Liberationism vs assimilationism is a historically important dichotomy, which dates back to the gay liberation movement of the 1960s. It put a name to certain political disagreements among LGBT/queer people that persist to the present day. That said, in the present day, liberationism/assimilationism is less relevant, just one lens of many that we may apply whenever it seems particularly apt (e.g.). And often, when we do talk about the dichotomy, we feel the need to re-explain what the dichotomy even is.

Ahem… In a contemporary context, assimiliationism refers to the desire to blend in with mainstream culture, to emphasize “we’re the same”; while liberationism refers to a desire for more radical change. A somewhat longer explanation is available here.

A recent video by Rowan Ellis revives the liberation/assimilation dichotomy for the purpose of understanding different forms of queer representation. I hate it, and it illustrates how the liberation/assimilation lens can go so wrong.

The primary problem, is that “liberation vs assimilation” has largely been collapsed into “good vs bad”, while explicitly denying it. Rowan Ellis says,

It’s not necessarily that assimilation films are bad and liberation films are good. […] In the way in which it deals with LGBT stories and identities, for me, the liberation stuff comes up top. (14:23)

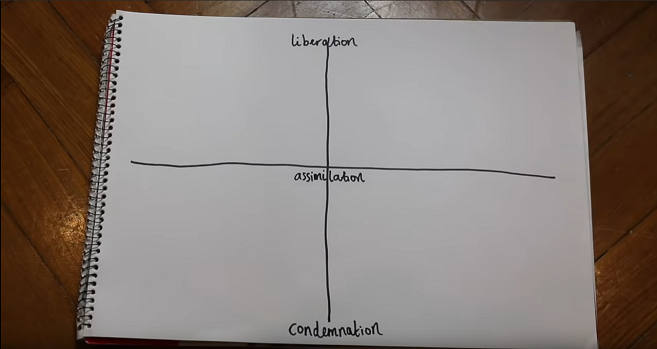

She frames it as a neutral dichotomy, in which she has an expressed personal preference. But the way the dichotomy is framed is far from neutral. Indeed, within seconds, she draws a spectrum that goes from condemnation to liberation, with assimilation placed at the halfway point.

In the video, Rowan Ellis provides multiple comparisons of movies/shows that she considers liberationist or assimilationist, and in each case she argues that the liberationist representation is better. In a later video, she argues that the problem with Love, Simon is that it’s assimilationist. I don’t wish to defend or criticize any of these particular examples, but her choice of examples clearly establishes a framework in which liberationist media is just better. And I wish she would own up to it instead of pretending to be neutral.

It might be said that the liberationist/assimilationist dichotomy cannot be neutral. After all, the dichotomy was created by the gay liberation movement to describe the differences between their own views and those of their political opponents. Those who were called assimilationists likely did not call themselves assimilationists. I mean, it’s kind of an inherently negative word, a sure sign that assimilationists had little say in the creation of this whole narrative.

And that’s okay. We uphold our own views as enlightened, call our opponents nasty names, that’s politics. But it’s a poor fit for trying to describe different forms of queer representation, because it implies a strong judgment on people who don’t prefer the “right” kind.

When Rowan discusses the reasons why people might like assimilationist representation, she says that sometimes liberationist media is just made poorly, or it’s less accessible. She discusses how mainstream representation is important to change mainstream attitudes towards queer people. However, she seemingly can’t imagine any reason why queer people might enjoy assimilationist media for itself. She practically conflates “assimilationist” with the idea of being targeted at mainstream audiences, rather than queer audiences.

So here’s my personal experience. I watch lots of indie films, mostly focused on gay/bi men, mostly drama or romance. They’re mostly not very good, and I wouldn’t say I enjoy them so much as I enjoy complaining about them. (No specific examples, because my memory isn’t so great, and I’m not willing to do the research.)

I don’t know which of these might be considered assimilationist or liberationist, because that’s not a lens I use. However, I observe that some of them try to portray gay men’s lives in all their super gay glory, and it just falls so flat. Often, it’s based on the writer/director’s personal experiences with the gay social scene, and on the assumption that their experiences are representative. Depicting how queer lives can be different from straight lives: A-OK. The oppressive assumption that most queer people lead more or less the same different life: not okay. This is something I feel keenly, being a queer ace SJW in STEM with low emotional expression. Sometimes what queer creators consider liberation doesn’t have any more room for me than assimilation does.

And this is the problem I have with the assimilation/liberation lens. It puts all the focus on whether the queer lives portrayed are similar or different from those of straight people. What about the differences between queer people? If we are all different, then it stands to reason that some queer people like “assimilationist” media, not because it’s mainstream, but simply because it more accurately reflects their lives. Some might prefer “liberationist” media because that more accurately reflects their lives. And some of us… are just perpetually disatisfied with all media.

