I found this claim by Mark Armitage that had determined that a triceratops fossil was only a few thousand years old to be ridiculous. He has a defender, Jay Wile, who disagrees with me. He has two main points.

First, I said that carbon dating a dinosaur fossil is absurd — the 14C levels will be too low to get a reliable ratio. Wile thinks that you can, and that being able to cite a number makes it true.

Well, had Dr. Myers bothered to click on the link given in my post, he would have seen that an age was reported: 41,010 ± 220 years. As I state in that link, this is well within the accepted range of carbon-14 dating, and it is younger than many other carbon-14 dates published in the literature. In addition, the process used to make the sample ready for dating has been spelled out in the peer-reviewed literature, and it is designed to free the sample of all contamination except for carbon that comes from the original fossil. Now as I said in my original post, it’s possible that the reading comes from contamination. However, I find that unlikely, given the process used on the sample, the cellular evidence that Armitage found, and the fact that such carbon-14 dates are common in all manner of fossils that are supposedly millions of years old or older.

There are two sources of 14C we have to be concerned with. The bulk of it is cosmogenic, formed in the upper atmosphere from cosmic ray bombardments of ordinary, stable 14N. This 14C decays at a geologically rapid rate, with a half-life of 5730 years. Living things respire and tend to equilibrate their 14C levels with the environment. Another source, though, is the radioactive decay of other elements that generate high energy particles that can also bang into atoms to generate unstable radioactive isotopes. This is a much rarer event, though, so objects that are dead and buried and isolated from the atmosphere tend to equilibrate to a much lower concentration of 14C.

In carbon dating, the 14C to 12C ratio is measured. If it’s close to that of the atmosphere, it was recently exchanging carbon with the atmosphere. If it’s somewhere above the level of dead carbon buried deep in rocks (which has a non-zero level of 14C), it’s older, and we can estimate how much older from the ratio. You can always calculate a ratio. You can always measure a date. However, it will hit a ceiling of about 50,000 years, because of the limits of precision and because the ratio can converge to a value indistinguishable from the background level of 14C. Date a carbon sample that’s a hundred thousand years old; it will return an age of 50,000 years. Carbon date a chunk of coal from the Carboniferous, 300 million years ago, and it will return an age of 50,000 years.

That an “age” was reported is meaningless. An age of 40,000 years means that about 7 14C half-lives had passed, or that less than 1% of the atmospheric levels of 14C were present in the sample. Wile doesn’t understand this at all. He doesn’t seem to comprehend that there could be another source of 14C than from equilibration with the atmosphere. He thinks it is significant that ancient carbon can have non-zero amounts of 14C.

However, creation scientists have carbon-dated fossils, diamonds, and coal that are all supposed to be millions of years old. Nevertheless, they all have detectable amounts of carbon-14 in them. For example, this study shows detectable levels of carbon-14 in a range of carbon-containing materials that are supposedly 1-500 million years old. Surprisingly, the study includes diamonds from several different locations! Another study showed that fossil ammonites and wood from a lower Cretaceous formation, which is supposed to be 112-120 million years old, also have detectable levels of carbon-14 in them. If these studies are accurate, they show that there is something wrong with the old-earth view: Either carbon dating is not the reliable tool it is thought to be for “recent” dating, or the fossils and materials that are supposed to be millions of years old are not really that old. Of course, both options could also be true.

Or that there are underground sources of radioactive decay that can generate low levels of 14C, and that Jay Wile doesn’t understand basic principles of radiometric dating.

Wile also dismisses the possibility of an inclusion of recent biological material in the sample that might skew the date earlier, which is unjustifiable. Armitage himself writes about Soft, moist, muddy material can be seen surrounding pores of bone vessels on inner horn surfaces

and rootlets penetrating lower, interior surface

of samples where he claims to spot intact Triceratops cells.

But contamination can’t possibly be a confounding problem, oh no.

The second main point Wile makes is that gosh, those cells sure look like osteocytes, which have a distinctive shape with many branching processes. How would osteocytes have gotten in there?

