One of my worries, as I have benefited from choosing a career in the sciences as the world goes mad for practical educations, is that I see all the non-STEM fields being neglected by a capitalist perspective on universities. This is not good. Balance in all things, please, and we should support the entirety of knowledge, not just the bits that give us missiles and antibiotics (although, at the same time, I think students in non-STEM fields would benefit from a little more math and science — liberal arts educations are currently a bit asymmetric, with science students expected to broaden their horizons while the history majors get to ignore calculus and physics).

So here’s a historian taking the “STEM Bros” to task, entirely justifiably.

The last two decades have seen the rise of the Irritating STEM Bro.™ Two well-known examples are Neil deGrasse Tyson and Steven Pinker: Great Men from Important Science Backgrounds who blithely talk and write about the history of their topic as if they are expertly qualified polymaths. Both use the word ‘medieval’ pejoratively, and see the history of science as an inexorable, teleological march of progress from the fantastic Classical Period to the Terrible Medieval Dark Ages and then woo Renaissance! And then things gradually getting better and better until hurrah! We are enlightened and clever in the 21st century!

Quite simply, though, this is insulting, ahistorical nonsense. The problem, which Irritating STEM Bros™ don’t understand – or more likely don’t want to acknowledge – is that our modern categories of ‘science’, ‘religion’, and ‘magic’ do not map in any meaningful way onto the medieval period. So let’s first examine this problem of categories.

The whole thing is entertaining, but this bit made me laugh.

Psychologist Steven Pinker’s 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined has as its central thesis the idea that violence has declined over time, and that we now live in the most peaceful era yet. This is, he tells us, due to five main developments: the monopolisation on the use of force by the judiciary stemming from the rise of the modern nation-state (as expressed in Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan of the mid-17th century); commerce, feminisation, cosmopolitanism and the ‘escalator of reason’.

It’s this last factor, which is of most interest here, this ‘escalator of reason’ which says that we now apply ‘rationality’ to human affairs. This, Pinker tells us, means there’s less violence in modern society than there was because we’re more rational. And he’s not shy to use the Awful Irrational Medieval Dark Ages as a counterpoint to the Brilliant Post-Enlightenment Modern Times of Awesome.

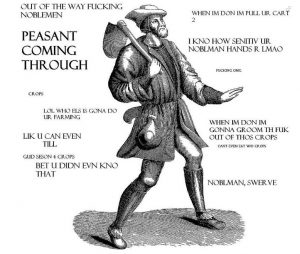

Why laugh? Because I have eyes and ears and I live in 21st century United States of America, in a red county, in a town that is full of churches, and I can look around and see all the “rationality”. 40% think a greedy, incompetent grifter was a great president, and about the same number think God created the Earth in a literal 6 days. I suspect that your typical medieval peasant wouldn’t have been quite so delusional. Not that they wouldn’t have had their own follies, but sheesh — people are still people, and haven’t become noticeably more intelligent in the last thousand years.

For an amusing example of the “increase of rationality” since the Middle Ages, the first definitive historical record of the Shroud of Turin is from a catholic bishop in 1390 who wrote to the pope that he had investigated it and determined it to be a forgery.

The medievals believed in God, sure, but they believed in a God who had created a universe that could by and large be understood by human reason.

This has always very much been my schtick. For ages it seemed like I was the only one who banged on about this self-serving modern scientist’s model of historical progress. It’s nice that someone else is saying it now.

The thing is, of course, that the model is entirely in keeping with the self-serving view of the superiority of the modern age that has been with us since the actual Renaissance. Indeed, it would not be going too far beyond the mark to say that the whole cultural thrust of the Renaissance was to lionise the ancient and the modern (seen as a rebirth of the ancient) by demonising the newly created idea of the medieval inbetween.

The Pinkers of the world are largely oblivious to the fact that all they are doing is perpetuating a model of intellectual history conceived over five hundred years ago as a conscious attempt to stroke the egos of its conceivers.

#2 History and sociology major here. The ideas of inerrancy and infallibility of the bible are relatively recent concepts.