Self-identities are a fun topic. I recently wrote about this here — https://andreasavester.com/why-humanity-should-stop-enforcing-mandatory-self-identities/

For me personally my sexual orientation isn’t a core part of my self-identity. I qualify as bisexual? So what? That’s just a fact about me, that’s not a significant part of my identity just like “grey-eyed” isn’t an important part of my identity either. Or my gender dysphoria. I prefer to live as a man even though anatomically I happen to be female. Why should I therefore have some kind of special “trans identity”? I’m just a person who prefers male fashion and uses male pronouns. That’s all.

I don’t really see other LGBTQIA+ people as “my in-group.” Sure, I have friends who are also LGBTQIA+. I can hang out with the community. I have advocated LGBTQIA+ rights. I share the same goals with the community. But that’s all. I won’t say that LGBTQIA+ people are “my people” as opposed to the rest of the world who are “other” and “different.”

I’m not trying to fit in. I’m not apologizing for my differences. Yes, I’m here, and transphobes might as well get used to it. I believe that the society should accept me, and I simply cannot change myself to mold into hetero-normative society. Yet I consider myself “human.” That’s my identity. I am a normal person who lives a mostly ordinary life. I want equal rights and recognition. (But no house with a white picket fence and 2.5 kids, individual houses create unnecessarily large carbon footprints, and I prefer to remain childfree.) Anyway, the point is that I don’t really have a queer identity, I consider myself human, and I strongly dislike having some minority identities forced upon me against my will.

Siggy, I think one key point you make here is that some people assume that certain films are “representative”. Maybe this is an issue?

Imagine two films being made of a straight male and female couple. Perhaps one couple are straight pron-film actors, while the other film’s couple has a preacher, his wife, and their six kids. Both films show different ways of being straight couples. But nobody thinks either film is “representative” of THE way that all straight couples live. Clearly not.

My point is simply that if more LGBT films were made and marketed and watched by everyone, then people would be less likely to take some films as being representative of everyone in a group. Conversely, if most people only saw one or two films or TV shows per year with a straight couple, many strange ideas might be hypothesized.

So while I know nothing of the major axis of your posting here, I just note that it’s effect may be magnified by this somewhat unrelated issue.

But whether LGBT or straight etc, stories chosen for moviemaking are only representative of anything as an incidental component. Movie producers want something unusual to make their movie sell. And to a 90+% straight audience, a movie with an LGBT couple is a movie that “represents” LGBT culture, even if everyone who made the show was a Shakespeare, trying to explore serious dramatic themes. It’s hard for audiences to overcome their initial preconceptions.

It strikes me that one of the problems with such a simplistic dichotomy is that it does not take account of the kind of society that LGBT+ people might be trying to assimilate further into or liberate themselves further from.

In particular, a very individualistic, progressive society which respects diversity and accepts different modes of being is one to which assimilation is a kind of liberation. Being part of that society on the same footing as everyone else is being able to express one’s uniqueness and individuality, and being respected for it. It is not the sort of society one can really liberate oneself from either, as deciding to settle down into a very traditional mode of being is itself an accepted variation on the human condition. Furthermore, even if a society is not particularly individualistic, tolerant and progressive, by assimilating into it with a different form of experience one is actually taking it further in the direction of individualism, progress and tolerance. The act of assimilation can itself be a step on the way to liberation.

In short, this lens mistakes directionality for values. Simply being mainstream or countercultural is not a value, it is a proximity to a value, and unless that value is spelled out, the directionality is meaningless.

I’ve heard arguments of this kind made in several LGBT+ contexts. Most recently it was about drug-taking and risky sex parties among gay men. Some argued in favour of it because it was “part of our culture”, and condemned those who said the practice should be discouraged as heteronormative and assimilationist. What they failed to appreciate was that, part of the culture it might have been, but it is also risky, dangerous and often a cause of harm. The question is not whether it is a part of the culture, but whether it ought to be on health grounds. How transgressively counter-cultural it is doesn’t really matter, how damaging it is rather does. On the flip side, one might point to racism as a very traditional and mainstream cultural form, but the issue is not how mainstream it is but how morally repugnant it is. LGBT+ people should not reject racism because it’s mainstream and common among straight, cis people, but because it’s a bad thing in itself.

@cartomancer #3,

Julia Serano has called this “subversivism“, which is a term I think should get more use. I should probably take the opportunity to blog about it.

cartomancer @#3

There’s one more problem here. It’s harmful for people to imagine that there can be a right or a wrong way how to be gay or queer or trans or whatever. For example, there exist gay men who are risk-averse, do not like using drugs, and prefer monogamous relationships. A culture, which prescribes a set of behaviors that appeal to only some members of the community, is problematic.