Well, ain’t this a kick in the pants. Here’s a compilation of failed concepts in psychology, for example, the oft-mentioned Stanford Prison Experiment is a badly done botch, the Pygmalion effect is small and inconsistent, the Milgram experiment is full of experimental errors, etc., etc., etc. It’s rather depressing.

As someone who spends a lot of time online, though, I was relieved to learn that’s not responsible for feeling low.

Lots of screen-time is not strongly associated with low wellbeing; it explains about as much of teen sadness as eating potatoes, 0.35%.

So you’re saying I should cut potatoes out of my diet, then?

The impression I get is that a lot of the popular ideas that have emerged out of psychology arise not because the experimenter is rigorous and cautious, but because they either conform to conventional wisdom or are surprisingly contrary. There’s also something analogous to the TED Talk effect, where people are convinced more by the certainty of the presentation of the story than by the data. I’m beginning to develop my own rubric for assessing psychological claims: if it’s so simple that it gets condensed down to just the investigator’s name, it’s probably shoddy work with questionable validity. I’m calling it the Myers Rule.

The author of the list says something I think is worth keeping in mind, though. They’re talking about the concept of Ego Depletion, which has a substantial wiki page.

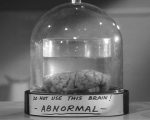

It’s 3500 words, not including the Criticism section. It is rich with talk of moderators, physiological mechanisms, and practical upshots for the layman. And it is quite possible that the whole lot of it is a phantom, a giant mistake. For small effect sizes, we can’t tell the difference. Even people quite a bit smarter than us can’t.

If I wander around an old bookshop, I can run my fingers over sophisticated theories of ectoplasm, kundalini, past lives, numerology, clairvoyance, alchemy. Some were written by brilliant people who also discovered real things, whose minds worked, damnit.

We are so good at explaining that we can explain things which aren’t there. We have made many whole libraries and entire fields without the slightest correspondence to anything. Except our deadly ingenuity.

Human brains are so easily diddled by grand simplifications (religion, for instance) that they’ll then turn phantasms into sweeping, detailed rules for existence. It’s all superstitious behavior in the psychological sense — we’re all searching for patterns so obsessively that if they aren’t there, our minds start imposing them on the world.

I’m so glad I’m not working in psychology. Evolution and developmental biology would never cultivate popular errors. Wait — but those sciences are studied by human minds, which are clearly kind of squirrely.

Easy there, you’re starting to sound like Jeff Goldbloom in Jurassic park. Not necessarily an insult BTW.

Hence, why I’m extremely reticent about blindly watching TED Talks.

Lest I waste time on a new wrongness, Ala the vitamin C debacle that still haunts us today.

“OH, use vitamin C, it cures everything and is an antioxidant”.

So is manganese. But I don’t eat fucking batteries and call them a panacea.

The brain is an excellent pattern recognition engine. It’ll happily find pattern everywhere and gin up false patterns when only noise is present.

Realizing that mitigates against incorrectly hearing Space Ghost telling you secrets when listening to a white noise source.

I gave up on TED talks after watching a run of poor videos that had been given a lot of thumbs up, culminating in an especially pernicious one on how police can tell if you’re lying — it was nothing more than long-debunked body language theories expressed with extraordinary certainty and a lot of tv-anchor charisma but zero evidence or recognition of limitations. What particularly irked me is not just that it was so scientifically unsound, but that it played into myths about policing that are known to lead to false convictions.

I love the idea of TED talks and there are many really great ones — but they clearly needed to put a lot more effort into curation.

What about looking at pictures of potatoes on a screen?

(I’m still calling cryptocurrencies Dunning-Krugerrand though. That’s too good a pun to give up).

True, but good, rigorous science accepts that and makes a good faith effort to work around it and eliminate it as a factor. Hence the use of controls, levels of statistical significance, double-blind procedures, etc. It’s the best we have.

Stanley Milgram is known for a couple of experiments, one regarding people’s willingness to obey authority even to the point of administering painful electric shocks to strangers when so ordered, and the other regarding the “six degrees of separation” phenomenon. Neither really stands up to scrutiny, although the six degrees phenomenon has also had more mathematical analyses showing how the length of the path between two randomly chosen nodes in a network plunges as new, random links are forged.

Of course the electric shock experiment used actors pretending to be shocked in lieu of the real thing and may have been weak in other ways. Interestingly, there are real-world examples of people blindly following authority. Netflix currently has a documentary called Don’t Pick Up The Phone detailing a series of cases of people basically committing sexual assault on the orders of a voice over the telephone identifying as a police officer.

