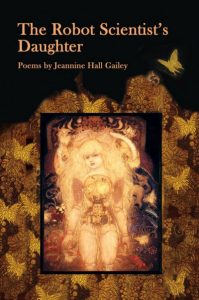

The Speculative Poets in Conversation Series features interviews with writers of science fiction and fantasy poetry about how their work addresses social justice issues. For the third post in the series, I spoke with poet Jeannine Hall Gailey about her 2015 collection, The Robot Scientist’s Daughter, published by Mayapple Press.

Jeannine Hall Gailey served as the second Poet Laureate of Redmond, Washington. She is the author of five books of poetry: Becoming the Villainess, She Returns to the Floating World, which was a finalist for the 2012 Eric Hoffer Montaigne Medal and a winner of a Florida Publishers Association Presidential Award for Poetry, Unexplained Fevers, The Robot Scientist’s Daughter, and her latest, winner of the Moon City Press Book Prize and SFPA’s Elgin Award, Field Guide to the End of the World. She’s also the author of PR for Poets: A Guidebook to Publicity and Marketing. She has a B.S. in Biology and an M.A. in English from the University of Cincinnati, as well as an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Pacific University. Her poems have been featured on NPR’s The Writer’s Almanac and on Verse Daily; two were included in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror. In 2007 she received a Washington State Artist Trust GAP Grant and in 2007 and 2011 a Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Prize.

Freethinking Ahead: In the collection, we see the character of the Robot Scientist’s Daughter as both of the community and yet outside of it. How did you initially conceive of her in respect to your intentions for the poems? Did your concept of her change over the course of the collection, especially in light of your personal connections to Oak Ridge National Laboratories and that of the research you did for the poems?

Jeannine Hall Gailey: The Robot Scientist’s Daughter is a mythological character who has  a lot in common with me, but isn’t actually me. I’ve always enjoyed writing persona poetry, and in this book, which is much more personal (and actually has first-person autobiographical poems in it) I thought it provided a little bit of fun and more potential for sci-fi experimentation inside the historical story of Oak Ridge and my own history living there.

a lot in common with me, but isn’t actually me. I’ve always enjoyed writing persona poetry, and in this book, which is much more personal (and actually has first-person autobiographical poems in it) I thought it provided a little bit of fun and more potential for sci-fi experimentation inside the historical story of Oak Ridge and my own history living there.

FTA: I’m curious about the theme of the perilous nature of the parent/child relationship in the collection: the dangerous offspring elements created in “Radon Daughters,” the wasps and swallows building nests from radioactive mud in “Hot Wasp Nest,” “The Girls Next Door” and their daughters, and, of course, the Robot Scientist and his daughter.

JHG: In this book, there is a definite sense of menace in terms of scientific “fathers” – I specifically reference some scientists who made what I consider unethical decisions when it came to their creations in nuclear science and of course, they carry the responsibility for the creation of the most devastating military weapon ever – the nuclear bomb. There’s a feeling that people in the nuclear era – and in Oak Ridge – trusted the government to tell them about the dangers nuclear experimentation exposed them to, and that trust was betrayed multiple times, in multiple ways, over the last fifty years. In environmental terms, the endangered babies of various animals raised in a toxic environment represented by own (and many other children from the area’s) damage from exposure to nuclear pollution – but I wanted to represent the damage this nuclear pollution does to the entire ecosystem, not just the human part of it.

FTA: You note in your introduction to the book that one of your reasons for writing the collection was to draw attention to the potential harms of nuclear research, particularly “that the half-life of the pollution from nuclear sites is longer than most human life spans.” The presence of the children in the collection, affected as they are by the pollution, seems to work in tension to the danger, however, as we see the children as a kind of emblem of some better possible future. What drove your choice to place them both within and as narrator(s) of the poems?

