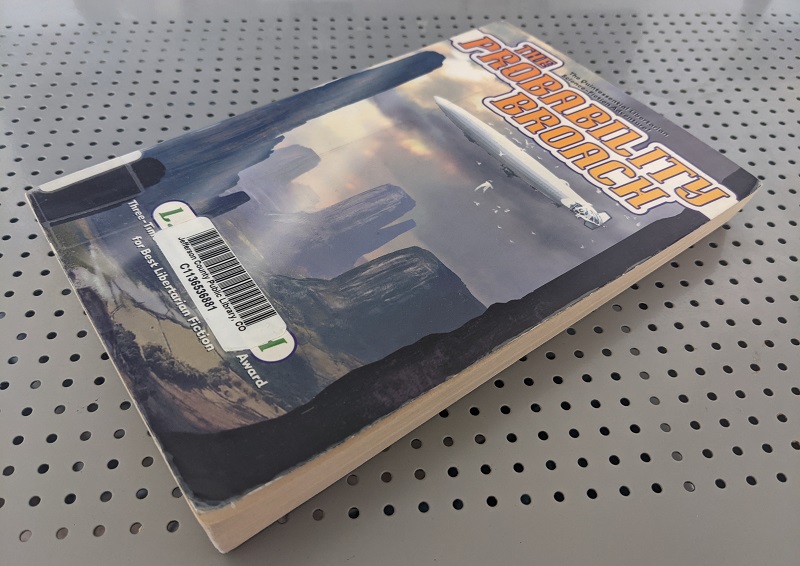

The Probability Broach, chapter 1

Lieutenant Edward “Win” Bear sits in his car, contemplating his life choices:

Twenty-seven years on the force, and now the pain was creeping down my left arm into the wrist. Maybe it was the crummy hours, the awful food. Maybe it was worrying all the time: cancer; minipox; encountering an old friend in a packet of blackmarket lunch meat…

Forty-eight was the right age to worry, though, especially for a cop. Oh, I’d tried keeping in shape: diets, exercise, vitamins before they got too risky. But after Evelyn had split, it just seemed like a lot of trouble.

Ayn Rand uses this same dishonest tactic: describing evils that exist because of unregulated capitalism, and blaming them on socialism. This is a case in point.

Smith expects us to believe that government regulation – not greed or the hunger for profit, not sloppiness or corner-cutting, not callous disregard for customers’ health, not relentless competitive pressure in a Prisoner’s Dilemma market – is what compels businesses to sell tainted vitamins and adulterated food.

This assertion runs smack into a wall of reality. When these kinds of scandals happened for real, it was because businesses were unregulated – not because regulation somehow forced them to do it. I’ll quote the famous passages from Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle about the American meatpacking industry:

There was never the least attention paid to what was cut up for sausage; there would come all the way back from Europe old sausage that had been rejected, and that was moldy and white — it would be dosed with borax and glycerine, and dumped into the hoppers, and made over again for home consumption. There would be meat that had tumbled out on the floor, in the dirt and sawdust, where the workers had tramped and spit uncounted billions of consumption germs. There would be meat stored in great piles in rooms; and the water from leaky roofs would drip over it, and thousands of rats would race about on it. It was too dark in these storage places to see well, but a man could run his hand over these piles of meat and sweep off handfuls of the dried dung of rats. These rats were nuisances, and the packers would put poisoned bread out for them; they would die, and then rats, bread, and meat would go into the hoppers together. This is no fairy story and no joke; the meat would be shoveled into carts, and the man who did the shoveling would not trouble to lift out a rat even when he saw one — there were things that went into the sausage in comparison with which a poisoned rat was a tidbit.

…and as for the other men, who worked in tank rooms full of steam, and in some of which there were open vats near the level of the floor, their peculiar trouble was that they fell into the vats; and when they were fished out, there was never enough of them left to be worth exhibiting,—sometimes they would be overlooked for days, till all but the bones of them had gone out to the world as Durham’s Pure Leaf Lard!

This stomach-churning description has a recent parallel, the 2024 listeria outbreak at a Boar’s Head meat-processing plant. When food safety inspectors checked the plant, they found mold, vermin and filth:

Between Aug. 1, 2023, and Aug. 2, 2024, inspectors found “heavy discolored meat buildup” and “meat overspray on walls and large pieces of meat on the floor.” They also documented flies “going in and out” of pickle vats and “black patches of mold” on a ceiling. One inspector detailed blood puddled on the floor and “a rancid smell in the cooler.” Plant staff were repeatedly notified that they had failed to meet requirements, the documents showed.

Needless to say, in an anarcho-libertarian world like the one Smith envisions, problems like this would be impossible to detect or do anything about. With no regulatory watchdog, there’d be no way to track outbreaks of foodborne disease. There would be nowhere to report them to, and no one whose job it was to connect the dots and figure out what all the sickened people were eating.

Even if you assume private parties would arise to perform this function, there’s another problem. In a world of absolute property rights, there would be no universal rule about what level of cleanliness was required. No business would be compelled to let anyone in to check if sanitation standards were being upheld. Nor would there be anyone with the authority to order a recall. True, a business might do it voluntarily to protect their reputation, but they’d have just as strong an incentive to deny or minimize the problem.

Lt. Bear continues his ruminations:

Maybe it was a depression they wouldn’t call by its right name, or seeing old folks begging in the streets. Maybe I just watched too many doctor shows.

Again, bear in mind that this is supposed to be a socialist dystopia, where the government exercises power over the economy. So why are there are so many homeless elderly begging on street corners? Are there no social safety nets, no public housing, no fiscal stimulus programs? Smith makes it sound like people are completely on their own, which is supposed to be what happens in major depressions in capitalist economies.

It would be one thing if Smith tried to make a case for how this all came about. But he doesn’t. Other than these brief asides, the book contains very little description and no backstory for Win Bear’s world.

For libertarians, it’s an article of faith that the government is the cause of every evil. They don’t view it as a policy position to be justified through argument, but a dogma, not to be doubted or questioned. They take this so thoroughly for granted, they tend to forget that not everyone else believes it.

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series: