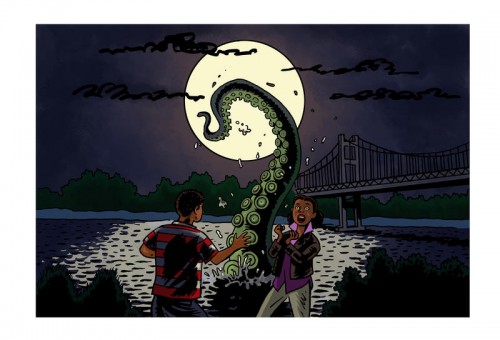

Except…the text is disturbing. It’s on the wrong side of the continent. Read this story of a common occurrence around Puget Sound.

Douglass Brown was 15 when he saw a giant tentacle emerge from Puget Sound.

He was in Tacoma, walking down the beach with a girl he liked. Then he looked out at the water.

“I see this arm come out of the water. It was 10, 15 feet in the air,” Brown says. “It looked like an octopus or something like that, and I just took off running.”

I can so imagine walking along the beach with my girl when I was that young, and enjoying the aquatic wildlife. Except that I can’t imagine running — that’s the part where you hold each other a little closer, and sigh romantically.

(Also, I think the “10, 15 feet” part is a gross exaggeration. “Inches,” maybe. But then, one does tend to inflate in those situations.)