If people were “uneducated and unscienced” a thousand years ago, how did they advance farming, develop trades like cartwrights and drapers? English is full of nursery rhymes and mnemonics because pre-1600 and pre-Gutenberg, that’s how people learnt and transmitted knowledge: by rhyme, memory and experience (“red skies at night, shepherd’s delight”, etc.). They had knowledge, they just didn’t have books and most were illiterate.

I grew up watching James Burke‘s “Connections” and “The Day The Universe Changed” and am glad of it. Burke demonstrated the links between history, science, politics, and society, showing that nothing happens in a vacuum, it’s all interconnected. Schools need to integrate their curriculum, not isolate.

“Connections” on the Internet Archive

From the article;

Tyson, Pinker, Krauss and others certainly do themselves favours; their shallow smugness gets them on chat shows and lecture tours, and sells books. And I’m sure it’s not just STEM fields that have suffered in the Age of the Glib Sound Bite.

The problem is that even if I assume Pinker is right and the world is getting better and better, it’s getting better at such a slow rate as to not do us any real good. Further, human ability to inflict catastrophe on itself and the rest of the planet through things like climate change, pollution and the like are quickly outpacing any enhanced moral sense that we need to do something about it. So if I had to lay any money on it, my bet would be that we destroy ourselves long before we advance to the point of actually cleaning up our own messes.

What??? Even when they tell us that there was a historical Jesus?

KG @ #7

“They” do? The historians I’ve read are very uncertain, even skeptical, about this “historical Jesus”.

To be fair Pinker sees the US as something of an anomaly compared to Scandinavia. I think one aspect he focused in on was the rise of opiate addiction, but perhaps also disgruntled white males, though that maybe more Enlightenment Now. He also counter-STEM sees value of fiction putting one into shoes of others which allegedly contributed to increase in empathy more recently. He loves Singer’s escalator metaphor which does have a point. And I think he has an appreciation for the value of most philosophy not shared by Tyson and others.

But it was his contretemps with literati Wieseltier that inspired Enlightenment Now.

KG @7: No, that’s when they become “so-called” experts with unexamined biases. Or something.

If you look at the audience when special guests speak at college, you will find scientists and engineers when the lecture is on liberal arts. But when the lecture is on science or engineering, the liberal arts people stay away.

Careful! If we start listening to historians, we might actually learn something from history, and then where would we be?

Not that the Romans weren’t capable engineers, but the civil engineers of the 19th and 20th centuries helped build water and sanitation systems that greatly improved human health and welfare, so in that respect STEM deserves credit. So does germ theory and how food has been made safer for consumption along with modern medicine and antibiotics and vaccines. Three cheers for science, engineering, and medicine!

@KG That’s when we declare that historians are “embedded in a culture that insists as a matter of dogma that Jesus was real,” and that we should ignore them.

Evidence?

Of course, lots of students take them in high school. I did. Leaving that aside, my impression was that my university wasn’t very unusual in terms of having those sorts of requirements. It was a good school, but in that respect it was pretty standard I think. This apparently wasn’t so common back in your day, but in the last few decades that has changed at least somewhat.

If you just want to argue that they “would benefit from a little more math and science,” then okay … it’s hard to argue with that. But if the non-STEM students are actually getting more than you thought they were, then maybe you should just be pleasantly surprised about that instead.

theworstelephant @ #14 — And it’s not just the Jesus story. From my reading, there are similar issues with the Hebrew/Jewish historical narrative that some people, particularly Christians, accept as historical fact while there’s evidence that much of it is fiction. And similar with the origin narrative of Islam.

robro @16: I thought theworstelephant was being sarcastic. But then my sarcasm detector has been a bit off lately.

@8 Robro: “The historians I’ve read ….”

Start reading qualified ones. Like the atheist Tim O’Neill.

Sure non-STEM students would benefit from more STEM. Just as STEM students would benefit from more history. More knowledge is never a bad thing, let’s not pitch complementary knowledge against each other.

It’s easy to frame this in a “Right Man For the Right Job”-setting, but I disagree. It should be about finding the right job for everyone. Society is supposed to serve man, not the other way around.

