How would a skeptic determine whether or not an area of study was legit? The obvious route would be to study up on the core premises of that field, recording citations as you go; map out how they are connected to one another and supported by the evidence, looking for weak spots; then write a series of articles sharing those findings.

What they wouldn’t do is generate a fake paper purporting to be from that field of study but deliberately mangling the terminology, submit it to a low-ranked and obscure journal for peer review, have it rejected from that journal, based on feedback then submit it to an second journal that was semi-shady and even more obscure, have it published, then parade that around as if it meant something.

Alas, it seems the Skeptic movement has no idea how basic skepticism works. Self-proclaimed “skeptics” Peter Boghossian and James Lindsay took the second route, and were cheered on by Michael Shermer, Richard Dawkins, Jerry Coyne, Steven Pinker, and other people calling themselves skeptics. A million other people have pointed and laughed at them, so I won’t bother joining in.

But no-one seems to have brought up the first route. Let’s do a sketch of actual skepticism, then, and see how well gender studies holds up.

What’s Claimed?

Right off the bat, we hit a problem: most researchers or advocates in gender studies do not have a consensus sex or gender model.

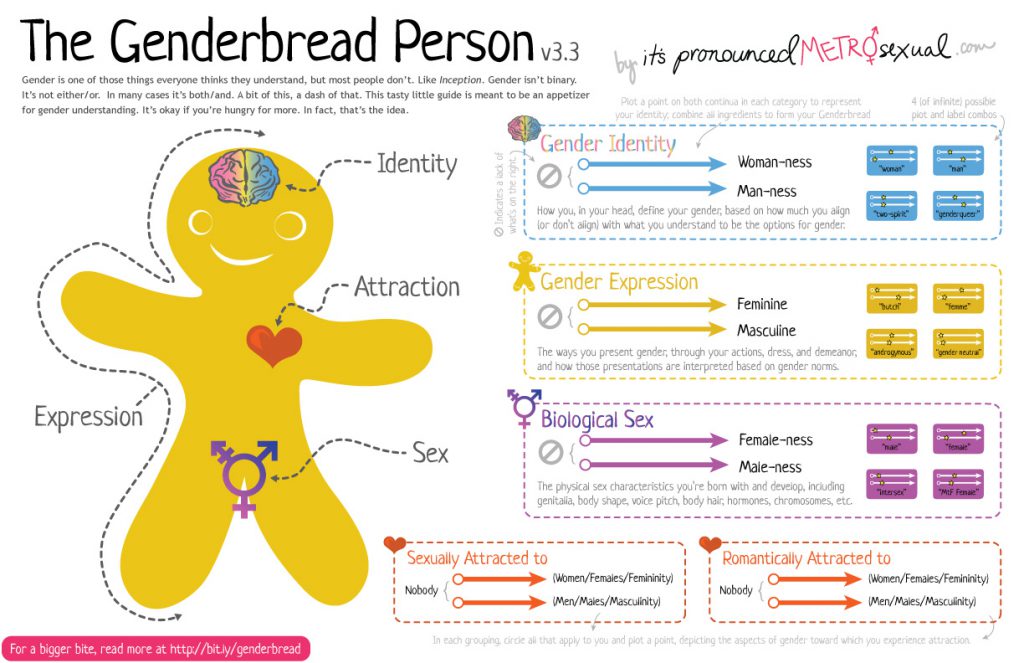

This is one of the more popular explainers for gender floating out on the web. Rather than focus on the details, however, I’d like you to note this graphic is labeled “version 3.3”. In other words, Sam Killermann has tweaked and revised it three times over. It also conflicts with the Gender Unicorn, which has a categorical approach to “biological sex” and adds “other genders,” and it no longer embraces the idea of a spectrum thus contradicting a lot of other models. Confront Killermann on this, and I bet they’d shrug their shoulders and start crafting another model.

The model isn’t all that important. Instead, gender studies has reached a consensus on an axiom and a corollary: the two-sex, two-gender model is an oversimplification, and that sex/gender are complicated. Hence why models of sex or gender continually fail, the complexity almost guarantees exceptions to your rules.

There’s a strong parallel here to agnostic atheism’s “lack of belief” posture, as this flips the burden of proof. Critiquing the consensus of gender studies means asserting a positive statement, that the binarist model is correct, while the defense merely needs to swat down those arguments without advancing any of its own.

Nothing Fails Like Binarism

A single counter-example is sufficient to refute a universal rule. To take a classic example, I can show “all swans are white” is a false statement by finding a single black swan. If someone came along and said “well yeah, but most swans are white, so we can still say that all swans are white,” you’d think of them as delusional or in denial.

