[CONTENT WARNING: Sexual assault, trauma, abuse]

Put yourself in the shoes of a psychologist who specializes in recovered memories. As a quick refresher, “recovered memories” are events you deliberately forgot because of their traumatic nature, only to remember them later during counseling. The classic example of this is the Satanic Panic which gripped the US for a few decades; stories of horrific abuse suddenly appeared from all corners, leading to a lawsuits and even convictions.[1]

There’s just one problem: it’s terribly easy to manufacture a memory. You know of studies where participants tearfully discussed being lost in a mall as a child, even though you’ve talked with their parents and confirmed no such event took place.[2] You’ve seen people develop vivid memories of shaking hands with Bugs Bunny in Disneyland, even though the two have different corporate ownership.[3] People have even confessed to crimes they didn’t commit.[4] The longer the delay between the events and the recall, the more likely the memories of those events will be distorted or even false.[5]

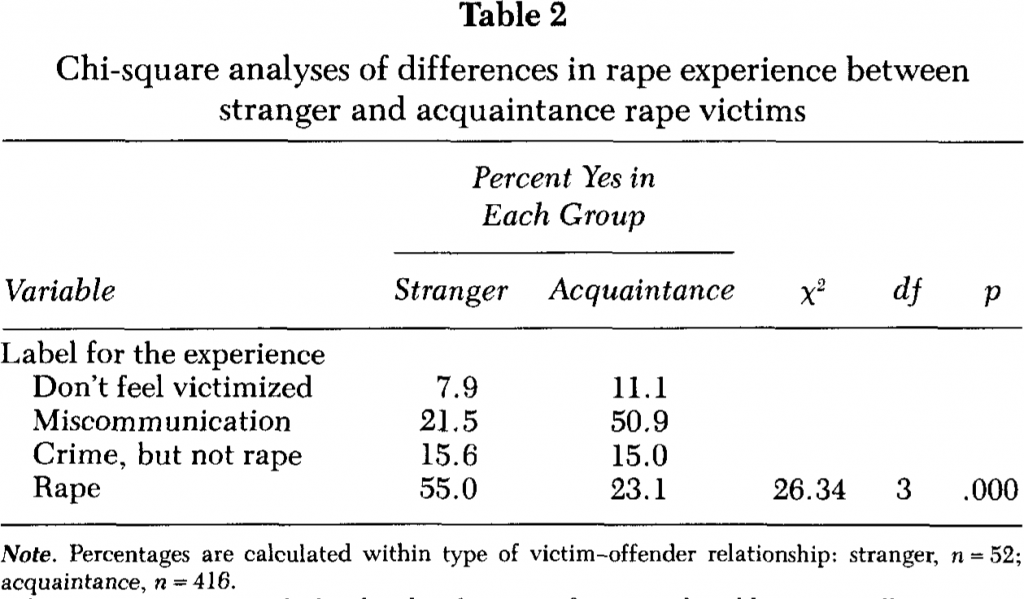

Snug in those shoes? Good, now tell me what you think of this table:

No doubt that’s setting off all sorts of alarm bells; how can something be considered “rape” if only 23% of the people who experience it label it as such?[6] You look closer, and also notice it’s quite common for people to come forward days, months, or even years after the events.

Among incidents where there was a delay of at least one day between when the crime occurred and when it was reported to police (representing 48% of sexual assault incidents), the median delay in reporting for sexual assault incidents was 25 days. This is about 12 times longer than the median delay in reporting (2 days) for physical assault incidents.

Over one-quarter (28%) of delayed reports of sexual assault were brought to the attention of police more than one year after the incident occurred. The same was true for 2% of physical assaults.[7]

Aha! This looks a lot like false memories, doesn’t it? Not if you look closer at the methodology behind that table:

Data on sexual victimization since the age of 14 were obtained through the use of the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss & Gidycz, 1985; Koss & Oros, 1982). […] The test-retest agreement rate between administrations one week apart was 93% (Koss & Gidycz, 1985). The accuracy and truthfulness of self-reports on the Sexual Experiences Survey have been investigated and significant correlations were found between a woman’s level of victimization based on self-report and her level of victimization based on responses related to an interviewer several months later, T = .73, p < .001 (Koss & Gidycz, 1985). Most importantly, only 3 % of the women (2/68) who reported experiences that met legal definitions of rape were judged to have misinterpreted questions or to have given answers that appeared to be false. […]

Women indicated whether or not they discussed the experience with anyone, reported it to the police, used a rape crisis center, considered suicide after the experience, and felt they needed counseling. Finally, victims indicated their label for the experience from among four choices: Did not feel victimized, felt I was a victim of serious miscommunication, felt I was a victim of a crime but not rape, and felt I was a rape victim.[6]

So right from the start, these women described an act which fit the legal definition of “rape.” Compare that with the process used to create false memories:

The McMartin and Wee Care Nursery cases are the most widely documented in the scientific community surrounding child eyewitness testimony. The repeated interviewing, the suggestive and coercive nature of the questioning and the length of the interrogations are among the factors in these cases that ultimately led to many false allegations. Indeed, the transcripts of interviews from these cases highlight how the dynamics of a conversation or interview can be so powerful as to lead children to produce graphic and believable statements of events that never happened to them.[8]

Single items on a survey are a far cry from “repeated interviewing” and “coercive … questioning.” This is a lot like the trolley problem, in that phrasing the same scenario differently can lead to different behaviors. It’s telling us there’s something special about sexual assault, or maybe traumatic events in general. This is a ripe area for research, and sure enough that has been done. Step out of your shoes for a bit, so we can dive into it.

