At the beginning of 2020, I received a one-year subscription to Scientific American. I embarked on a blogging series in which I read articles about physics, and offer my commentary as a person with a PhD in physics. I may continue this series in 2021, but instead of reading articles in Scientific American, I’ll take reader requests. Just send me any articles or videos that you’d like me to discuss or explain. Requests must obey the following restrictions:

- It must be intended for popular audiences, as opposed to scholarly audiences.

- It must be about physics or adjacent to physics. I will also consider requests for math-related articles.

- I must have access to the article or video. Note, I still have a Scientific American subscription, so those are fair game.

New or old articles are welcome, and videos too. I will exercise my own discretion among qualifying requests, taking into consideration how much time it would take me to process, and how interesting I think it would be to write about. To make a request, leave a comment or e-mail me at [email protected].

Below the fold, I have my review of the articles I’ve written about so far.

- The triple slit experiment

- Giant Atoms

- The Cosmic Crisis

- The milky way

- Quantum Steampunk

- A planet is born

- The darkest particles

- Quantum Leap

- Interstellar Interlopers

- Orbital Aggression

- Explosions at the Edge

Of these eleven articles, four of them were about astronomy (4, 6, 9, 11). Three more were arguably also about astronomy–“Orbital aggression” being about space policy, “The Cosmic Crisis” being about cosmology, and “Giant Atoms” being about a device that will be used to do astronomy. One was about high energy physics (7), two were about condensed matter (5 and 8), and one was basic quantum physics (1).

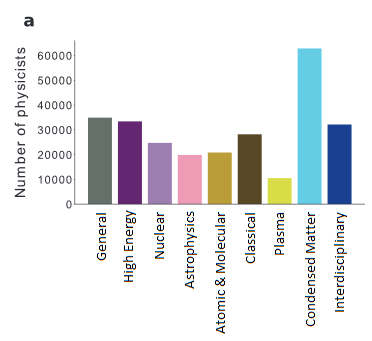

This is not at all a representative sample of physics research. Based on a census of physicists, here’s what the numbers really look like:

Fig 1a from Battiston et al., modified to expand out abbreviations

There are three articles that I remember as being bad. “Quantum Leap” was easily the worst, being totally incomprehensible in its explanations of the science, and painfully self-aggrandizing. “Quantum Steampunk” was more tolerable in character, but also failed to explain most of what it set out to explain. I also consider “The Triple Slit Experiment” to be one of the worst, because it misled readers into thinking it was about an exciting quantum effect, when in fact it was a much less exciting classical effect.

I observe that the three worst articles were exactly those which were in or adjacent to condensed matter physics. Hey, that’s my field! And frankly, that has been my experience among scholarly articles as well. Condensed matter physics papers are just really hard to understand. It’s a combination of condensed matter physicists being poor communicators, and the underlying ideas being inherently difficult to communicate. If physicists can barely communicate their ideas to each other, what hope is there of communicating to popular audiences? And because scientists so rarely attempt to communicate condensed matter physics to popular audiences, scientists rarely build up the skills and narratives needed to communicate, and the general population rarely builds up the background needed to understand. It’s a vicious cycle. No wonder condensed matter is underrepresented in popular physics, while astronomy is overrepresented.

When I started this series, I had a loose idea of several topics I would touch upon throughout the year. For example, I would talk about how scientists often put the emphasis on what new things they learned (which are often more controversial than the scientists make it out to be), when what readers really need is an explanation of established theory. I also wanted to discuss the many colorful metaphors and analogies that float around in popular science. These metaphors can be helpful to popular audiences, but are often confusing to me, as I struggle to connect to my own foundation of understanding. Another point I wanted to make, is that my standards for understanding are very different from that of non-experts. I feel I understand something if, with some effort, I could write out equations and make inferences on my own. Non-experts usually have a lower standard, so a metaphor that makes sense to a non-expert may not make any sense to me, even if I have extracted more information from the metaphor than the non-expert did.

I didn’t get to most of these points in the series (although I did touch upon the first point in “Explosions at the Edge“). And that’s because Scientific American overall surpassed my expectations. Case in point, although “The Triple Slit Experiment” is on my worst list, I went easy on it because it was the first article I wrote, and my expectations were lower at the time.

I think Scientific American sets a higher standard, because its articles are generally written directly by scientists, or by science journalists who are particularly attentive to scientists. And even when Scientific American fails, its failures generally arise from the biases of scientists. That is, scientists are not always good at communicating, and have a tendency to oversell their own particular contribution.

And that’s one of the reasons why I’m opening up this series to requests. By including a broader range of sources, we’ll get to examine a broader range of issues with popular physics.

I appreciate your perspective and intention on sharing your knowledge. I’m reading “Knocking on Heaven’s Door” right now by Lisa Randall. Do you have a take on that? (Yes, I know the “rules” of grammar regarding titles of poems or books or whatever, but this venue doesn’t allow for some of those conventions to be followed).

I know it’s obnoxious to have to make remarks to keep the pedants from being snarky, but I feel the need. (And PLEASE delete this as a “non-post,” and you even have my permission to delete the parenthetical remark I previously made–if you wish).

@ANB,

I won’t take books as requests.

I did read a Lisa Randall book once. It was a long time ago, but I don’t recall being very impressed by the writing.