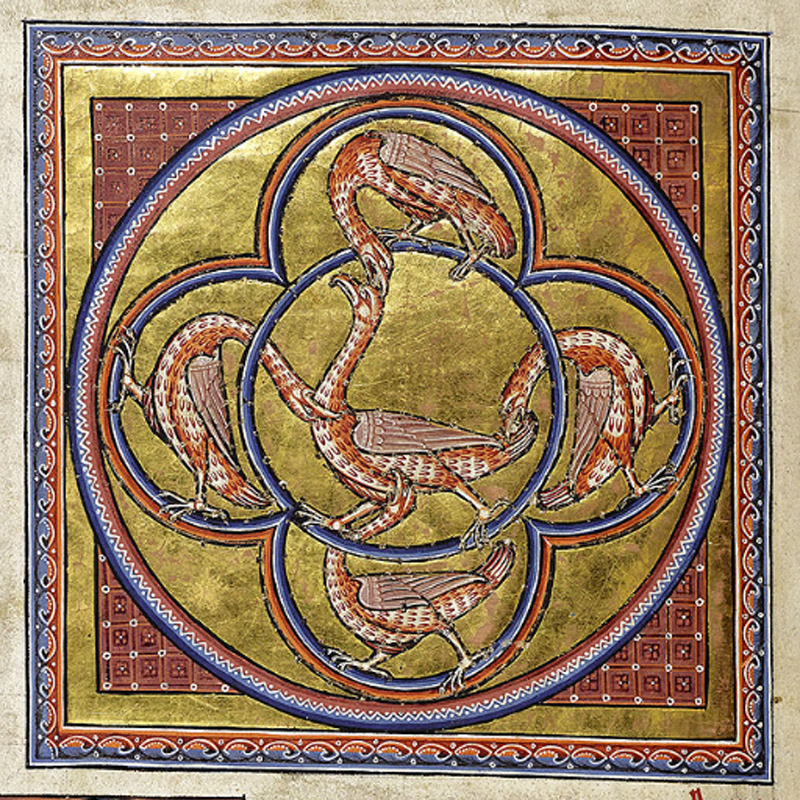

Two fierce birds oppose each other in a circle. The Bestiary illustrators did not know vultures, so the bird tends to look similar to the eagle.

Text Translation:

Of vultures. The vulture, it is thought, gets its name because it flies slowly. The fact is, it cannot fly swiftly because of the large size of its body. Vultures, like eagles, perceive corpses even beyond the sea. Indeed, flying at a great height, they see from on high many things which are hidden by the shadows of the mountains. It is said that vultures do not indulge in copulation and and are not united with the other sex in the conjugal act of marriage; that the females conceive without the male seed and give birth without union with the male; and that their offspring live to a great age, so that the course of their life extends to one hundred years, and that an early death does not readily overtake them.