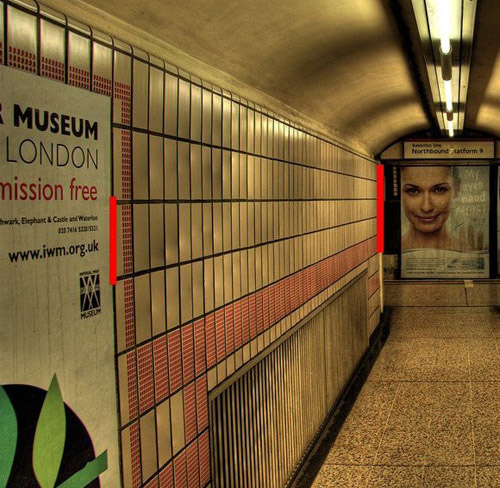

Look at this image and ask yourself which vertical red line would be longer if measured with a ruler on the photograph.

Phil Plait uses this image to give an explanation of the ‘moon illusion’, that refers to the phenomenon that a full moon that lies low on the horizon appears to be much larger than when it is high in the sky a few hours later, even though the measured size in the same. (To test this for yourself, roughly measure the diameter of the moon by keeping a pencil (or coin or any small object) at arms length straight in front of you and see how much of it corresponds to the diameter of the moon. Do this when the moon is low and again when it is high. It will be the same.)

There are a variety of explanations as to the origins of this illusion. One of the most popular is that this effect is due to the fact that when the moon is low, we gauge its size by comparing it with that of terrestrial objects like trees, buildings, etc. that it is close to or partially obscured by, whereas when it is high in the sky, we see it as it ‘really’ is. This is not particularly convincing because it does not really explain why the proximity of other objects makes something appear larger. It merely adds information that may or may not be relevant. But it is the usual explanation that is proffered.

But Plait says that this explanation is wrong, and that the effect is due to something called the Ponzo Illusion, which is that our brain figures size based on how far away we think an object is and it is the adjusted size that we ‘see’. If we think that something is far away, our brains make us ‘see’ it as larger than if we think it is nearby.

So what has all this got to do with the moon illusion? According to Plait, studies have repeatedly shown that the mental image that people have of the sky is not that of an inverted hemispherical bowl over our heads but is more like that of a bowl with a flattened bottom, a shallow dish really. This model of the sky may have been created by the fact that objects such as clouds and planes and birds look larger when they are directly overhead than when they are on the horizon, because in the latter situation they really are farther away. Hence our brain thinks of the sky directly above us as much closer than the sky near the horizon. Hence the moon near the horizon appears larger than when it is directly overhead because our brain thinks that the moon on the horizon is further away. It has nothing to do with proximity to buildings and trees.

Back to the above image of the red lines. The two red lines are actually the same length in the photograph. We think the one on the right looks longer because we know that if we had been actually in the London subway station where the photo was taken, it would be longer. The clues come from the wall tiles converging in the distance. The right line would be five times as long as the one on the left but appears reduced in size because it is farther away. So when we look at the photo, our brain automatically factors this in and makes the line on the right seem longer.

Is this the right explanation for the moon illusion? I don’t know, though it does seem plausible. It depends crucially on the assumption that we have a mental image of the sky as a shallow dish. I don’t know that I have consciously thought of it that way because I know that there is no such thing as ‘the sky’ except as an imaginary construct, and besides which I know that the moon’s ‘motion across the sky’ is itself an illusion caused by the Earth’s rotation and hence the distance to the moon cannot be changing. But that is a conscious modern view, based on scientific knowledge gleaned over the last few hundred years. It may be that what is hardwired in our brains are beliefs that date back to deep evolutionary times where the sky may have been believed to be a shallow dish and the moon tracked along it.

So although my conscious, scientific mind knows that the size of the moon must be the same on the horizon and overhead, it does not have the power to overrule the brain’s hardwiring that determines what I see. In other words, what I ‘see’ is not purely caused by physical visual input but is the result of unavoidable brain processing of that input over which I have little or no control. After all, even after measuring them and finding them equal, I still see the red line on the right as longer than the one on the left. I just can’t help it.

In reading about the Ponzo Illusion, I was reminded of something that lent support for it. In the book Your Inner Fish by Neil Shubin, whose team made the spectacular discovery of the fossil Tiktaalik in 2006, the author describes an experience in which they were looking for fossils in that part of Greenland that lies within the Arctic Circle. It is a flat, bleak, and barren region with no houses or trees or any of the familiar objects that normally give us a sense of distance or scale. The biggest danger to people in those areas is due to polar bears that can be highly dangerous. People who travel to those regions are given extensive training on how to avoid attracting them and defend themselves against them and warned to keep a sharp look out. As a result, he writes that after being dropped off at their site by plane,

The first thought is of polar bears. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve scanned the landscape looking for white specks that move… In our first week in the Arctic, one of the crew saw a moving white speck. It looked like a polar bear about a quarter mile away. We scrambled like Keystone Kops for our guns, flares, and whistles until we discovered that our bear was a white Arctic hare two hundred feet away. (p. 17)

Shubin writes that this error in perception was caused by anxiety making them see things. It is true that they were ‘seeing things’ but it may not have been due to anxiety, at least not exclusively. It could have been the Ponzo Illusion kicking in, with their brains misreading visual clues as to the distance of the hare from them.

I saw a “UFO” while driving once. It was about 150 ft in the air, the size of a U-haul truck, traveling maybe 50 mph in the opposite direction.

