As you all know, 2023 has been off the charts, in terms of the global temperature. There have been record-breaking heatwaves and fires all over the northern hemisphere, but we’ve had the predictable chorus of “it’s always hot in the summer”. I don’t expect to persuade any of those people – they’re either wholly detached from reality, or they are being paid to help usher humanity to extinction. They are, however, a useful rhetorical device, and thanks to decades of relentless propaganda, there are still some who are uncertain about the facts of global warming, so in response to that bad-faith argument, I would like to direct your attention south of the Equator, to South America, which is currently in its winter, and has also been undergoing a record-breaking heatwave. From August 3rd:

Now should be South America’s bleak midwinter, but several parts of the continent are experiencing an extraordinary unseasonal heatwave that scientists believe offers a disturbing glimpse of a future of extreme weather.

Argentina’s riverside capital, Buenos Aires, this week recorded its hottest 1 August in 117 years.

Cindy Fernández, a weather bureau spokesperson, said her country was facing “a year of extreme heat”.

“Winter temperatures are way off the scale – not only in the central region where Buenos Aires is but also in the northern regions bordering Bolivia and Paraguay where temperatures reached between 37C (98.6F) and 39C (102.2F) this week.”

Hundreds of miles to the west, in Chile, temperatures rose even higher, towards 40C.

“July was the planet’s hottest month since records began and the Andes are now experiencing their own thermal ordeal,” announced the Santiago-based newspaper La Tercera. “Although we’re in winter, Chile is living through a little hell of its very own.”

Raúl Cordero, a climate expert from the University of Santiago, told the newspaper that as far as temperatures and rainfall were concerned, “Chile’s winter is disappearing”.

“It’s not surprising that temperature records are being set all over the world. Climate change ensures these records are broken more and more frequently,” Cordero said.

Parts of Paraguay, Bolivia and southern Brazil have also been baking in what extreme weather-watcher Maximiliano Herrera called “brutal” temperatures of almost 39C. “For at least five more days there won’t be any relief and we can’t rule out some 40s,” Herrera predicted on Twitter where he claimed the unusual winter heat was “rewriting all climatic books”.

“We are used to the heat in Paraguay, but the weather now makes it so hot we don’t leave the house,” said Ariel Mendoza, a 32-year-old car salesman in Paraguay’s capital Asunción, as the mercury there rose to 33C on Thursday.

Five years ago, winter in Paraguay made for chilly days, Mendoza pointed out. “But now it’s 30C-35C [86F-95F] in the winter due to climate change.”

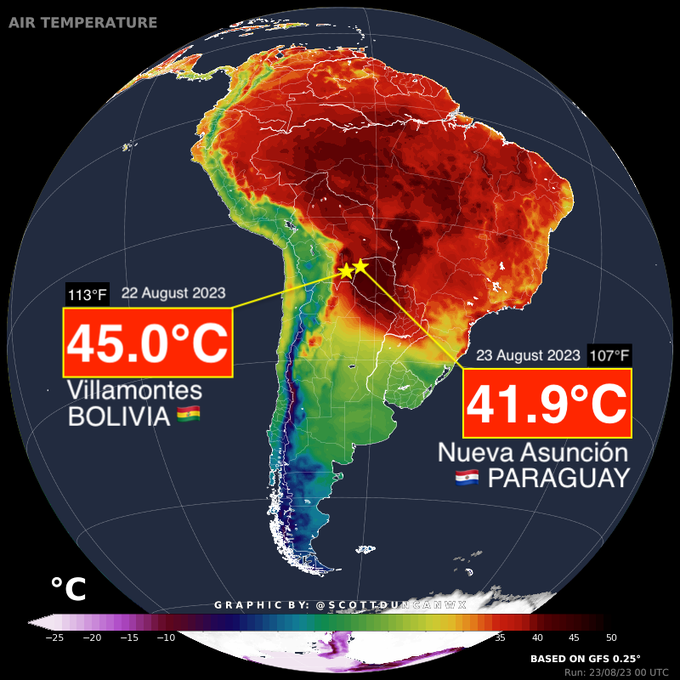

In a stunning turn of events, turning up the temperature of the whole planet, turns up the temperature of the whole planet. The heatwave isn’t over, either. Here’s a lovely map from just a few days ago:

The image is a heat map of South America, showing a deep red over Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, parts of Equador and Columbia. The Andes can be seen as a green stripe hugging the west coast, and turning blue towards the southern tip of the continent. Urugay and Argentina show green, outside the heat dome. Two markers show temperatures of 45°C/113°F in Villamontes, Bolivia on August 22nd, and 41.9°C/107.42°F in Vueva Asunción, Paraguay on August 23.

The running theme of this century will be that nowhere is safe. This isn’t because we didn’t already know that. It’s been clear for decades that a global rise in temperatures was happening, and that nowhere would be safe from the harm that would cause. Unfortunately, thanks to the corruption and propaganda I mentioned earlier, a lot of people still haven’t really internalized what is happening to our world.

Apparently, they needed to actually see it happen, to actually believe it, and so here we are.

I don’t really blame people who have been duped on this issue, so much as those who have spent and earned fortunes in duping them. Even so, it’s hard not to be angry at those who have spent decades fighting to make this world, with all its horrors, come to be, because they were so afraid of communism, or so hateful of minorities, that they could not see the bigger picture.

It is not just summer. It is global warming, and it is everywhere.