Edited from “Rules for Radicals” by Saul Alinsky

The First Rule: Power is not only what you have, but what the enemy thinks you have.

The Second Rule: Never go outside the experience of your people.

The Third Rule: Wherever possible go outside of the experience of the enemy.

The Fourth Rule: Make the enemy live up to their own book of rules.

The Fifth Rule: Ridicule is man’s most potent weapon.

The Sixth Rule: A good tactic is one your people enjoy.

The Seventh Rule: A tactic that drags on too long becomes a drag.

The Eighth Rule: Keep the pressure on.

The Ninth Rule: The threat is usually more terrifying than the thing itself.

The Tenth Rule: The major premise for tactics is the development of operations that will maintain a consistent pressure on the opposition.

The Eleventh Rule: If you push a negative hard and deep enough it will break through into its counterside.

The Twelfth Rule: The price of a successful attack is a constructive alternative.

The Thirteenth Rule: Pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it.

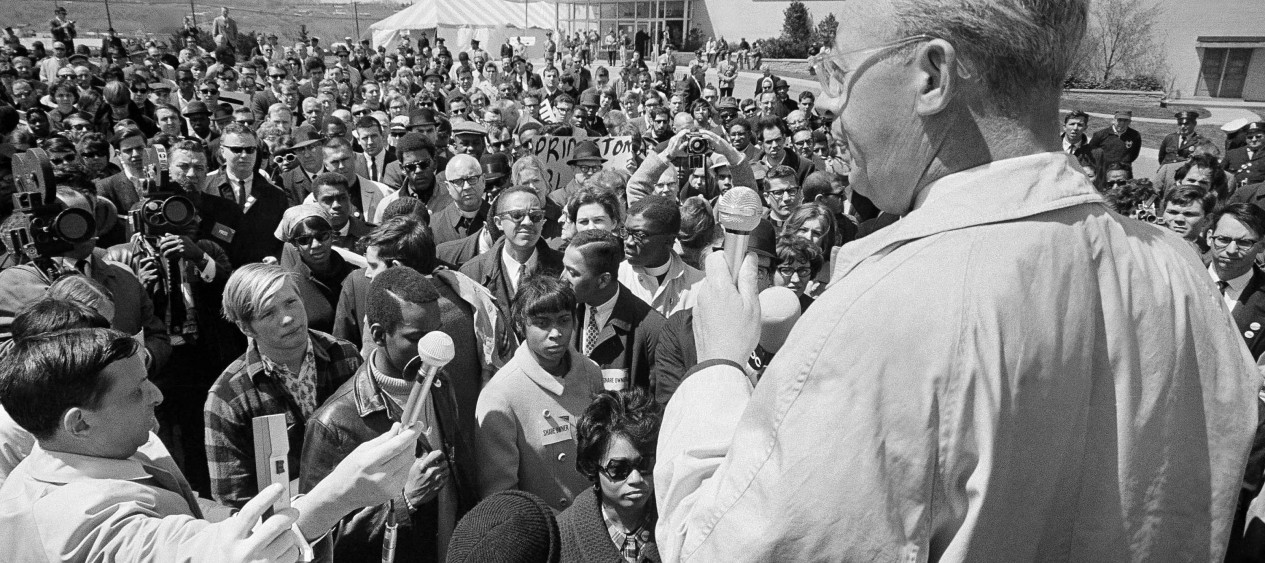

Alinsky, microphone in hand

Alinsky’s view of tactics is forthright and – I’m probably reading into it – profoundly skeptical.* He seems to recognize that all politics is manipulation and that we’re endlessly dealing with the products of manipulation, so manipulation is our only tool. You’ll notice that there’s no appeal to “right” or “wrong”, Alinsky’s approach is concerned with what works. I often wonder if that’s why he’s seen as such a scary person by authoritarians: they want to convince themselves that they’re right and – in accordance with his Third Rule he’s going outside of the experience of the enemy and ignoring that they want to think they’re right. Alinsky’s tactics exploit the intellectual laziness of the authoritarian mindset, which generally wants to assume that they’re correct (if not right) and not examine their presuppositions more carefully; when you’re up against an opponent that follows their presuppositions, you can fairly accurately predict how they will respond.

The Seventh Rule, and the Third Rule, combined, encourage the user to explore all the options on the battlefield, which is the main characteristic of great tacticians: use everything and don’t simply assume the engagement is going to proceed in the same old way, to the same old conclusion. Before Napoleon Bonaparte became hidebound, his great victories were examples of making the enemy fight outside of their comfort-zone.

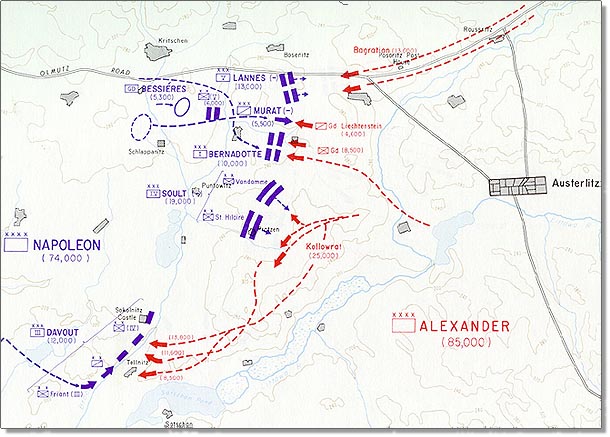

maneuvers at Austerlitz

In a signature victory, Napoleon realized that the Russian army, which outnumbered him slightly, typically didn’t have very good command/control, and he decided to take them out of their comfort-zone by encouraging them to try a more complicated maneuver than he thought they were capable of. At the opening of the battle, Marshall Davout was ordered to move up on the Russian left flank (lower left of the illustration) so that the Russians attempted to re-orient and block him, which disorganized them and opened them up to a hammer-blow attack straight up the center from Marshall Soult’s force. The genius of Napoleon’s play was at multiple levels, first, if the Russians had maneuvered neatly and not gotten disorganized, they still would have split their forces and potentially left themselves open to being defeated in detail. Secondly, if the Russians had responded effectively by falling back onto their flank, so what? At least they weren’t attacking.

