Last Friday, I participated on the panel that discussed Science and Religion. The room was full (I estimate well over 100 people) showing how much interest there was in this topic amongst students, staff and faculty. It lasted about 75 minutes but many people stayed on afterwards to discuss in small groups. I spent about 90 minutes afterwards talking with some people and it was a lot of fun. What follows is a summary of the discussion and Q/A that focuses mostly on the topics that interested me.

The moderator was Bill Deal (a professor of Buddhist studies) who began by pointing out correctly that when people talk about religion in the US, they are often referring only to the monotheistic Abrahamic triad of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and ignoring other religious traditions. He also pointed out that even treating those three religions as single entities was a mistake since those labels encompassed a wide variety of belief structures within them. Before he introduced the panel he mentioned two popular arguments by which science and religion are said to be reconciled.

One was NOMA, the acronym by which Stephen Jay Gould’s rather pompously named Non-Overlapping Magisteria argument is referred to these days, which says that science deals with the material world while religion deals with the world of morals and values and that these two worlds do not overlap and thus there need be no conflict. The other argument is that there are many theologians who are supporters of science and many eminent scientists who are religious. He singled out Francis Collins, head of the NIH and leader of the Human Genome Project, as an example.

The first speaker Patricia Princehouse is a professor of biology who was a student of Gould and she seemed to feel that there should be no conflict between science and religion and she faulted those Christians who taught children religious dogma concerning the origins of species and the age of the Earth so that when students came to college and found that what they thought they knew about science was all wrong, felt forced to choose between science and religion. She felt that this was a tragic situation that could have been avoided if the children had been taught ‘proper’ science and religion. She seemed to think that the conflict between science and religion was caused by people having wrong ideas about either one or both.

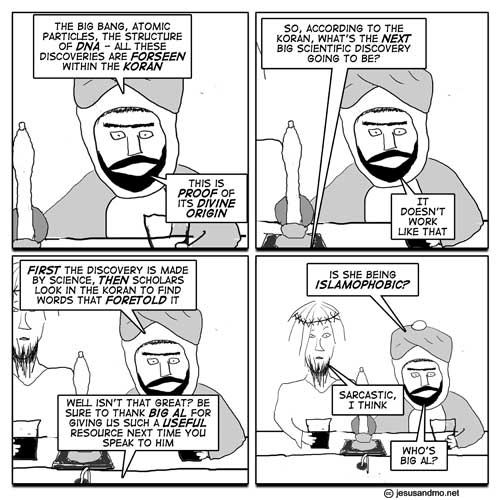

The second speaker Sree Sreenath is a professor of electrical engineering who said that he started out religious, became an atheist, and then later returned to Hinduism. He spoke about the variety of philosophies in Hinduism, some of which had a god, and others that did not and he said that you could pick which ones you were comfortable with. He gave an anecdote about a physician who had witnessed in the Himalayas someone being healed of some problem by a form of mystic treatment. He also spoke about how some Hindu texts anticipated the heliocentric model long before Copernicus. He seemed to be impressed by these things, though I could not see why. After all, Aristarchus also suggested the heliocentric model 2,000 years before Copernicus. In addition, it is always possible to comb through religious texts and find some passage that seems to ‘predict’ some later scientific development. Christians routinely do this with the Bible and Muslims do this with the Koran, thinking it gives credibility to the divine origins of their books. Jesus and Mo gave the definitive smack down to that way of thinking.

When questioned by me later as to whether he believed that god intervened in the world at all, he said no, so he may be a deist of some kind, but that would not square with his claims of cures and inspired texts.

The third speaker Julie Exline is a professor of psychology and spoke about the psychological reasons why people believe in god. She said that professors of psychology are generally less religious than the general population and until quite recently have shied away from research into religion. She herself has done a lot of research on what makes some people become angry with god (personal tragedy or widespread suffering) and how they deal with it. For some it is enough to cause them to become nonbelievers.

