I’m only a 21st century Minnesotan, by which I mean I grew up on the West coast, lived on the East coast, and only made the trek to the Midwest when I was in my 40s, in the summer of 2000. One feature of the trip across Ohio and Illinois, up through Wisconsin along Lake Michigan, and across to Minnesota and the Mississippi that grossed out my kids was the bugs — the windshield splatter, and worst of all, the black cake of insect carcasses matting the grille of our truck at the end. In the years after we arrived, there were many times our car imitated a filter feeder on summer drives, sucking in a pathetic mass of dead mosquitos and mayflies, requiring a thorough hosing out to be presentable once again. We’d also see the weather radar on the TV, showing vast clouds of insect hatches rising from the rivers and lakes.

In recent years, though, almost imperceptibly, the population of insects has declined to the point where it’s unusual and noticeable when we splatter a few bugs on a drive across the state. Apparently, we also missed the genuinely remarkable swarms that sporadically blanketed the Midwest in the 1950s.

Through the middle of the 20th century, enormous summertime swarms of Hexagenia mayflies were a common sight across many of North America’s largest waterways. The immense scale of mayfly emergences made them a natural spectacle, and reports of the aquatic insects blanketing waterfront cities regularly filled newspaper headlines. Deep drifts of mayflies rendered streets impassable until snowplows could clear and grit roadways, and the dense swarms reduced visibility and inhibited water navigation, temporarily halting river transportation.

I regret not ever seeing that spectacle, although the locals don’t seem to — while I’ve heard many stories of fierce blizzards and massive snowfalls in the “old days”, no one has regaled me with tales of deep deposits of mayfly corpses. It’s a shame, I’d like to hear about it.

These stories do at least make an anecdotal impression that there has been a steep decline in the aquatic insect population. From a time when insect swarms could shut down travel in the mid-century, to my personal experience of running into major bug densities when I first arrived in Minnesota, to now only rarely hearing about scattered clouds of mayflies rising off the lakes, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that we have a problem here. The problem is…us.

…by 1970, these mass emergences had largely disappeared. The combination of increasing eutrophication from agricultural runoff, chronic hypoxia, hydrologic engineering, and environmental toxicity resulted in the disappearance of Hexagenia from many prominent midwestern waterways, with complete extirpation from the Western Lake Erie Basin and large segments of the Illinois, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers. After two decades of absence, targeted efforts in conservation and environmental protection led to the eventual recovery of Hexagenia populations and recolonization of major habitats in the early 1990s.

So there was a window of time where the numbers were even lower, and what I saw in 2000 was a resurgence? I’d say, from my subjective observations, that they’re in decline again, and what we need is more hard data on insect numbers over time. That’s what we’re getting from Stepanian and others, who recently published quantitative data on the emergence of mayflies across Lake Erie and the Upper Mississippi river, making calibrated measurements using weather radar. For instance, here’s a single emergence event smothering the entire western end of Lake Erie in a single night in June of 2018.

Macroscale phenomenology of a mayfly emergence over Lake Erie on the night of June 27, 2018 as observed by weather surveillance radar. (A) Radar snapshot at 01:56 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) depicting the initial ascent of mayflies from the lake surface surrounding the shorelines of Point Pelee, Pelee Island, and Kelleys Island. At this time, a total of 2.1 million mayflies are detected in the airspace. (B) Radar snapshot at 02:50 UTC showing the continuing ascent and downwind drift of mayflies across the lake to the southeast. Additional emerging mayfly plumes develop surrounding North, Middle, and South Bass Islands. Mayflies reaching the southern lakeshore rapidly descend out of the airspace. At this time, a total of 394 million mayflies are detected in the airspace. (C) Radar snapshot at 03:32 UTC. Emergence and ascent have largely terminated as mayflies continue to fly downwind toward the southern lakeshore. At this time, the aerial abundance reaches a maximum, with a total of 2.0 billion mayflies detected in the airspace. (D) Radar snapshot at 04:32 UTC. Most mayflies have already descended from the airspace as the trailing edge of the mayfly plume approaches the southern lakeshore. At this time, a total of 81 million mayflies are detected in the airspace. (Lower) The time series of aerial mayfly abundance during the emergence event. The mayfly numbers given in A–D are annotated as well as the time of local sunset.

Over two billion insects surging out of the water over the span of a few hours! That isn’t even the most impressive event: they report that a single event in Lake Erie can spawn 88 billion mayflies with a mass of over 3,000 tons; the upper reaches of the Mississippi might produce 3.25 billion insects weighing a total of 114 tons. These events represent a huge transfer of organic matter from the bottoms of lakes and streams to terrestrial environments. That’s a significant transfer of nutrients like phosphorus and sulfur to the land, and is clearly an important food source for many animals. The authors do an entertaining calculation of how many calories are in flux here.

Starting with the 104.49 calories contained in a single Hexagenia limbata, we multiply by the Lake Erie emergence (115 billion individuals) to get annual caloric content (12.016 trillion calories). We took the tree swallow (Tachycineta bicolor) as a model aerial insectivore that has been shown to rely on aquatic insect emergence for feeding fledglings during the nesting season. Dividing the total annual caloric content of the emergence (12.016 billion kcal) by the required 224 kcal to raise a nestling over the 15-d development period, we arrive at the total number of nestlings that can be supported by this food resource (53.6 million birds).