Rob Grigjanis — I thought that might be the case, but it’s so difficult to tell.

mnb0 — “Start reading qualified ones.” What makes you think the people I have read aren’t qualified? They seemed very qualified based on their biographies, degrees, and other reputation indicators, as well as their writings and methods of analysis.

Evidence? I teach at a university. I advise students. I am totally familiar with the requirements for graduation. Here, for instance, students are required to take one science course for their degree, and most take the “rocks for jocks” course. Meanwhile, they have to take a year of a foreign language, courses in history, English, and a range of other courses for breadth.

I think that’s a good thing. I’m not saying there isn’t a good reason to take courses outside the sciences, I’m saying there are also good reasons to expect higher standards in science requirements across the university.

(It’ll never happen.)

Because they don’t posit a historical Jesus, obviously!

No serious historian considers Jesus mythicism seriously. I’ve been told that over and over and over. And the reasons they don’t, and why the apparently-sound-if-maybe-not -quite-as-slam-dunk-as-their-proponents-think arguments in favor of it that I have read are wrong, are…um…well, actually I’ve never gotten even a semblance of an answer to that question. Maybe you’ll have better luck.

Pinker’s books are on my “read after retirement” list. My sense would be that he’s probably right about the decline of violence, but wrong about this particular cause. Mostly, the decline of large-scale violence seems related to modern tactics and weaponry changing the cost/benefit analysis for attempting to conquer one’s neighbor. Also, there is capitalism to blame: why conquer your neighbor for his resources when you can buy them instead?

PZ:

You don’t say? It’s only one of thousands in the country. I thought we were talking about all, most, or the very at least “many” of them.

It’s also the case that nobody else needs to take any serious music courses, unless it’s their major or minor. (And if they just need one “fine arts” course, say, then it may not be music at all. So much for “breadth.”) The point is, you’re sorely mistaken if you don’t think it’s the equivalent of “rocks for jocks.” So, you don’t have a good reason to make that a part of your comparison, because whatever asymmetry there may be, it’s not that.

(For the record, I never took a course in geology.)

I accept that and agree. I was disputing the statement that “history majors get to ignore calculus and physics.” Simply not true in my experience, which I readily admit only represents a limited perspective on liberal arts and sciences colleges in general.

edit: “at the very least”

Pinker weighed in on the Dr. Suess “cancellation” via Twitter. He’s a dope.

cr @24:

You know history majors who took undergrad calculus? I’ve only known a few history majors well enough to know (including my nephew), and none of them took calculus (or algebra; maybe general science) courses in undergrad. Maybe they were atypical?

I’m not a lecturer, but the ignorance of most people about their own bodies despite having done biology and/or personal health courses in school is something I find shocking. I think it would be enormously to their benefit for students of all types to know more about how their bodies work, even if only to the extent that they know where the major organs are so they know what is causing them pain or feeling different should that occur. I’m not expecting everyone to remember the Krebs cycle, but you at least ought to have an idea about which part of your body is behaving differently from normal, so you know whether it needs urgent attention or you can leave it a while to see if the problem resolves without medical intervention.

I don’t expect history majors to take calculus, as it’s not something that they’d get any use out of after graduation. Statistics, maybe.

calculus

If I recall from the olden days, in America there’s a standard undergraduate core of required courses designed for and shared by science majors and engineers: 3 semesters of calculus, 2 semesters for physics with calculus, and 2 semesters for inorganic chemistry with calculus — plus an additional semester of math and some science outside your field. I think biologists only needed one semester of calculus but had to take organic chem.

Liberal art students weren’t required to take any of that except for maybe college algebra. And at least for the ones I knew, they chose humanities specifically to avoid all that stuff. OTOH, I think that changes at the grad level, at least for the social/behavioral sciences.

