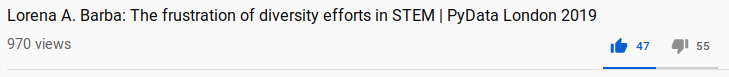

I was browsing YouTube videos on PyMC3, as one naturally does, when I happened to stumble on this gem.

Tech has spent millions of dollars in efforts to diversify workplaces. Despite this, it seems after each spell of progress, a series of retrograde events ensue. Anti-diversity manifestos, backlash to assertive hiring, and sexual misconduct scandals crop up every few months, sucking the air from every board room. This will be a digest of research, recent events, and pointers on women in STEM.

Lorena A. Barba really knows her stuff; the entire talk is a rapid-fire accounting of claims and counterclaims, aimed to directly appeal to the male techbros who need to hear it. There was a lot of new material in there, for me at least. I thought the only well-described matriarchies came from the African continent, but it turns out the Algonquin also fit that bill. Some digging turns up a rich mix of gender roles within First Nations peoples, most notably the Iroquois and Hopi. I was also depressed to hear that the R data analysis community is better at dealing with sexual harassment than the skeptic/atheist community.

But what really grabbed my ears was the section on gender quotas. I’ve long been a fan of them on logical grounds: if we truly believe the sexes are equal, then if we see unequal representation we know discrimination is happening. By forcing equality, we greatly reduce network effects where one gender can team up against the other. Worried about an increase in mediocrity? At worst that’s a temporary thing that disappears once the disadvantaged sex gets more experience, and at best the overall quality will actually go up. The research on quotas has advanced quite a bit since that old Skepchick post. Emphasis mine.

In 1993, Sweden’s Social Democratic Party centrally adopted a gender quota and imposed it on all the local branches of that party (…). Although their primary aim was to improve the representation of women, proponents of the quota observed that the reform had an impact on the competence of men. Inger Segelström (the chair of Social Democratic Women in Sweden (S-Kvinnor), 1995–2003) made this point succinctly in a personal communication:

At the time, our party’s quota policy of mandatory alternation of male and female names on all party lists became informally known as the crisis of the mediocre man…

We study the selection of municipal politicians in Sweden with regard to their competence, both theoretically and empirically. Moreover, we exploit the Social Democratic quota as a shock to municipal politics and ask how it altered the competence of that party’s elected politicians, men as well as women, and leaders as well as followers.

Besley, Timothy. “Gender Quotas and the Crisis of the Mediocre Man: Theory and Evidence from Sweden.” THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW 107, no. 8 (2017): 39.

We can explain this with the benefit of hindsight: if men can rely on the “old boy’s network” to keep them in power, they can afford to slack off. If other sexes cannot, they have to fight to earn their place. These are all social effects, though; if no sex holds a monopoly on operational competence in reality, the net result is a handful of brilliant women among a sea of iffy men. Gender quotas severely limit the social effects, effectively kicking out the mediocre men to make way for average women, and thus increase the average competence.

As tidy as that picture is, it’s wrong in one crucial detail. Emphasis again mine.

These estimates show that the overall effect mainly reflects an improvement in the selection of men. The coefficient in column 4 means that a 10-percentage-point larger quota bite (just below the cross-sectional average for all municipalities) raised the proportion of competent men by 4.4 percentage points. Given an average of 50 percent competent politicians in the average municipality (by definition, from the normalization), this corresponds to a 9 percent increase in the share of competent men.

For women, we obtain a negative coefficient in the regression specification without municipality trends, but a positive coefficient with trends. In neither case, however, is the estimate significantly different from zero, suggesting that the quota neither raised nor cut the share of competent women. This is interesting in view of the meritocratic critique of gender quotas, namely that raising the share of women through a quota must necessarily come at the price of lower competence among women.

Increasing the number of women does not also increase the number of incompetent women. When you introduce a quota, apparently, everyone works harder to justify being there. The only people truly hurt by gender quotas are mediocre men who rely on the Peter Principle.

Alas, if that YouTube like ratio is any indication, there’s a lot of them out there.

Alas, if that YouTube like ratio is any indication, there’s a lot of them out there.