A substantial number (84.4%) of the 77 sheltered battered women met the DSM-III-R criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder according to self-report. This percentage with possible PTSD is similar to that found for a sample of rape victims 6-8 weeks following the assault (80% of a sample of 30) by Kramer and Green (1990); and, for adult women seen clinically who had experienced incest as children (96% of a sample of 25) by Donaldson and Gardner (1985), even though considerably more time had elapsed since the trauma. This gives some indication that PTSD is relatively common for personal violence victims of battery, rape, and incest.

This sample of battered women easily met the DSM-RI-R criteria for intrusion, denial, and physical arousal.[9]

One common theme is denial: if you tell yourself the event never happened, maybe it didn’t? There’s good evidence this is maladaptive.[10] Take that original study; women who were raped by a stranger were more likely to call their event a rape than those who were raped by an acquaintance. If denial helped, you’d expect the former to have worse health outcomes than the latter, but instead that study found no statistical difference.[6] Nonetheless, it is a common response to trauma.

Denial is also helped along by “rape myths” which help excuse sexual assault. Maybe I was dressed the wrong way? Maybe I misunderstood the situation? A substantial number of people buy into them, and have for decades, so it would be no surprise if victims invoked them as well (and there’s evidence they do).[11] It’s also no surprise that other people buy into these myths, even those responsible for helping victims. “I didn’t come forward because I thought no-one would believe me” is a very common answer for staying silent, especially among male victims.[12]

According to the current [General Social Survey] on Victimization, the most common reasons for not reporting a sexual assault to police were that the victim felt the crime was minor and not worth taking the time to report (71%); it was handled informally (67%); and no one was harmed (63%). A number of victims voiced concerns regarding the justice system process, including not wanting the hassle of dealing with police (45%); the perception that police would have not considered the sexual assault important enough (43%); and that the offender would not be convicted or adequately punished (40%).[7]

Denial plays a major role in delaying coming forward, unsurprisingly, but there are other good reasons. As most sexual assaults are from someone you know, there’s a chance they’re a spouse, boss, or someone else with a fair bit of leverage over your life. Bring your story to the authorities, and they may use that leverage to punish you during an emotionally vulnerable time.

Sexual assault of children is also characterized by lengthy delays. According to the General Social Survey, the median delay between the sexual assault of a child and the reporting of the event to police was over 210 days, ten times higher than the median for non-children.[7] Part of this can be explained by the fact that someone else must learn of this incident before it is reported, as few children are capable of calling the police. Part of it is due to children’s unique response to sexual assault and abuse, however.

In the present study, 27 children’s CSA testimonies (including verification data showing that abuse had occurred) were analyzed. This allowed us to gain deeper insights into children’s testimonies about sexual abuse given in the context of police interviews. The present results showed that the bulk of the information provided by the children about the sexual abuse per se consisted of details about neutral information, and only 1 in 10 details actually concerned sexual information. Furthermore, the children in the present study were highly avoidant and frequently denied sexual abusive acts (i.e., verified acts). The present study together with previous research (e.g., Leander et al., 2005, 2007, 2008; Sjöberg & Lindblad, 2002a; Svedin & Back, 2003) indicates that many sexually abused children are reluctant to report about the sexual abuse, perhaps due to complicating emotional factors such as shame, guilt, fear of negative consequences, and use of defense mechanisms such as denial. It is of great importance to highlight the finding about children’s fragmentary reports, as the detail criterion is one of the most important reliability criteria in the Swedish Courts (recommendations from the Swedish Supreme Court) (Gregow, 1996).[13]

Speaking of memory, human memory doesn’t behave like computer memory: when you remember something from the past, you’re partially recreating your state of mind at that time. Recovering from a traumatic event involves re-experiencing it repeatedly, gradually trying to blunt its emotional impact. Similarly, coming forward with your story means recalling it multiple times, possibly in front of a hostile or insensitive audience. Not surprisingly, this creates a barrier for coming forward, which only subsides after some time to heal.

As suggested above, traumatic events also create different memory patterns, too.

