themselves (and so on — I don’t actually know the biophysics of “rot”, but I should think that actual tree botanists/arborists do), whereupon the overbalanced mass of the tree, in conjunction with the force of gravity, began to move towards the center of the Earth (and stopped when it hit the surface)

(and maybe that should have read “fungal” rather than “bacterial” colonies — or maybe rather: “some combination of fungi, bacteria, and mold, in metabolically interacting” colonies)

Just to up the pretension here…

I think one of the important philosophical issues that needs to be addressed when thinking about causality in this way is formally known as mereology, which is in essence the study of what things are. That is, what “things” are.

There’s a collection of objects on my hotel room side table right now, including an iPad, sunglasses, a brochure, and some empty little rip-off bottles of booze the hotel provides (it was a long night). All of those we instantly classify as “things”, and, equally importantly, we do not classify the totality of them as a single composite “thing”. There is no stuffcurrentlyonmyhotelsidetable thing. That would be silly.

But it’s not like there’s a set of html tags attached to each of these things defining it as a genuine thing with particular properties. There are… molecules, and atoms, and protons and yadda yadda, and a whole lot of them happen to be temporarily arranged such that they travel together and maintain roughly the same spatial relationship to each other. Which is nice, because it means when I pull one corner of my iPad, the other corners come with it and don’t just stay on the table. “I pick it up”, a sentence which conceals a vast and complex set of physical processes, in which the attractive forces between its constituent molecules sum to much higher than gravity and friction and so on, so they all move together, rather than falling apart.

Systems of particles that have enough temporary unity to be acted upon in particular ways are easy “thing” candidates. What someone (Austin, I think?) called “medium-sized dry goods”, which are the prototypical things. Things are useful conceptual shorthands that allow us to think and talk about existence. A great deal of our thought is OOP, I guess, except “classes” are not defining the things-in-themselves (hi Kant!), rather they are our attempts to model them. (And, it is important to note, generally speaking these models are pretty good, especially where medium-sized dry goods are concerned.)

Ok, that was long winded. The point (I have one?) is that if you’re going to talk about A causing B, that presupposes an A and a B. This is clearly problematic when you’re talking about “evolution” or what have you as a cause, because I don’t think anyone thinks of evolution as a “thing”. But it is impossible (or at least really hard) not to reify our As and Bs. So our causal language becomes silly very quickly, and clearly inadequate for the task of providing models of anything beyond very constrained sets of processes operating on medium-sized dry goods.

If I read your post correctly, I think you’re thinking about better ways to deal with the problem outlined in that last sentence. Uh… good luck? Let us know when you’ve figured it out, it will be very useful.

Part of the problem is that we see cause in relation to what we consider the normal background. We can take two identical trees, that both fell over because their rotten roots couldn’t hold it against the force of the wind.

In an environment where rotten roots are usual but strong winds are not, we will assign cause to the strong wind. In an environment where strong winds are common but rotten roots are not we will assign cause to the rotten roots.

There’s a relevant Robert Anton Wilson quote from the Schrödinger’s Cat trilogy that I’ve seen circulating on FB recently:

Dunc:

<snicker>

Quaint fabulism, but counterfactual.

—

In passing, Marcus’ own citation belies his purported enumeration of Aristotle’s four causal categories, which actually are the material, formal, efficient, and final, not the proximal, necessary, sufficient, and final.

(Aristotle’s categories at least have the philosophical merit that they are independent of each other)

PS aka what, how, whereby and why. The “final” cause concept is mired in teleology.

Mistakes are made so that they can be corrected ⇐ teleology!

Owlmirror, !

I think you’ve just explained theodicy.

Owlmirror@#1:

I watched that, and I need to watch it again, it’s good stuff.

It appears to me (though I am doubtless bringing my own preconceptions into my interpretation) that Carroll makes a good case for cause and effect being a product of physical law – which I agree with – particularly with respect to the order of events. I’d previously encountered (I think via Feynman) the idea that entropy is what keeps reality from being completely reversible, or how we can discern the direction in which time’s arrow is pointing – Carroll really explains that nicely. And that’s an important part of causality that I hadn’t really gone into because I didn’t think to mention it because “everyone knows that” (except we don’t, do we?)