I’d be curious to be updated on that. Also, it’s probably different in Australia, I’m curious about that too.

naturalistguy @29: Well, there’s history of science. But I can imagine other historians having to analyze large data sets as well, which could require more sophisticated methods than statistics sans calculus. Maybe they just use standardized software…

To clarify my work break rush post, Pinker in his Enlightenment Now chapter on happiness said this:

“Among the countries that punch below their wealth in happiness is the United States…But in 2015 the United States came in at thirteenth place among the world’s nations (trailing eight countries in Western Europe, three in the Commonwealth, and Israel), even though it had a higher average income than all of them but Norway and Switzerland…[huge skip]…Also, the United States has seen a greater rise in income inequality than the countries of Western Europe (chapter 9), and its growth in GDP may have been enjoyed by a smaller proportion of the populace.33 Speculating about American exceptionalism is an endlessly fascinating pastime, but whatever the reason, happyologists agree that the United States is an outlier from the global trend in subjective well-being.”

In another chapter on Inequality he said:

“To acknowledge that the lives of the lower and middle classes of developed countries have improved in recent decades is not to deny the formidable problems facing 21st-century economies. Though disposable income has increased, the pace of the increase is slow, and the resulting lack of consumer demand may be dragging down the economy as a whole.62 The hardships faced by one sector of the population—middle-aged, less-educated, non-urban white Americans—are real and tragic, manifested in higher rates of drug overdose (chapter 12) and suicide (chapter 18).”

In the Reason chapter he goes against the CATO talking points grain:

“… countries that combine free markets with more taxation, social spending, and regulation than the United States (such as Canada, New Zealand, and Western Europe) turn out to be not grim dystopias but rather pleasant places to live, and they trounce the United States in every measure of human flourishing, including crime, life expectancy, infant mortality, education, and happiness.”

I think I merged these distinctly made points in my fallible memory.

I can think of two magnificent science documentary series fronted by two great science communicators; Cosmos with Neill deGrasse Tyson and the BBC series Science and Islam with Jim al-Khalili. Full praise for their polished and professional presentation but if you work your way through the credits no doubt you will find them heavily packed with historians and liberal arts graduates who did the background research and script development and were almost certainly waist deep in the logistics of these huge undertakings

I started reading Pinker’s “Blank Slate” and I was hearing echoes of “The Bell Curve”. He then quoted Thomas Sowell and I realized going any further woud be a waste of time.

@22 I consider both of what I call “historcism” (Yeshua was an ordinary man, a Jewish apocalyptic preacher, and the Synoptic Gospels contain a historical core) and “semi-mythicism” (the Gospels are almost-entirely fictional. While there probably was a historical basis for the fanfics, we don’t know what Jesus was like) to be more likely than mythicism (Jesus never existed; in many scenarios the anonymous author of Mark invented the historical Jesus).

If the mythicists want to win me over, they should find an ancient manuscript of a super-early Christian text that has Jesus being 69crucified in a heavenly realm (the standard mythicist scenario) to override the evidence that the first Xtian author, Paul, thought that a historical Jesus indeed existed. So from, say, 10 BCE to 50 CE.

Mythicism is a positive claim that needs positive evidence to support it to be taken seriously. If there are no surviving “basal” (from the trunk of the Xtian religious tree) manuscripts– the earliest NT manuscript fragment is from the early second century– too bad. Historicism and semi-mythicism is a better explanation of the data we have, even though the arguments historians use to support a historical Jesus are not as slam-dunk as they believe.

How is someone 69crucified? Wait scratch that I don’t want my perverted mind-image confirmed. Brain bleach. Lots.

drawing your conclusion while taking your pick of the evidence is a thing for court rooms and trials not scientific inquiry.

uncle frogy

I’m a fan of Neil deGrasse Tyson. Sure, sometimes his Tweet timing is off hehe and Pluto 4 ever! but I like him. He’s a role model for me. I don’t have many of those.

I just finished a couple of books sited in the 1300s. The author of one, The Light Ages, makes the argument that there was real science in the middle ages. He writes about the astrolabe and the computations that were done using base 60 AND Roman numerals. The other book, a bio of English royal Henry IV, contains a story about a non-peasant who said out loud words to this effect “I just cannot believe the communion wafer turns into Jesus’ body in my mouth.” Of course, he was murdered in some horrible way by the state but I was amazed that somebody then got on record about how stupid a lot of (all?) religious beliefs are.