JHG: Children don’t have a choice about where they live, or what their parents do for a living, and yet, they are still exposed to dangers that they may or may not be aware of that can affect them for the rest of their lives, and even their children’s lives. Children can make decisions when they become adults about what they do about that exposure, whether they speak out against it, or keep their families (and their governments’) secrets for them. You can see the results of this now in young people in Japan who are much less tolerant of nuclear power and nuclear pollution after living through the disaster at Fukushima than perhaps previous generations have been. I hope this book raises some awareness about our own problems – still unfixed – in cities near the readers – not just Oak Ridge and Hanford, the sister “Atomic cities,” but many secret cities around our country. Anyone who talks about how “clean” nuclear energy is needs to be educated about the real dangers and the effects already around many rural (and some not-so-rural) areas in America.

FTA: Throughout the collection, you anchor the poems in the landscape around the ORNL with almost incantatory series of plants and animals, from “lilacs, daffodils, black bears and mockingbirds” in “Oak Ridge, Tennessee” to “wild onion, grass, green apples” in “Lessons in Poison” to “Pears and apples, asparagus and peanuts, rows and rows of lettuce” in “Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Unlock the Secrets of America’s Secret City!”

These groupings give us as readers a view of the wildlife affected by the ORNL, but they also seem to make of the land and landscape a sort of community, a spare and haunting gathering of its inhabitants. How did you view these groupings in your poems? How do you see them in relation to the same groupings of body parts affected by the radiation, such as the “bones, fingernail, brain” you group in the first poem of the book, “Cesium Burns Blue”?

JHG: I would say it’s fair to say that as a child living in Tennessee I spent more time with the plants and animals there than I did with any fellow humans. I loved the woods and the animals we kept on our small farm and the wild things there. As a kid I pretended to be a horse and ate grass; I pretended to be a cat and climbed trees; I pretended to be a bird and built nests. There was no way those items would not become an important part of the book. I live in a beautiful part of the world now, but there’s no doubt, with every garden I plant, I’m in some way trying to recreate the beloved gardens of my childhood home.

JHG: I would say it’s fair to say that as a child living in Tennessee I spent more time with the plants and animals there than I did with any fellow humans. I loved the woods and the animals we kept on our small farm and the wild things there. As a kid I pretended to be a horse and ate grass; I pretended to be a cat and climbed trees; I pretended to be a bird and built nests. There was no way those items would not become an important part of the book. I live in a beautiful part of the world now, but there’s no doubt, with every garden I plant, I’m in some way trying to recreate the beloved gardens of my childhood home.

Also, when I studied ecotoxicology and toxic botany in college, I learned about the way that plants take up poisons from their environments, and I read studies that showed that, say, children who drank milk from cows in the Oak Ridge area or ate fish from streams even miles away were exposed to high levels of radioactive cesium, for instance, so I became aware as an adult that the fruits and flowers I loved were actually poisonous, toxic.

FTA: Are there any speculative poetry titles you’d like to recommend to the readers of the Freethinking Ahead blog? Or poetry collections that also touch on the same kind of environmental concerns that The Robot Scientist’s Daughter explores?

JHG: As far as environmental concerns, the terrific Plume by Kathleen Flenniken explores similar themes to The Robot Scientist’s Daughter from the perspective of an actual former Hanford, WA engineer who was also the daughter of a Hanford engineer. Hanford has almost more terrible lessons than Oak Ridge, from an American nuclear perspective. (Plus: google ‘the Green Run.’)

Speculative poetry that I love? Margaret Rhee’s Robot Love; Matthea Harvey’s Modern Life; Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars; Dana Levin’s Banana Palace. More female speculative poets to check out: Stephanie Wytovich, Lesley Wheeler, Nancy Hightower, Sally Rosen Kindred, Jenna Le, Shannon Connor Winward, Lana Ayers, and Mary McMyne.

[…] to T.D. Walker for interviewing me on her blog for her “speculative poets in conversation” series. I talk about my love of Tennessee, […]