Carroll is right to the extent that cause and effect is entirely a process of physics, but that doesn’t really address the problem I’m trying to raise, which is that our experience of cause and effect is variable in scope and allows us to make multiple accurate statements about cause/effect. As you point out, “the tree fell because …” can be accurately ascribed to physical causes (wind, bacterial action) but it can also be accurately ascribed to physical causes of those causes, as well: the heat of the sun powering the wind, ancestors of bacteria producing more bacteria, etc. We can order those causes in time – and that’s not arbitrary – so Carroll has helped us somewhat, but we can zoom in infinitely on the time-line until we’re back to vague concepts: was there a particular bit of lignin that a given bacterium ate that “destroyed” the root? Was there a certain number of air molecules moving at a certain speed that pushed the tree over, rather than merely straining it? It seems to me that the physical explanation gives us a way of ordering events (which is good) but doesn’t really let us dispell the vagueness surrounding the whole event.

My observation regarding the vagueness is that it appears to have something to do with the scale at which humans think (we don’t see an individual bacterium eating the critical piece of root and our skin and hair are not good enough wind-speed measurers) – as well as how we use language. I’m fairly comfortable with saying that part of what’s going on is that our use of the word “falling” embeds and embraces the vagueness of the event – by definition, when we say a tree is “falling” it is no longer upright and its roots have failed, etc. But then we seem stuck – we observe it is “falling” (or “fallen”) but then we hand-wave off the causes/effects involved in the fall as being below our radar-screen. What if the tree was not “falling” until a particular ant climbed to a certain height and altered the balance of the tree just enough? We sweep the ant’s role under the carpet because clearly bacteria and wind were involved and we can know something about them, but we didn’t see the ant. Perhaps that’s not a great example, but I’ll ask your generosity in trying to understand my point: did our use of the word “falling” represent our decision as to how we are going to scope cause and effect in the case of the tree? One final meandering thought about that: we may observe someone looking at a rotting tree and saying “that tree is falling down” as a way of encapsulating a prediction that it will someday complete the process of falling down that it may have begun some time ago. As a physicist, Carroll is – probably – going to gravitate toward a physical explanation of a phenomenon. I wonder what a linguist would say. (clearly, I am not one)

(and maybe that should have read “fungal” rather than “bacterial” colonies — or maybe rather: “some combination of fungi, bacteria, and mold, in metabolically interacting” colonies)

Was the cause 83.2% the fungi (which are the primary decomposers of wood) and 16.01% the bacteria? I left a few points for the woodpecker.

EnkidumCan’tLogin@#

I think one of the important philosophical issues that needs to be addressed when thinking about causality in this way is formally known as mereology, which is in essence the study of what things are. That is, what “things” are.

Oh, cool! Thank you for introducting me to a new -ology! I’ll bust a few scrolls of google.

here’s a collection of objects on my hotel room side table right now, including an iPad, sunglasses, a brochure, and some empty little rip-off bottles of booze the hotel provides (it was a long night). All of those we instantly classify as “things”, and, equally importantly, we do not classify the totality of them as a single composite “thing”. There is no stuffcurrentlyonmyhotelsidetable thing. That would be silly.

I’m not entirely sure I agree with your example; I might casually refer to that mass of stuff over on the side table as “my stuff”, embracing it abstractly; my inner thought would probably be something like “that which I have to sort through when I pack my bags before I check out and head to Atlanta” You picked a very timely example.

Still reading the piece on Stanford Philosophy Library about “mereology” (http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/mereology/) it appears that this is exactly the problem that’s bothering me: when I point to a table and say “that is a table” I have not really addressed whether I’ll still consider it to be a table if one of the legs is removed. Or two. My guess is that if I walked into the room and the table had sufficient legs to stay upright* I’d call it a “table” even if you removed one of the legs and it no longer stood upright. But if I entered the room and it was in the one-fewer-leg configuration, I might call it “a table-top” because I hadn’t seen it as a “table” I believe one of the ancient Greek philosophers** used a similar example in a sort of skeptical nihilism: we can talk about such-and-such being a “chair” but there’s a question of whether we can define “chair” adequately. That brings me back to vague concepts in language.

f you’re going to talk about A causing B, that presupposes an A and a B.

I like that.

This is clearly problematic when you’re talking about “evolution” or what have you as a cause, because I don’t think anyone thinks of evolution as a “thing”. But it is impossible (or at least really hard) not to reify our As and Bs. So our causal language becomes silly very quickly, and clearly inadequate for the task of providing models of anything beyond very constrained sets of processes operating on medium-sized dry goods.