Well, I can point to four people who do not fit into the two-sex two-gender model. Ergo, that model cannot be true in all cases, and the critique of gender studies fails after a thirty second Google search.

When most people are confronted with this, they invoke a three-sex model (male, female, and “other/defective”) but call it two-sex in order to preserve their delusion. That so few people notice the contradiction is a testament to how hard the binary model is hammered into us.

But Where’s the SCIENCE?!

Another popular dodge is to argue that merely saying you don’t fit into the binary isn’t enough; if it wasn’t in peer-reviewed research, it can’t be true. This is no less silly. Do I need to publish a paper about the continent of Africa to say it exists? Or my computer? If you doubt me, browse Retraction Watch for a spell.

Once you’ve come back, go look at the peer-reviewed research which suggests gender is more complicated than a simple binary.

At times, the prevailing answers were almost as simple as Gray’s suggestion that the sexes come from different planets. At other times, and increasingly so today, the answers concerning the why of men’s and women’s experiences and actions have involved complex multifaceted frameworks.

Ashmore, Richard D., and Andrea D. Sewell. “Sex/Gender and the Individual.” In Advanced Personality, edited by David F. Barone, Michel Hersen, and Vincent B. Van Hasselt, 377–408. The Plenum Series in Social/Clinical Psychology. Springer US, 1998. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-8580-4_16.

Correlational findings with the three scales (self-ratings) suggest that sex-specific behaviors tend to be mutually exclusive while male- and female-valued behaviors form a dualism and are actually positively rather than negatively correlated. Additional analyses showed that individuals with nontraditional sex role attitudes or personality trait organization (especially cross-sex typing) were somewhat less conventionally sex typed in their behaviors and interests than were those with traditional attitudes or sex-typed personality traits. However, these relationships tended to be small, suggesting a general independence of sex role traits, attitudes, and behaviors.

Orlofsky, Jacob L. “Relationship between Sex Role Attitudes and Personality Traits and the Sex Role Behavior Scale-1: A New Measure of Masculine and Feminine Role Behaviors and Interests.” Journal of Personality 40, no. 5 (May 1981): 927–40.

Women’s scores on the BSRI-M and PAQ-M (masculine) scales have increased steadily over time (r’s = .74 and .43, respectively). Women’s BSRI-F and PAQ-F (feminine) scale scores do not correlate with year. Men’s BSRI-M scores show a weaker positive relationship with year of administration (r = .47). The effect size for sex differences on the BSRI-M has also changed over time, showing a significant decrease over the twenty-year period. The results suggest that cultural change and environment may affect individual personalities; these changes in BSRI and PAQ means demonstrate women’s increased endorsement of masculine-stereotyped traits and men’s continued nonendorsement of feminine-stereotyped traits.

Twenge, Jean M. “Changes in Masculine and Feminine Traits over Time: A Meta-Analysis.” Sex Roles 36, no. 5–6 (March 1, 1997): 305–25. doi:10.1007/BF02766650.

Male (n = 95) and female (n = 221) college students were given 2 measures of gender-related personality traits, the Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI) and the Personal Attributes Questionnaire, and 3 measures of sex role attitudes. Correlations between the personality and the attitude measures were traced to responses to the pair of negatively correlated BSRI items, masculine and feminine, thus confirming a multifactorial approach to gender, as opposed to a unifactorial gender schema theory.

Spence, Janet T. “Gender-Related Traits and Gender Ideology: Evidence for a Multifactorial Theory.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64, no. 4 (1993): 624.

Oh sorry, you didn’t know that gender studies has been a science for over four decades? You thought it was just an invention of Tumblr, rather than a mad scramble by scientists to catch up with philosophers? Tsk, that’s what you get for pretending to be a skeptic instead of doing your homework.

I Hate Reading

One final objection is that field-specific jargon is hard to understand. Boghossian and Lindsay seem to think it follows that the jargon is therefore meaningless bafflegab. I’d hate to see what they’d think of a modern physics paper; jargon offers precise definitions and less typing to communicate your ideas, and while it can quickly become opaque to lay people jargon is a necessity for serious science.

But let’s roll with the punch, and look outside of journals for evidence that’s aimed at a lay reader.