Then, as I came closer to it, the angle of the sunlight reflecting on it changed and revealed that it was: a small metal connector in the middle of a steel cable running across the street between two telephone poles. The lighting had previously made the cable blend in completely with the sky so that I only saw the metal connector. My mind had assumed that it was far away and therefore, must be large. And since I was moving one way, it created the illusion that it was moving in the opposite direction, if it was so high up.

If had been a better driver and paid attention to the road, I may have never seen what was really there. It’s amazing how our minds can fool us.

I find these sorts of posts fascinating, because of what they reveal about how our brains process data (and often by taking shortcuts, or relying on assumptions).

For more discussions on neuroscience and optical illusions, read the column by wife and husband team Diane Rogers-Ramachandran and Vilaynur S. Ramachandran in Scientific American Mind.

That’s interesting. I had always assumed, admittedly without any math or anything like that to back it up, that the moon appeared larger at the horizon because our atmosphere was creating some kind of lense affect which essentially magnified the moon. Now I feel silly.

You should not feel silly because this is a very common belief. Human beings are always trying to make sense of the world around them and creating their own theories as to why things are the way they are, using whatever knowledge they have at hand. Rather than being examples of silliness, arriving at such conclusions shows a thinking mind at work.

The problem is with those people who, when confronted with something that contradicts what they previously thought, do not investigate further to find out which makes more sense, but summarily reject the new information because it did not agree with what they already believed. That is the real silliness.

Fascinating!

This may also bear on something that’s bothered me about my own perception problems:

I can’t estimate heights very well. And I’m pretty sure this is normal. Looking at the top of a flag pole and trying to guess where I would have to stand on the ground to not get hit by it if it fell, I always *over* estimate the height. In other words, 12′ along the ground (2 people laying head to toe in series) seems a lot shorter length than 12′ vertical -- one person standing on another person’s head.

If the shallow bowl construct is valid, then I think it may be the source of these distance errors.

I think this is the right explanation. Something above you, let’s say a airplane, that is consistantly moving L to R, 1/4 of a mile above the surface appears to be going “across” the sky, not “around” the earth. So something moving around the earth,(excluding wobble for clarity) in this case the moon, on the illusary L to R model IS farther away than when it is directly above. I would also posit that even though the earth’s curvature limits your view beyond a crtitcal point, the effect of being on the surface looking up and around has “whole” feeling, like you’re looking off the edge of the earth in all directions (even though you know you”r not.

Another (admittedly anecdotal) supporting point for this interpretation is that some have reported that the illusion of the moon appearing larger on the horizon is just as pronounced when in the open ocean, where there are no visual cues on the horizon anyway.

I totally buy the dome thing. Look up at the sky on a cloudy night sometime and try to visualize the sky as a dome. Then think about how it would look if it really were hemispherical.

Our model of the sky tends to look a fair bit like this image, which is clearly not a hemisphere!

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_rf5j7tUYNdo/TUXaA2_-auI/AAAAAAAABrQ/R53cSNjickg/s400/domed%2Bcity1.JPG

I’m confused, shouldn’t we (relatively) underestimate the height of stuff when we’re close to it, and overestimate it when far away? Your pole example is then right at the transition of the two and I don’t know which way to think

Nice post, Mano! So I’m sorry that I must take issue with this passage that muddles evolution:

Maybe it’s not your intention, but you have written a Lamarckian evolution argument here. You are saying:

Individuals in population receive sensory input -> The population develops evolutionary adaptation for aggregate of sensory inputs -> Population evolves interpretation of single sensory input

While I think it would be more proper to say:

The population develops evolutionary adaptation for aggregate of sensory inputs -> An individual in population receives sensory input -> The individual creates a subconscious model interpreting the sensory input.

In other words, there was never a time when people spontaneously believed that the sky was oblate and this was inherited because it was advantageous. Instead our visual perception has evolved to process images to perceive depth in a certain, advantageous way. This way allows individuals to notice when sky objects are far away and when they are close. This spurs the creation of a model in the individual’s brain for the “shape” of the sky. This informs how images are processed when we see them, which in turn causes the optical illusion when something doesn’t conform to this model.

So evolving to see the sky this way is an epiphenomenon, and not a direct phenomenon. Many things may be ‘hardwired in’, but I think it has more to do with how the models are made in the individual than the model itself.

This is a very important distinction when talking about evolution and one that often gets confused!

You are quite right. My phrasing of the explanation was too terse and thus sloppy. Thanks!

When I looked at the picture, I didn’t think there was an optical illusion. Or maybe I sidestepped the issue by the way I measured the two red lines.

The nearest red line is about the height of one wall tile. The distant red line is the height of five wall tiles. So the distant red line is obviously much longer.

Well done, Jared. I can usually spot (forgivable) errors like this but I missed this one completely.

the lines were superimposed onto the photo after it was taken. Or are you snarking? Hmmmmm

At least refraction is a plausible and reasonable assumption. People who are willing to look for rational answers are more willing to admit when they are wrong.

.

I was given the “comparison to tall buildings” explanation as a kid, but after seeing the exact same phenomenon on the open ocean (I’m in the Navy), I couldn’t accept that anymore. I confess I also thought it might be a distortion effect caused by the atmosphere.

I guess my brain has been lying to me all these years! Thanks for the explanation!

I had also bought into the refraction idea. And surely refraction does take place and affect the view somehow? There is certainly colour refraction on occasions.

But the Ponzo illusion thing is fascinating, and warns me not to make assumptions!!! Thanks forthe great article.