That also sounds right to me. I do think of evolution as a “thing” but that’s probably because I reify it. Or, to be honest, maybe I reified it in the process of coming up with my example – I can’t really tell anymore. At least I didn’t say “the invisible hand of the market pushed the tree over” – but people do say things like that and I think they actually are ascribing cause (and thus effect) to vague concepts.

If I read your post correctly, I think you’re thinking about better ways to deal with the problem outlined in that last sentence. Uh… good luck? Let us know when you’ve figured it out, it will be very useful.

Not a chance, sorry. Right now I feel that almost Chomsky-like: our use of language is part of how we scope cause and effect, not the other way around, and that language is almost always vague and the only reason humans think they understand eachother is because the mouth-noises we make just happen to trigger certain brain-signals in other people, some of the time, kind of.

(* This gets nasty, and I had to rewrite that several times as I realized that I even own a one-legged bar-table. I can’t say my own table is not a table if it has fewer than 3 legs!)

(** I’m tempted to attempt a joke on Plato’s name, but I’m sure I’ll stumble on the Greek)

Marcus @10:

That’s not about vagueness, it’s about ignorance. We don’t know. A lot of the time, we don’t want or care to know about such details. That’s the essence of entropy, actually. What useful things can we say about a container with gas in it? Should we try to plot the trajectories of the molecules as they bang around against each other, and the walls of the container? Neither doable or particularly useful, I think we’d agree. So we ignore the individual positions and trajectories, and focus on properties that are useful at our scale; pressure, temperature, various notions of energy, and entropy. These properties emerge from the underlying physics.

And entropy is a measure of our ignorance of the system under consideration, since it’s proportional to the logarithm of the number of microstates (roughly, the number of ways the molecules could be arranged) accessible to the system.

As I allude to above, the process isn’t vague, just bloody complicated. Vagueness only arises when we ask questions we can’t answer.

Rob, Marcus actually linked to the entry on vagueness!

And yeah, it is about vagueness — a form of the sorites problem, in the case you quoted.

John, and I’m going all epistemicistic on that shit! Because it’s the only reasonable thing to do other than nuking the never-ending nonsense from orbit.

Rob, do you consider vagueness to be a (um) vague concept, or do you actually think it’s a nonsensical concept? Or perhaps inapplicable in this context?

I personally think Enkidum made a good point.

—

Marcus, I think the Stanford site is pretty good, but sometimes it’s a bit abstruse; The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy is also very good, and often more accessible.

(Wikipedia is iffy at times)

Depends – did somebody recently clear-fell a nearby upwind area of forest for development, exposing the tree to stronger winds than it has experienced during its growth?

John @15: I thought I made it pretty clear that what Marcus called “vagueness” I associate with “ignorance” or “unknowableness”. Sure, it’s useful, in that it tells you you’re probably barking up (or along, if it has fallen) the wrong tree.

Rob, obviously, you didn’t make it sufficiently clear to me, and so I appreciate your clarification: you consider it inapplicable in this context.

Rob Grigjanis@#12:

That’s not about vagueness, it’s about ignorance. We don’t know. A lot of the time, we don’t want or care to know about such details

I see from your later comments that you don’t appear to be a fan of challenges to scientific epistemology, specifically induction. I introduced vagueness as a part of the problem because I was also trying to avoid it – but, let’s go: science is a technique for exploring our understanding of cause and effect, by forming a theoretical framework of cause and effect, then devising experiments that can disconfirm that relationship. If the experiments continue to fail, or the framework has predictive power, we eventually allow the framework to become part of our body of knowledge. One of the reasons why scientists are so careful to try to identify controls in their experiments is to remove that ignorance about cause and effect that you refer to. That’s why experimentalists are at such pains to remove all other possible causes that may influence an experiment (Richard Feynman’s story about rat-running in “Cargo Cult Science” is a perfect example: http://calteches.library.caltech.edu/51/2/CargoCult.htm ) So I’m not comfortable saying “it’s ignorance” – perhaps in the example of a tree falling down, we don’t really need to be able to say we “know” the cause of the tree’s fall, but outside of trivial examples we need to be careful not to accept ignorance, or we’ve thrown science under the bus.

