The Probability Broach, chapter 2

As I’ve mentioned, The Probability Broach is a work of evangelism. Unlike Ayn Rand, whose default mode is to condemn anyone who doesn’t already agree with her, this book wants to persuade. It doesn’t assume that its audience already knows everything it has to say. It tries to introduce the author’s beliefs to readers one step at a time, and to make a case for them as it does.

However, L. Neil Smith faces a problem in doing so. Some parts of his anarcho-capitalist worldview are almost reasonable, while others are way out there. And he doesn’t know which is which.

Smith is so deep in his own ideology, he’s not cognizant of which parts of it will strike an average reader as bizarre, ridiculous, or offputting. Often, one of his wackier beliefs breaks through – surfacing from the narrative like a fly in the soup – and derails his argument. This chapter has one of those WTF-worthy moments.

To begin with, Win Bear shows off his regular-joe credentials by saying he doesn’t like most of the laws he’s supposed to enforce. He looks the other way rather than arrest people for breaking them:

“Jenny, I didn’t pass the Confiscation Act, and I feel the same about dope and tobacco: just don’t wave them around in public so I have to bust you. Hell, I even – oh, for godsake, do you have a cigarette? I’m going into convulsions!”

She shuffled through a drawer, coming up with a pack of dried-out Players, hand-imported from north-of-the-border. I lit one gratefully and settled back to let the dizziness pass. “If you repeat this, I’ll call you a liar. My hide’s been saved at least twice by civilians – people who figured we might be on the same side. Totally forgot to arrest them for weapons possession afterward. Must be getting senile.”

In this world, the U.S. has become an authoritarian socialist state, but Canada is the land of liberty. That’s a trope I haven’t seen before. (Does tobacco grow in Canada? Somehow I doubt it.)

“Vaughn’s gun didn’t do him much good, though.”

I shrugged. “Not against a machine pistol. Yes, that’s what it was. The thing about gun laws, if you’re gonna risk breaking them, it might as well be for something potent. The law only raises the ante. Look at how airport metal-detectors turned hijackers onto bombs. If it’s any consolation, it looks like your professor managed to take at least one of his attackers with him.”

There’s a germ of logic in this when it comes to zero-tolerance policies that treat all crimes as equally serious. If the punishment for every crime is the same, a criminal might as well gamble on committing a big one, if it means a bigger reward. If burglary and murder both get the death penalty, there’s no reason for a burglar not to kill the witness.

For most people, this is a reason to design laws and penalties thoughtfully. We should try to discourage people from breaking the law, but if they do break it, we should give them an incentive to come clean rather than keep racking up more crimes on their record.

But that isn’t L. Neil Smith’s take. He claims that any law against anything is useless, because laws have no effect on people’s behavior. People who weren’t inclined to commit a crime wouldn’t have done so whether there was a law against it or not, and people who want to do an illegal thing will just break the law anyway. (He says so later in the book, using almost this wording.) The idea that laws can deter crime never occurs to him.

This chapter is an expression of that viewpoint. He claims, in all seriousness, that no one would ever have taken a bomb onto an airplane if their original plan to take a gun onto an airplane wasn’t foiled by metal detectors. To put it another way: he thinks metal detectors cause bombings.

Obviously, airplane bombings aren’t an escalation of hijackings. They’re different crimes, committed for different reasons. Most airplane hijackers want to take hostages, either for ransom or to use as political bargaining chips. Airplane bombings are acts of pure terrorism, intended to inflict suffering and spread fear rather than to accomplish a concrete goal.

There are reasonable points to be made about “security theater” – measures put in place because they look good, not because they’re effective. Still, if you’ve ever flown on a plane, ask yourself: would you feel more or less safe if you knew the other passengers didn’t go through metal detectors?

Win asks Jenny Noble if Meiss had any enemies she’s aware of, but she says no. He shows her the mysterious gold coin he found at the crime scene, but she doesn’t know anything about that either. All in all, this meeting was a bust, giving him no leads to go on (but giving the author ample opportunity to lecture readers about his beliefs).

“Jenny – something else I’ll deny saying if you repeat it: Meiss knew he was going to die, but he stayed cool enough to pull the trigger four times. I disagree with nearly everything you believe, but if you’re all like that, there’ll be Propertarians in the White House someday.”

She looked at me as if for the first time, then grinned and patted me on the cheek. “We’ll make an anarchocapitalist out of you yet, Lieutenant.”

This is, of course, so L. Neil Smith can talk up how brave and manly his anarcho-libertarian freedom-lovers are. Even the skeptical cop thinks they’re badasses!

However, there are two problems with this.

First: Win says, “I disagree with nearly everything you believe,” but that’s just a lie. When he gets transported to anarchocapitalist utopia in a few chapters, he fits in immediately.