In my remarks, I said that my personal history with religion as I grew up was entirely positive, no anger with god or religion at all. So why did I become an atheist? It was almost entirely intellectual, simply because I found science and religion to be irreconcilable and thus felt forced to choose between them and the choice was intellectually simple, although the emotional hurdle of relinquishing strongly held religious beliefs was formidable. I said that the only way that science could be reconciled with religion is if the latter is drained of all supernatural elements and became just a set of rituals and practices similar to those found in any other social grouping.

I tried to shoot down the NOMA-like suggestion that is often advocated by some who duck the question of the existence of god and instead say that religions have value because they provide the basis for morality. I said that there was no reason to privilege religious texts over all the other sources that provide moral insight, from the secular moral philosophers to great secular literature. The Bible and Koran and Baghavad Gita were just books among millions of other books, unless they were the word of god, which brought us back to the primacy of the question of whether a god existed and intervened in the world.

I said that I disagreed with Princehouse that it was somehow sad that students felt forced to choose between science and religion. We all have to choose on all manner of difficult and emotionally charged issues all the time. Students often grow up in homes where they are taught that women, other ethnic groups, and gays are inferior and then find out in college that others do not share these beliefs and are forced to choose. I see it as a good thing that they are forced to confront their misguided childhood beliefs. Why should the choice between science and religion be any different and avoided?

I also made the point that while I had tremendous respect for Gould as a scientist and a writer, his NOMA work (which he wrote up in a book called Rocks of Ages) was an incoherent mess. Similarly while Collins was also a very good scientist, his book The Language of God was terrible. (In 2008 I did a multi-part review of Collins’s book that can be read here.) I did not say it but I find it telling that when eminent scientists try to argue for the compatibility of science and religion, their usual sharpness seems to melt away.

I also made the obvious point that the fact that there were theologians who were supporters of science and scientists who were religious did not mean that science and religion were compatible. All it showed was that it was possible for a human being to hold two contradictory views simultaneously.

Looking back on any event, I always think that I could have said things better and other points that I could have made but on the whole I think it went fairly well. I was hindered by the fact that I did not want to monopolize the panel’s responses to questions. If any readers of this blog were in attendance, they may be able to give a more objective evaluation.

My discussions with religious folk have always finished with my saying I don’t believe in the supernatural. I watched the Jacob Bronowoski clip on PZ’s blog yesterday which said everything about values without invoking religion

http://youtu.be/j7br6ibK8ic

Great blog Mano! Thanks

Hi Dr. Singham -- I had the opportunity to attend (along with my cousin), and found the discussion very fascinating. I would also echo the sentiment that (I believe) Prof. Exline stated that she was very impressed with the sophistication of the undergraduates at the seminar. I am a Case alumnus, and now teach at Kent State… while I don’t want to disparage my own students, I think a seminar like this at my campus would be much different in terms of student participation. So I thought that was cool!

I also think Prof. Princehouse’s point about the “tragedy” of choosing between religion and science is not so much that students who begin do realize the contradiction between the two are forced to pick one or the other, it’s that those that choose science often imperil their relationships with family and community members. To us, it’s an easy choice, but think what Prof. Princehouse was getting at was that choosing to believe in scientific evidence and principles over religious dogma can alienate a young person from their support structure. At least that was my take on her comments -- so I guess I am a little more sympathetic to her point.

I wish I had a chance to come say hello after the panel, but unfortunately my cousin had to get back to work (I had the afternoon off, but I was his ride).

Sounds like it was an interesting talk, any chance these things could be recorded and put up on YouTube?

Personally, I think Science and Mathematics are religions 🙂

Firstly, how does the joke go? “If you define a religion as an irrational belief in the unprovable, then not only is mathematics a religion, but it’s the only one that can prove it.” I gather some people don’t agree, but the general consensus is that Godel’s incompleteness theorem means that the logical foundation for arithmetic is unprovable.

Now lets separate Science into Theoretical, and Experimental. Theoretical science is maths, and as such, is part of the same belief system as maths. Experimental Science -- well -- when did Science ever prove anything? So that’s a belief system too.

That leads me to the inescapable conclusion that maths and science are religions too. Although it is rational to believe in something that seems to work all the time…

Cheers,

Wol