Vague concepts are also an interesting problem for scientific epistemology, as well, which is why I think that “real scientists” have let psychology and the social ‘sciences’ thrash around helplessly with behavioral inventories: they are trying to de-vagueify vague concepts and it hasn’t been a particularly successful program, so far.

That’s the essence of entropy, actually. What useful things can we say about a container with gas in it? Should we try to plot the trajectories of the molecules as they bang around against each other, and the walls of the container? Neither doable or particularly useful, I think we’d agree. So we ignore the individual positions and trajectories, and focus on properties that are useful at our scale; pressure, temperature, various notions of energy, and entropy. These properties emerge from the underlying physics.

I agree about the entropy. It doesn’t seem to me that humans operate at a scale where that is an answer that would be accepted at the macroscopic social scale: “I parked my car on top of that guy because, hey, entropy” In our social interactions we appear to be constantly assigning causes to effects, and we ignore that effects have many causes, and causal chains go back farther than we can understand.

If I understand what you’re saying (and I think I do) there’s a certain scale at which it’s reasonable to not try to fully enumerate causes and, yes, in small closed systems that’s going to make sense. Too bad we don’t live in one of those.

And entropy is a measure of our ignorance of the system under consideration, since it’s proportional to the logarithm of the number of microstates (roughly, the number of ways the molecules could be arranged) accessible to the system.

I agree with that, and that’s a really cool way of explaining how we can measure ignorance about a system. I’m going to have to noodle about that one for a long time. I really like it.

For human-scale systems, then, our ignorance is going to be infinite (sort of the same argument for the same reasons as why I hypothesized that the causes of any given event are more or less infinite when we start looking at them closely) That does pretty thoroughly gut epistemology, though, given that we’re hugely ignorant of even a smallish system, how can we draw inductive conclusions about cause and effect in anything larger?

Vagueness only arises when we ask questions we can’t answer.

Isn’t that most of them?

Dunc@#16:

Depends – did somebody recently clear-fell a nearby upwind area of forest for development, exposing the tree to stronger winds than it has experienced during its growth?

Trees only fall due to the invisible hand of the market if there’s a libertarian nearby to hear them.

Rob Grigjanis@#17:

I thought I made it pretty clear that what Marcus called “vagueness” I associate with “ignorance” or “unknowableness”. Sure, it’s useful, in that it tells you you’re probably barking up (or along, if it has fallen) the wrong tree.

I think I understand you, and I’m OK with what you’re saying, but it does seem to me then that most of what we’d call cause and effect is unknowable. That’s problematic because there are huge social constructs (e.g: “justice”) that are implicitly based on cause and effect where the myriad of subtleties make them vague. If I’m arrested for throwing Sam Harris in front of a trolley, they’re going to try to hold me responsible and I won’t get very far with a defense claiming that death is a vague concept and besides, I didn’t hurt him the trolley did, etc. It is actually true that I didn’t hurt him, the trolley did – but humans somehow auto-scope causality to the convenient “right” point even though it appears very hard to me to tell why that specific point. I’m vaguely reminded of the scene in “Repo Man” where Otto’s skeevy friend gets killed in the convenience store robbery and says “I blame society…” How do we decide the scope?

John Morales@#6:

In passing, Marcus’ own citation belies his purported enumeration of Aristotle’s four causal categories, which actually are the material, formal, efficient, and final, not the proximal, necessary, sufficient, and final.

You are correct. I was confused by memories from high school, and didn’t cross-check myself. Thank you.

Marcus @19:

We’re talking about different kinds of ignorance. If you’re studying the relationship between pressure and volume at constant temperature in a litre of gas, you’re probably ignoring the motions of individual molecules, and not thinking about removing that ignorance.

Of course, it’s not always clear from the outset what is or isn’t ignorable. In most biology experiments, you wouldn’t even think about quantum mechanics (would you, biologists?). But quantum coherence does seem to be important in some biological processes (photosynthesis, bird navigation).

It makes sense in any sufficiently complicated system, open or closed. At different scales, patterns emerge that require models which can look radically different from underlying models, if we want to make sense of them. And that involves ignoring (i.e. not fully enumerating) many of the details that are important at lower levels. This applies equally to thermodynamics and sociology.

Sure! A big part of

sciencelife is figuring out what the right questions are. The ratio of useless to useful questions is always huge.