In Sexing the Body, Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality Fausto-Sterling attempts to answer two questions: How is knowledge about the body gendered? And, how gender and sexuality become somatic facts? In other words, she passionately and with impressive intellectual clarity demonstrates how in regards to human sexuality the social becomes material. She takes a broad, interdisciplinary perspective in examining this process of gender embodiment. Her goal is to demonstrate not only how the categories (men/women) humans use to describe other humans become embodied in those to whom they refer, but also how these categories are not reflect ed in reality. She argues that labeling someone a man or a woman is solely a social decision. «We may use scientific knowledge to help us make the decision, but only our beliefs about gender – not science – can define our sex» (p. 3) and consistently throughout the book she shows how gender beliefs affect what kinds of knowledge are produced about sex, sexual behaviors, and ultimately gender.

Gober, Greta. “Sexing the Body Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality.” Humana.Mente Journal of Philosophical Studies, 2012, Vol. 22, 175–187

Making Sex is an ambitious investigation of Western scientific conceptions of sexual difference. A historian by profession, Laqueur locates the major conceptual divide in the late eighteenth century when, as he puts it, “a biology of cosmic hierarchy gave way to a biology of incommensurability, anchored in the body, in which the relationship of men to women, like that of apples to oranges, was not given as one of equality or inequality but rather of difference” (207). He claims that the ancients and their immediate heirs—unlike us—saw sexual difference as a set of relatively unimportant differences of degree within “the one-sex body.” According to this model, female sexual organs were perfectly homologous to male ones, only inside out; and bodily fluids—semen, blood, milk—were mostly “fungible” and composed of the same basic matter. The model didn’t imply equality; woman was a lesser man, just not a thing wholly different in kind.

Altman, Meryl, and Keith Nightenhelser. “Making Sex (Review).” Postmodern Culture 2, no. 3 (January 5, 1992). doi:10.1353/pmc.1992.0027.

In Delusions of Gender the psychologist Cordelia Fine exposes the bad science, the ridiculous arguments and the persistent biases that blind us to the ways we ourselves enforce the gender stereotypes we think we are trying to overcome. […]

Most studies about people’s ways of thinking and behaving find no differences between men and women, but these fail to spark the interest of publishers and languish in the file drawer. The oversimplified models of gender and genes that then prevail allow gender culture to be passed down from generation to generation, as though it were all in the genes. Gender, however, is in the mind, fixed in place by the way we store information.

Mental schema organise complex experiences into types of things so that we can process data efficiently, allowing us, for example, to recognise something as a chair without having to notice every detail. This efficiency comes at a cost, because when we automatically categorise experience we fail to question our assumptions. Fine draws together research that shows people who pride themselves on their lack of bias persist in making stereotypical associations just below the threshold of consciousness.

Everyone works together to re-inforce social and cultural environments that soft-wire the circuits of the brain as male or female, so that we have no idea what men and women might become if we were truly free from bias.

Apter, Terri. “Delusions of Gender: The Real Science Behind Sex Differences by Cordelia Fine.” The Guardian, October 11, 2010, sec. Books.

Have At ‘r, “Skeptics”

You want to refute the field of gender studies? I’ve just sketched out the challenges you face on a philosophical level, and pointed you to the studies and books you need to refute. Have fun! If you need me I’ll be over here, laughing.

[HJH 2017-05-21: Added more links, minor grammar tweaks.]

[HJH 2017-05-22: Missed Steven Pinker’s Tweet. Also, this Skeptic fail may have gone mainstream:

Boghossian and Lindsay likely did damage to the cultural movements that they have helped to build, namely “new atheism” and the skeptic community. As far as I can tell, neither of them knows much about gender studies, despite their confident and even haughty claims about the deep theoretical flaws of that discipline. As a skeptic myself, I am cautious about the constellation of cognitive biases to which our evolved brains are perpetually susceptible, including motivated reasoning, confirmation bias, disconfirmation bias, overconfidence and belief perseverance. That is partly why, as a general rule, if one wants to criticize a topic X, one should at the very least know enough about X to convince true experts in the relevant field that one is competent about X. This gets at what Brian Caplan calls the “ideological Turing test.” If you can’t pass this test, there’s a good chance you don’t know enough about the topic to offer a serious, one might even say cogent, critique.

Boghossian and Lindsay pretty clearly don’t pass that test. Their main claim to relevant knowledge in gender studies seems to be citations from Wikipedia and mockingly retweeting abstracts that they, as non-experts, find funny — which is rather like Sarah Palin’s mocking of scientists for studying fruit flies or claiming that Obamacare would entail “death panels.” This kind of unscholarly engagement has rather predictably led to a sizable backlash from serious scholars on social media who have noted that the skeptic community can sometimes be anything but skeptical about its own ignorance and ideological commitments.

When the scientists you claim to worship are saying your behavior is unscientific, maaaaybe you should take a hard look at yourself.]