That matters! While I vaguely had the impression that mayfly numbers have declined in the 20 years I’ve lived here, that kind of loss has effects that ripple upwards through the populations of animals that live here. It’s too easy to obliviously trundle along, relieved that I’m not having to go to the car wash as often, and then at some point we notice that we’re not hearing as many songbirds, and the bats seem to be dying off, and the fishing isn’t quite as good anymore, and we finally wonder what’s going on…and it’s too late, because we didn’t stop to think that maybe life in the Midwest has been missing the tons of flying biomass that had been periodically deluging the environment with manna.

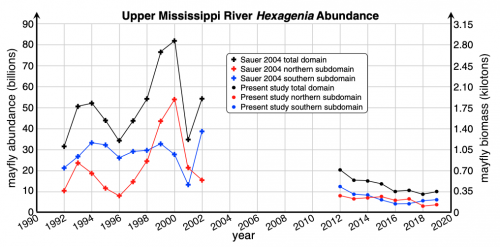

That’s one of the messages of this paper — that we have lost about half the mayfly biomass in recent decades, lost to poor management of fertilizers and excessive toxic chemicals in our most productive agricultural lands and just general neglect of wetlands. They’re measuring the disappearance of billions of insects.

Ongoing declines in Hexagenia mayfly abundance (individuals ×109) and biomass (tons ×103) on the Upper Mississippi River. Surveys of Hexagenia abundance over the Upper Mississippi River (black) as well as contributions from the northern (La Crosse, WI; red) and southern (Davenport, IA; blue) subdomains as measured by benthic sampling (crosses) and radar surveillance (circles).

It’s a slow, quiet catastrophe. We’re in the depths of winter right now, no mayflies in sight, but just yesterday I was out by our local river, the Pomme de Terre, where this is a typical view. It’s frozen over, with a foot or two of ice frosted with snow, but beneath all that is a busy ecosystem, with fish feeding on the aquatic insect larvae, and billions of mayfly larvae consuming algae and detritus, growing strong for the spring thaw and the summer breeding season, when they should leap into the air in eager swarms, filling the air with life.

But will they?

The Pomme de Terre river, near Morris, Minnesota, on 15 February 2020. There are mayflies there, you just can’t see them…yet.

Stepanian PM, Entrekin SA, Wainwright CE, Mirkovic D, Tank JL, Kelly JF (2020) Declines in an abundant aquatic insect, the burrowing mayfly, across major North American waterways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Feb 11;117(6):2987-2992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913598117.

I remember road trips in the Midwest as a kid, and the fireflies thick enough to make glowing rainbow smears on the windshield, and catching enough of them in a jar to read my comic books by. Last time I visited, I saw a whole 3 fireflies at once!

The Pomme de Terre river?!? Please tell me all the tributaries have names like Spud.

Well Rachel Carson did warn you of a silent spring ,maybe she should have mentioned a windscreen clear spring .

Some people have said that the reason insects don’t splatter so much on car windscreens is that cars are so aerodynamically designed they don’t hit .

I remember clouds of insects during spring through summer and children skating on lakes and ponds through at least the majority of winter.

Haven’t observed either for years, especially lakes and ponds frozen long enough to be thick enough to walk on, let alone skate on.

But, the chemophobic crowd has a solution, it’s roundup! All of it, as ice and bees (at least, to ascertain from an e-mail I received a few minutes ago) are obviously plants and killed by the defoliant!*

So, I’ve been worn down, I say, let the chemophobes get what they want, a chemical free continent! Only neutrons and electrons are allowed here, as protons being about runs the risk that chemistry could happen and that can’t be allowed.

While the moron brigade tries to figure out how to create Neutronium America, those with operational brains can address climate change and pollution.

*I received an e-mail that made tremendous mental leaps claiming bees are being poisoned because of almond milk, then jumping to “chemical cocktails” which seem to all be RoundUp! and that kills bees by blocking the shikimate pathway, which animals lack.

Note to self: Stop reading bullshit e-mails that make such leaps of idiocy.

I recall seeing the bodies of mayflies inches deep on store window sills in my small town on the Muskingum river during my teens.

It should be remarked that light pollution kills a lot of insects. Attracted by the light they are unable to reproduce. I think/hope that LED light is less offensive in this regard. Polarization (moonlight) should be investigated.

jack16

@davidc1: Recent studies suggest that the “windshield phenomenon” (Wikipedia has a page) my not be a thing. The Guardian recently report research in Europe that tested it, driving vintage cars on the same roads as new cars; the new cars splatted more insects than the old ones.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/feb/12/car-splatometer-tests-reveal-huge-decline-number-insects

Scary indeed.

@6 Thanks for that ,yes scary indeed .

what I fine so interesting is the more we look at the details of any species phenomena the more we find how interconnected it is with everything else . As in the decoupling post you can look at something in isolation but nothing exists in isolation. Like beavers in a watershed make the character of the forest and enable everything else to exist and much off it they they depend on, or the salmon who with their bodies and the help of all the animals who feed on them bring nutrients to the forests soil. You mess with one and you effect all. We have been flying blind.

I have never seen the mayfly swarm but I have seen the air quality in L.A. change for the better in the last few years and there does seem to be more wildlife about anecdotal I know but one grasps at straws when there is little else about.

uncle frogy