Theories of PTSD have linked re-experiencing symptoms to more pervasive disturbances in autobiographical memory for the trauma (Brewin, Dalgleish, & Joseph, 1996; Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Foa, Steketee, & Rothbaum, 1989). The symptoms of PTSD include an “inability to recall an important aspect of the trauma” (American Psychiatric Association, 1994, p.428), and research suggests that intentional recall of traumatic experiences is impaired relative to recall of nontraumatic events (Byrne, Hyman, & Scott, 2001; Tromp, Koss, Figueredo, & Tharan, 1995). Clinically, trauma-exposed individuals may recall some aspects of the trauma with exceptional clarity, but the overall memory structure is often confused, with uncertainty relating to the sequence of events and important aspects of the trauma that cannot be recalled at all. There is preliminary evidence that the degree of such disorganization is related to the development of PTSD (Amir, Stafford, Freshman, & Foa, 1998; Gray & Lombardo, 2001; Murray, Ehlers, & Mayou, 2002) and acute stress disorder (Harvey & Bryant, 1999).[14]

That was quite the science dump, so let’s summarize: the scientific literature on sexual assault and trauma suggests that denial is common, as are delays in coming forward; memory tends to be more fragmentary and unreliable from traumatic events; and these effects are stronger in children. Put back on those shoes, though; notice that a researcher that specializes in recovered memories, with no knowledge of that literature, would conclude that a person coming forward with a fragmentary story of abuse from their childhood was likely experiencing a false memory.

We’ve got two different interpretations of the same evidence! In theory, the resolution is fairly easy: if there are signs of “repeated interviewing, the suggestive and coercive nature of the questioning and the length of the interrogations,” you can start to tip the scales towards away from “sexual abuse” to “false memory of sexual abuse.” Even then, abuse is common while “repeated interviewing” is rare, so our priors should be weighted towards “sexual abuse.” It takes a lot of knowledge of both literatures to accurately tease them apart, and a clear and unbiased approach.

Is that the case with the current Sandusky controversy? Let’s save that for part two, because damn is this post getting long …

[1] Clancy, Susan A., Daniel L. Schacter, Richard J. McNally, and Roger K. Pitman. “False Recognition in Women Reporting Recovered Memories of Sexual Abuse.” Psychological Science 11, no. 1 (2000): 26–31.

[2] Loftus, Elizabeth F. “Lost in the Mall: Misrepresentations and Misunderstandings.” Ethics & Behavior 9, no. 1 (1999): 51–60.

[3] Braun, Kathryn A., Rhiannon Ellis, and Elizabeth F. Loftus. “Make My Memory: How Advertising Can Change Our Memories of the Past.” Psychology & Marketing 19, no. 1 (2002): 1–23.

[4] Henkel, Linda A., and Kimberly J. Coffman. “Memory Distortions in Coerced False Confessions: A Source Monitoring Framework Analysis.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 18, no. 5 (2004): 567–588.

[5] Loftus, Elizabeth F., David G. Miller, and Helen J. Burns. “Semantic Integration of Verbal Information into a Visual Memory.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory 4, no. 1 (1978): 19.

[6] Koss, Mary P., Thomas E. Dinero, Cynthia A. Seibel, and Susan L. Cox. “Stranger and Acquaintance Rape: Are There Differences in the Victim’s Experience?” Psychology of Women Quarterly 12, no. 1 (1988): 1–24.

[7] Rotenberg, Cristine. “Police-Reported Sexual Assaults in Canada, 2009 to 2014: A Statistical Profile.” Juristat: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, 2017.

[8] Howe, Mark L., and Lauren M. Knott. “The Fallibility of Memory in Judicial Processes: Lessons from the Past and Their Modern Consequences.” Memory 23, no. 5 (July 4, 2015): 633–56.

[9] Kemp, Anita, Edna I. Rawlings, and Bonnie L. Green. “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Battered Women: A Shelter Sample.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 4, no. 1 (January 1, 1991): 137–48.

[10] Roth, Susan, Kathy Wayland, and Mary Woolsey. “Victimization History and Victim-Assailant Relationship as Factors in Recovery from Sexual Assault.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 3, no. 1 (1990): 169–180.

[11] Peterson, Zoë D., and Charlene L. Muehlenhard. “Was It Rape? The Function of Women’s Rape Myth Acceptance and Definitions of Sex in Labeling Their Own Experiences.” Sex Roles 51, no. 3–4 (2004): 129–144.

[12] Elliott, Diana M., Doris S. Mok, and John Briere. “Adult Sexual Assault: Prevalence, Symptomatology, and Sex Differences in the General Population.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 17, no. 3 (2004): 203–211.

[13] Leander, Lina. “Police Interviews with Child Sexual Abuse Victims: Patterns of Reporting, Avoidance and Denial.” Child Abuse & Neglect 34, no. 3 (March 1, 2010): 192–205.

[14] Halligan, Sarah L., Tanja Michael, David M. Clark, and Anke Ehlers. “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Following Assault: The Role of Cognitive Processing, Trauma Memory, and Appraisals.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 71, no. 3 (2003): 419–31.