Indeed, his dialogue in this chapter shows that he was already sympathetic to their ideology. Despite being a police officer, he doesn’t dislike or distrust them, and he just said that he doesn’t enforce laws he doesn’t agree with if he has an excuse not to. This isn’t genuine disagreement; it’s the Lee Strobel trick of pretending to be a skeptic so your “conversion” seems more convincing to naive readers.

Second: Win’s praise falls a little flat when you consider that Meiss was killed in a drive-by shooting. That’s not the kind of death that affords ample time for reflection.

He was able to shoot back, but that’s not proof that he “knew he was going to die, but he stayed cool”. He might just as well have reacted on instinct, firing in blind panic before he knew what hit him.

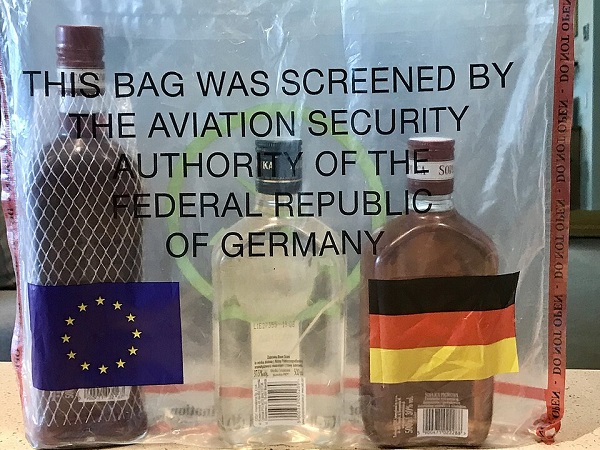

Image credit: Kgbo via Wikimedia Commons; released under CC BY-SA 4.0 license

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series:

Smith really thinks that if a would-be terrorist can’t bring a gun onto the plane (to threaten the pilot with, I guess?) that he’d instead bring a bomb, which, if detonated, would kill everyone on board including the hijacker himself? Did he still believe that after 9/11 where the terrorists used boxcutters instead? His “reasoning” makes no sense.

Tobacco actually does grow in Canada. Canadian folk singer Stompin’ Tom Connors even wrote a song about tobacco farming (and what horrible, back-breaking work it is), called ‘Tillsonburg’, after the town in Ontario that had tobacco as one of its major industries. (And he knew what he was talking about, as he’d actually worked there doing that for a time.)

I guess it didn’t occur to L. Neil Smith that pulling the trigger on a gun repeatedly and quickly could equally – maybe more so even – be evidence that the shooter was NOT cool rather than that they were. Reacting by firing a gun again and again could well be taken as panicking and shooting needlessly rather than pausing to respond in a more sensible and considered way. Trigger happy does NOT equal cool or good.

Private property was originally a workaround for scarcity by creating the idea that one person had a greater claim than another to some limited resource through a stronger association with it.

But if we lived in the kind of abundance-based economy the Industrial Revolution was meant to deliver before it was sabotaged by manufactured scarcity, and there was enough of everything to go around everyone and some to spare, what would “That one’s mine” even mean?

I have two thoughts in response to your comment,

First, while scarcity can be reduced, i.e. our productivity could currently feed, clothe, shelter, provide medical care, education, communication tools, and transportation to everyone on the planet, there will still be scarcity of some sort. For example, the desire to eat at a specific restaurant at a specific time creates a limitation in the number of people who could do so, and thus there scarcity is created. Which then creates value. The desire to reside in a certain location, say Hawaii, is limited by the physical amount of land. I’m not saying that we couldn’t do a lot better, or that your point about manufactured scarcity is invalid, but there are conditions which will always generate scarcity and lead to the creation of the concept of value. This is part of life, and even if we reduce scarcity as much as we possibly can, life will continue to consist of compromises between things we value. Even the wealthiest and most powerful people on earth are forced to compromise their desires, although a number of these people apparently never learn that compromise is an inevitable part of life.

Second, I also think that there is an innate psychological part of ourselves which understands and wants to experience ownership. What I mean is that the statement of “that one’s mine” is an idea/feeling which will not go away with the elimination of scarcity. Even today if I held a party where everyone received identical pencils in order to play a game, there would be people who, once they were given the pencil, would consider it theirs for at least as long as the party lasts. They would feel resentment if someone took it from them, or if they were forced to use the pencil which was given to someone else. The concept of ownership is, I believe, buried deep within our primate brain. And it may even be quite older. Dogs with their toys appear to feel ownership and will refuse to play with an identical ball if it is not the one they think is right, and they will get into fights if another dog takes something they feel they own. This doesn’t mean that people (and dogs) can’t and won’t share, but they like it to be their choice and not forced on them.

I’m not saying you are wrong, only that the idea that without scarcity the phrase “That one’s mine” would be meaningless does not match my understanding of how humans behave.