As for psychology, I have long felt that at its best, it’s a soft science; at its worst, it’s Just So Stories.

And the brain? Don’t get me started on that kludgy old contraption. Although I see no reason to insult squirrels.

@3 Chris- There was something in the news recently about people having their 911 calls used against them in court if they “sound guilty.”

Matt G @ #6 — Perhaps you mean Tracy Harpster, deputy police chief from Dayton, OH, who claims he can tell someone is guilty from their voice. His “method” has been used to convict…wrongfully…a few people.

Before becoming an atheist I belonged to several liberal congregations within the conservative tradition that I was raised in. While the doctrine didn’t make sense, the people seemed at least as smart as me. I still read the blogs of a couple of those pastors and professors, obsessed with the question of why such thoughtful, well-informed, articulate people sincerely and mindfully believe such a load of hooey. The idea that their highly active brains generate spurious explanations makes more sense than the usual explanations for religiosity – some combination of brainwashed, dim, protecting a job, thoughtlessly following a tradition or a desire to feel special.

Any thoughts on whether the research of Daniel Kahnemann and Amos Tversky fails along the similar lines? I’ve found their reports thought provoking, and Kahnemann’s books interesting, but I’m not sure how well they hold up.

The Stanford Prison Experiment at least led to a good film (German language, but you can get it with subtitles) : Das Experiment.

Human brains like grand simplifications – first religions, now political ideologies. I think I have been inoculated against that, but there is always peer pressure to consider.

It helps to have a wide and diverse social network.

.

It also helps to have a different language – harmful memes (like Ayn Rand rubbish) can be translated but is not quite as powerful.

(And if you are not an arabic speaker you will know of the koran through translations. Without the poetry component, it is obvious it is rubbish just as it is obvious the bible is rubbish.)

For specific examples, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nobel_disease

Having been trained in psychology and cognitive science, I have grown frustrated with my fields as we really tend to go out of our way to ignore how much variation there is in the human condition. So much work that we do seeks to reduce human experience to means and medians, and when you do that you can set up any research design to give you basically any result you want. For one of the most absurd examples, see Daryl Bem’s work on precognition. The most remarkable thing about that research was how everything he did lives up to the very low standard of rigor expected in the discipline, and it is a real shame that the lesson we learned as a result of Bem’s shenanigans wasn’t that we all need to reexamine what constitutes methodological and analytical rigor and how those should correspond to theoretical coherence, but instead some weird lip service sentiments about replication.

My flippant take is that the most profound and well-accepted discovery in the field of psychology is the placebo effect, and researchers still have much work to do to explore and understand the subtleties and implications of that generalized concept—as applies not only to their subjects but to themselves, and not only to particular experiments to much larger scale and longer term intellectual projects—before they go on to bigger questions.

@charley:

Sadly, we have lots of evidence showing that intelligent people are often better at finding ways to rationalize their own pre-existing beliefs rather than using that intelligence to see that they might be wrong.

jenorafeuer, sure, they’re better at doing that, but they’re similarly better at realising what they’re doing and so reappraising.

I think it’s more about circumstance and motivation and temperament than about intelligence; or: yes, the smarter one is, the more one can rationalise any given belief, but similarly, the better one can realise they are but rationalising.

End of the day, beyond a certain (minimal) degree of mental competence, what matters is character. Lack of intellectual honesty is the factor, far as I’m concerned, other things being equal.

PS

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.”

Richard Feynman

@ 16 John Morales

Hahahaha. This is person who – literally yesterday – pretended a comment calling him “so white” was a reference to actual skin tone. And proceeded to describe his skin tone, showing he knew damn well the person had never seen it, and could not possibly have been commenting on it.

If Pharyngula had an award for “least intellectually honest commenter”, it would undoubtedly and indisputably be called the “Morales award”. X-D

The sheer nerve is almost breathtaking.

John Morales @ #17 — Because of cognitive ease, we…as in all of us…are fooling ourselves almost all the time. At least that’s the result of the research of Daniel Kahnemann and Amos Tversky. The notion that humans behave rationally is greatly over rated. This also applies to human enterprises like markets, which is why Kahnemann was awarded the Noble in economics instead of medicine or some other science award. However, I don’t know if Kahnemann’s research stands up to scrutiny any better than other research in the “soft” science fields.

So…yeah. Ego Depletion. Back in the day, my dissertation was partly based upon it. I used a Stroop task to “create” it. While it was but 1 manipulation, I still found a statistically significant main effect where I expected it. My hypothesis: there’s no special mechanism for mental energy depletion. It’s all just straight-up fatigue. Working your brain is a physical event and the results should be physical.