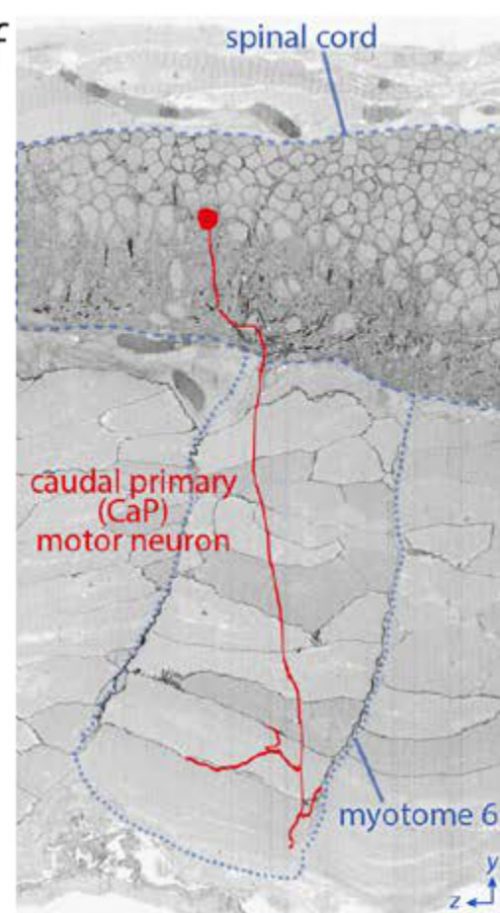

Armitage did not compromise his own results. He simply wrote truthfully about his fossil. In addition, anyone with a basic understanding of histology would know why plant roots, fungal hyphae, and insect remains do not compromise his results in any way. Based on all the visual evidence, the cells he found are osteocytes. They are not only the shape and size one expects from osteocytes, they have the filipodial extensions that are characteristic of osteocytes. They also have the cell-to-cell junctions one expects in groups of osteocytes. Thus, they cannot be the result of contamination, since plants, fungi, and insects do not have osteocytes.

My answer to that is…I don’t know. It’s weird. And Armitage doesn’t know either, and everything he says about the sample is incompatible with these being intact, preserved osteocytes.

The fact that any soft tissues were present in this heavily fossilized horn specimen would suggest a selective fossilization process, or a sequestration of certain deep tissues as a result of the deep mineralization of the outer dinosaur bone as described by Schweitzer et al. (2007b). As described previously, however, the horn was not desiccated when recovered and actually had a muddy matrix deeply embedded within it, which became evident when the horn fractured. Additionally, in the selected pieces of this horn that were processed, soft tissues seemed to be restricted to narrow slivers or voids within the highly vascular bone, but further work is needed to fully characterize those portions of the horn that contained soft material. It is unclear why these narrow areas resisted permineralization and retained a soft and pliable nature. Nevertheless it is apparent that certain areas of the horn were only lightly impacted by the degradation that accompanied infiltration by matrix and microbial activity. If these elastic sheets of reddish brown soft tissues are biofilm remains, there is still no good explanation of how microorganisms could have replicated the fine structure of osteocyte filipodia and their internal microstructures resembling cellular organelles. Filipodial processes show no evidence of crystallization as do the fractured vessels and some filipodial processes taper elegantly to 500 nm widths.

So…

-

The tissue is not isolated or protected in any way. It’s wet, unmineralized, and filled with a “muddy matrix”. Some of the soft tissues, the “vessels”, are crystallized.

-

The “osteocytes”, though, are perfectly preserved down to the level of organelles, ultrastructural junctions, and delicate processes.

Doesn’t anyone else have a problem with this? I’ve had to struggle with fixative cocktails to get good preservation of single-cell levels of detail; I’ve had animal tissue bathed in a soothing, perfectly balanced medium under my microscope, and seen bacterial infections turn them into disintegrating, collapsing blobs of blebbed out fragments of decaying cells within minutes.

Yet somehow Armitage finds picture-perfect “osteocytes” in tissues that have been soaking in mud, perforated by plant roots, and presumably have been lying there rotting since, by his measure, some time around the Great Flood, a few thousand years ago.

I’m just curious. As an experiment, if we killed a cow and then left it to rot in a damp field for just a month, would that be a good way to make useful histological samples of bone tissue?

How about if we left it there for a year? Or 40,000 years?

The Schweitzer papers on preserved cells in dinosaur bone at least demonstrate careful technique to minimize contamination and artifacts. They also don’t include comments that reveal the author doesn’t understand the basic principles of radiometric dating. The Armitage papers, on the other hand, are sloppy, get improbable results, and reveal a lot of biased reasoning.

I don’t know how cells that look like osteocytes got there, but I’m very suspicious.