I am so confused…but then science is often confusing. I was reading this article in Science magazine that went against my impressions and biases.

For years, scientists have been warning of a precipitous drop in insect numbers worldwide, driven largely by deforestation, pesticide use, and other human activities. But the first study to survey insect populations on a continental scale—based on radar data typically used to study weather patterns—finds no evidence of widespread decline, at least over a recent 10-year period. Instead, the research—published this week in Global Change Biology—suggests bug numbers tend to be sensitive to the severity of winter weather, with warmer winters posing a problem.

What, no decline? But I’ve seen a dramatic decline here in western Minnesota! Could I be wrong? Maybe. My perspective is narrow and local, and I’ve been looking at a small number of species, just spiders, that I’ve assumed would be a good proxy for overall insect number. I could be totally off, misled by a local variation that fit what I expected to see.

So I read the source paper. First surprise: the title doesn’t say there is no evidence of decline, but rather “Systematic Continental Scale Monitoring by Weather Surveillance Radar Shows Fewer Insects Above Warming Landscapes in the United States“. So there is evidence of decline in areas that show signs of warming. The abstract complicates matters further.

Anthropogenic change is predicted to result in widespread declines in insect abundance, but assessing long-term trends is challenging due to the scarcity of systematically collected time series measurements across large spatial scales. We develop a novel continental-scale dataset using a nationwide network of radars in the United States to generate a 10-year time series of daily aerial insect density and assess temporal trends. We do not find evidence of a continental-scale net decline in insect density over the 10-year period included in this study; instead we find a mosaic of increasing and declining trends at the landscape scale. This spatial variation in density trends is associated with climatic drivers, where areas with warmer winters experience greater declines in insect density and areas with cooling winter trends see increases in density. Winter warming has a stronger negative effect on density at higher latitudes. After assessing temporal trends, we also use the 10-year dataset and atmospheric variables to model insect aerial abundance, finding that on a typical summer day approximately a hundred trillion (1014) flying insects are present in the airspace, representing millions of tons of aerial biomass. Our results provide the first continental-scale quantification of insect density and its response to anthropogenic warming and demonstrate the utility of weather surveillance radar to provide large-scale monitoring of insect abundance.

Right away, I have reservations. If my observations are insufficient because I’m looking at too few species in one locale, this study is using one technique with low resolution on a continent wide scale and one could argue that it could be equally insufficient and misleading. It is data, though, and should be part of any analysis of the problem. Let’s not pretend that their sampling method doesn’t incorporate its own systematic biases. It’s only going to detect flying insects that exhibit swarming behavior, and they’re only looking at daytime numbers. It’s a correlational study that associates declines with only temperatures, but I’d suggest that those other factors (deforestation, pesticide use, and other human activities) are so ubiquitous and difficult to measure discretely that they’d disappear in the analysis.

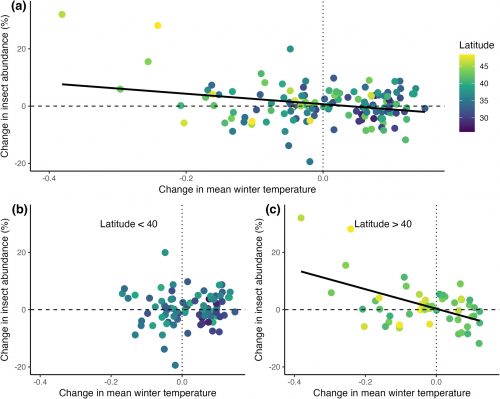

Also, their own data does show evidence of a decline…in latitudes above 40°.

Temporal pattern of change in insect density as a function of change in winter temperature. (a) 10-year trend in day-flying insect density as a function of the change in local mean winter temperature, colored by site latitude. (b) Temporal trend as a function of winter temperature at latitudes ≤ 40°. (c) Temporal trend as a function of winter temperature at latitudes > 40°. Fitted lines are derived from a least-squares linear regression on percentage change in insect density. Linear model with change in mean winter temperature, interaction with latitude, and longitude explains 18% of variation in insect declines.

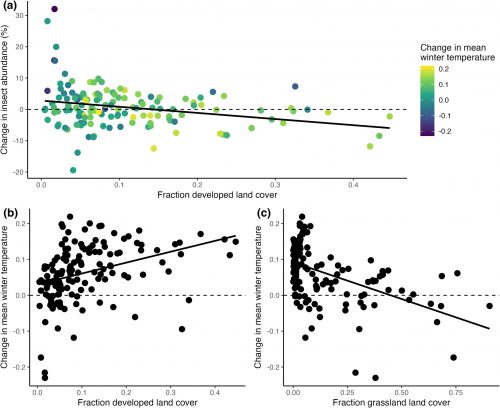

They also see some interesting variations, like the effect of land development on the sensitivity of populations to change.

Temporal pattern of change in insect density as a function of developed land cover. (a) 10-year trend in day-flying insect density as a function of the fraction developed land cover in the landscape, colored by the change in mean winter temperature. Line is given by LM. (b) Change in mean winter temperature as a function of the fraction developed land cover. Line is given by LM, correlation coefficient = 0.37 p < 0.0001. (c) Change in mean winter temperature as a function of the fraction grassland in the landscape. Line is given by LM, correlation coefficient = −0.54, p < 0.0001.

Insect populations are actually increasing over developed areas? I’d like to know the baselines on that — this is a study over a short timescale of ten years, and who knows, minor fluctuations over areas where the population has already been decimated by development might appear as a larger percentage change. I also wonder if we might be seeing the effect of adaptation or invasive species on those areas.

I’d also be concerned that native grasslands are hurting.

They do argue that anthropogenic stressors are having a serious effect.

Although we do not observe continental scale declines, the spatial patterns of abundance trends identified in this study can pinpoint potential stressors or drivers of insect declines. Declines in aerial insect density were stronger in regions that experienced increasing winter temperatures. During overwintering, warming can decrease fitness by releasing organisms from cold-induced dormancy, thereby increasing metabolic rates, and depleting energy reserves. Winter warming may also result in increased mortality due to phenological mismatches with resources, and may extend the activity period for natural enemies and reduce pathogen die-off during the winter season. Negative effects of winter warming on insect abundance in temperate regions have been shown in local surveys of beetles, butterflies, and arthropods generally, indicating that winter is a particularly sensitive season for temperate ectotherms.

Sensitivity to winter warming varies across populations and is likely more common in cooler climates where thermal seasonality is strong. Our results show a negative effect of winter warming at high latitudes, with no effect at latitudes below 40°. This latitudinal interaction between winter warming and aerial insect density aligns with theory suggesting that climate warming will have the strongest effect on cool-adapted arthropods. For example, metabolic costs are greater at high latitudes, affecting organisms’ cold tolerance and resulting in greater risks of energy depletion if winters become warmer under global change. Experimental warming has shown that high elevation gall wasp species experience greater decreases in survival and fecundity than those from lower latitudes. These stronger responses from high latitude insects to winter warming are particularly concerning because the magnitude of warming under climate change also increases with latitude.

I definitely live in an area with harsh winters, which would explain how I have a strong impression of declines on the basis of local observations. I don’t understand, though, how the work in this paper can be used to minimize the changes in insect populations. I’m also a little concerned that it’s being used to endorse a hands-off analysis of relatively coarse radar data over expecting entomologists to get their hands dirty and get up close with the organisms.