This is a small programming project I worked on in 2013-2014. Although I wrote a blog series about it at the time, this is not a repost of that series. Instead, this is a repost of the explanation I wrote earlier this year, when I uploaded the project to github. If you liked this article, you might also enjoy this interactive game, although I had nothing to do with that one.

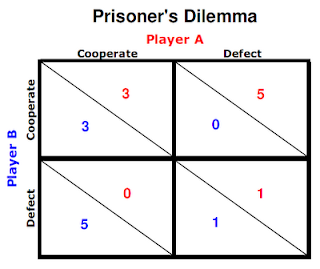

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is an important concept in game theory, which captures the problem of altruism. Each of the two players chooses to either cooperate or defect. Cooperating incurs a personal cost, but benefits the other player. If both players cooperate, then they are better off than if they had both defected. In a single Prisoner’s Dilemma, it seems that it’s best to defect. However, if there are multiple games played in succession, it’s possible for players to punish defectors in subsequent games. When multiple games are played in succession, it is called the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma (IPD).

The best approach to the IPD is highly nontrivial. In 2012, William Press and Freeman Dyson proved that there is a class of “zero-determinant” strategies that seem dominant, and which would lead to mostly defection. However, Christoph Adami and Arend Hintze showed that the zero-determinant strategies are not dominant in the context of evolution. Understanding this issue could elucidate why humans and other creatures appear to be altruistic.

How the simulation works

- We have a population of 40 individuals. Each individual has 4 parameters that govern how they play IPD.

- Each individual plays IPD against 2 other individuals in the population, and their fitness is calculated from their average score.

- One individual dies, and another reproduces. The probability of reproduction increases with fitness, and the probability of death decreases with fitness.

- All the parameters of the individuals are mutated by small amounts.

- Steps 2-4 are repeated a million times. Each repetition is called a “generation”.

How the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma Works

The Prisoner’s Dilemma has the following payoff matrix:

Image credit: Blank On The Map

A simple strategy is to have a certain flat probability of cooperating. However, in the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma, this probability could depend on the results of all the earlier games. The simplest case is when the probability depends only on the result of the previous game. Since there are 4 possible results of each game, that means we need 4 probabilities, each between 0 and 1. Thus, each individual has 4 parameters:

- Parameter 1 is the probability of cooperating if the last game was CC (all cooperated)

- Parameter 2 is the probability if the last game was CD (I cooperated, other player defected).

- Parameter 3 is the probability if the last game was DC (I defected, other player cooperated).

- Parameter 4 is the probability if the last game was DD (all defected).

The other question is, how many iterations do we play? In fact, it is possible to calculate the average outcome over an infinite number of iterations, using Markov chains. The method is described by Press & Dyson, and it is what I use in this simulation. The catch is that none of the parameters can be exactly 0 or exactly 1, lest the method fail.

Results

The evolutionary trajectory of the population is shown in the video below:

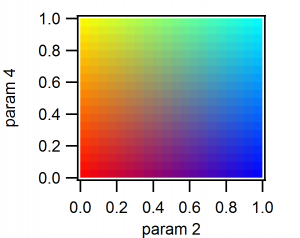

Each individual is represented by a colored pixel. The location of the pixel represents the value of parameters 1 and 3. Some pixels may represent multiple individuals at the same location. The color of the pixel represents parameters 2 and 4, according to the color scale below:

(Apologies that I did not come up with a more color-blind-friendly graphical representation.)

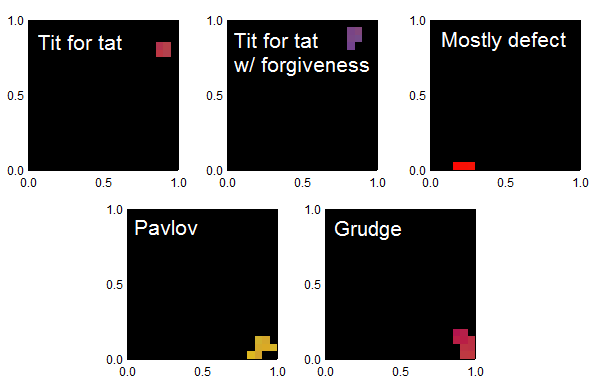

As we can see from the movie, the population is highly unstable, and continues to change even after a million generations. Below I identify several strategies that are similar to ones with common names. There are also many strategies in the video that don’t have any names that I know of.

Other games

I was worried that the simulation might be unstable simply because the mutation rate is set too high. So I tried the simulation again, adjusting the payoff matrices so that it would use a different game.

First we have Battle of the Sexes. In Battle of the sexes, a married couple is deciding what to do for the night. One prefers to go to the football game, but his husband prefers to go to the opera. However, whatever they choose to do, they both strongly prefer to stay together. In this game, “cooperation” is going with the other player’s preference, and “defection” is going with one’s own preference.

Here are videos of two simulations of the Iterated Battle of the Sexes:

Each simulation appears to settle on a relatively stable equilibrium, but interestingly different simulations show different equilibria. The first simulation shows a population that likes to take turns, while the second simulation shows a population that likes to hold on to dominance as long as possible.

Second we have Stag Hunt. Two individuals go on a hunt. Each can choose to go after a stag (cooperate) or after a hare (defect). Going after the stag offers the biggest payoff, but only if both players choose to hunt the stag. If only one player hunts a stag, then they fail to catch anything, while the other player catches a hare.

Here is the evolutionary trajectory of a population that plays Iterated Stag Hunt:

It seems that the population settles on hare hunting. However, on repeated simulations, sometimes they settle on stag hunting.

Conclusion

The Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma appears to lead to an evolutionary trajectory marked by instability. This instability is particular to the Prisoner’s Dilemma; similar simulations of Stag Hunt and Battle of the Sexes lead to more stable populations.

Of course, it’s plausible that with different simulation settings and procedures, the population could eventually settle in a stable state. This has been shown in some of the literature. Creating this simulation gave me an appreciation for how difficult this problem is, and why it is the subject of an entire field of research.

How about a link to the source on GitHub?

@Curt Sampson,

No link, because I’m partially pseudonymous. (Yeah yeah, I linked to my Youtube channel, whatever.) I won’t stop you from finding the code with Google, but I should warn you that it’s coded in Igor Pro.

“Partially Pseudonymous” would be a good name for a band. That is all.