Napoleon’s play worked exactly as he expected it to: the Russians were out of their comfort-zone, and didn’t know how to maneuver like the French, and were decisively crushed. The Russians maneuvered in the same old way, and Napoleon crushed them in the same old way. Wellington said that of Napoleon’s army after Waterloo, “They come on in the same old way, and we sent them back in the same old way.” Napoleon had stopped innovating.

Alinsky’s views on tactics are simply stated, yet deeply refined.

I remember specifically that when the Woodlawn Organization started the campaign against public school segregation, both the superintendent of schools and the chairman of the Board Of Education vehemently denied any racist segregationist practices in the Chicago Public School System. They took the position that they did not even have any racial-identification data in their files, so they did not know which of their students were black and which were white. As for the fact that we had all-white schools and all-black schools, well, that’s just the way it was.

If we had been confronted with a politically sophisticated school superintendent he could have very well replied, “Look, when I came to Chicago the city school system was following, as it is now, a neighborhood school policy. Chicago’s neighborhoods are segregated. There are white neighborhoods and black neighborhoods and therefore you have white schools and black schools. Why attack me? Why not attack the segregated neighborhoods and change them?” He would have had a valid point, of sorts; I still shiver when I think of this possibility. But the segregated neighborhoods would have passed the buck to someone else and so it would have gone into a dog-chasing-his-tail pattern – and it would have been fifteen-year job to try to break down the segregated residential pattern of Chicago. We did not have the power to start that kind of conflict.

It’s rare to encounter such clarity about tactics and strategy.

A note on style: Alinsky’s text includes the rules in blocks of text with his explanation of the rules. I extracted them gingerly and put them all together, trying to retain the flavor with Alinsky’s long-text numbering scheme. Because I substantially changed the format of the text, I did not block-quote it.

The entire discussion, in Alinsky’s original form, is highly worth reading.

I’m fascinated by the degree to which Saul Alinsky has become a scary nightmarish figure for the authoritarian end of the political spectrum. Is it because Hillary Clinton wrote her polisci thesis on Alinsky, and met with him, and caught his cooties? It’s not as if Clinton came away from the encounter radicalized – if anything, it seems that Clinton rejected Alinsky’s view of community politics in favor of more centralized politics. I believe that when the Clintons first came to power and Hillary tried to tackle medical insurance, that she was actually trying to improve things. They underestimated the forces that were arrayed against them.

Saul Alinsky: Rules for Radicals (amazon) (archive.org)

(* I used the word “nihilistic” but nihilism has been demonized to mean “destructive” instead of “rejecting apparent morals”)

I doubt that many of them are any more familiar with his actual ideas than they are with the details of Marx’s critique of capitalism. They’ve just been trained that “Alinsky = bad”. It might as well be “fnord”.

(Over at the inimitable Alicublog, it’s a running joke – any time a wingnut says “Alinsky”, take a drink.)

Too true – Alinsky and Marx, although Trump seems to prefer talking about Sidney Blumenthal… I’m not sure why, as I expect most people haven’t heard of him.

I have picked up Alinksy’s “Rules for Radicals”, which I hope to get around to reading in the next couple of years (I have quite a backlog). Is this one of your Recommended books?

In your summary of the list, I immediately noticed the application to military tactics. (1) and (9) look like they would supplement each other nicely, and (8) and (10) seem redundant – but perhaps there is more detail in the book that would separate the two…

Dunc@#1:

I doubt that many of them are any more familiar with his actual ideas than they are with the details of Marx’s critique of capitalism. They’ve just been trained that “Alinsky = bad”. It might as well be “fnord”.

Yes, It certainly seems to be that that’s what’s going on. Fnord fnord fnord!!

It’s just received wisdom, { the devil, communism, socialism, saul alinsky } is bad because the guy in the big hat says so.

felicis@#2:

I have picked up Alinksy’s “Rules for Radicals”, which I hope to get around to reading in the next couple of years (I have quite a backlog). Is this one of your Recommended books?

It was the second book I put on the list. So, enjoy your guaranteed reading experience(tm) – offer void if either of us die before you get to the bottom of your queue. I’m the same way.

In your summary of the list, I immediately noticed the application to military tactics. (1) and (9) look like they would supplement each other nicely, and (8) and (10) seem redundant – but perhaps there is more detail in the book that would separate the two…

The text has a lot more explanation; I extracted the summaries. That’s why I highly recommend the text.

Alinsky’s ideas definitely apply to military tactics, which is why I went into the apparent digression about Austerlitz. I actually put some effort into mapping some of Alinsky to Sun Tzu but they approach problems at a different level of abstraction.

I’ll have to pull out Sun Tzu and reread him (and, perhaps Musashi) immediately before Alinsky.

Fortunately, I read fairly quickly – I expect I’ll get to Alinsky in around ’18. I purchased the book independent of your guarantee, so – on the off chance I end up not liking it, I won’t take advantage – I was just curious.

felicis@#5:

I don’t think Musashi will map very well onto community organizing, unless you stretch it very very hard. Going from memory, I think he writes a lot about the timing of fencing beat attacks. That miiiiiight map to The Seventh Rule but only after a few beers.