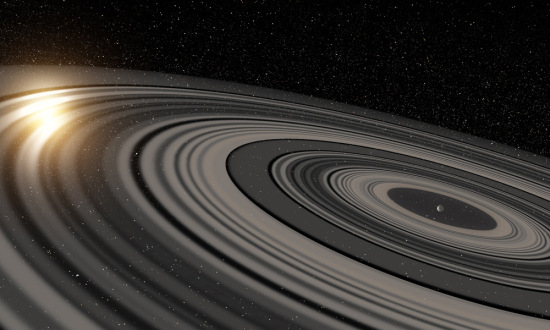

Artist’s conception of the extrasolar ring system circling the young giant planet or brown dwarf J1407b. The rings are shown eclipsing the young sun-like star J1407, as they would have appeared in early 2007. Credit: Ron Miller

There are many beautiful sights to be seen in our solar system and more coming into view everyday. But when it comes to superstars, every child knows the answer: Saturn! It is hands down our most famous planetary celebrity and for good reason. Easily seen in a small telescope, the disk hangs in space like a gilded jewel cradled by spectacular rings of gold. With greater resolution the rings only improve, taking on features of a finely machined phonograph, first hundreds and then thousands of individual strands appear, each carefully etched into space over eons by Newton’s best legal work, some twisted by tiny, growing shepard moons into intricate braids of yellow and orange. You could spend a lifetime exploring the intricacies of those rings, and some scientists do!

Whereas Jupiter turned into a mini-solar system, well ordered with four large moons standing in for diminutive planets, Saturn seems to have taken the demolition derby approach, full of wreckage left by colliding moonlets. The rings are thought to be one result of those ancient catastrophes large and small, perhaps maintained by periodic cryo-volcanoes emitted by nearby icy moons flexing in Saturn’s relentless tidal grip. Other astronomers believe they may be, in their current incarnation, a relatively temporary structure. If so we’re lucky their cosmic life overlapped our own.

The other gas giants have rings of a sort, mostly dim and hard to see, some merely dusty arcs that don’t even make a full circle, nothing to compare with Saturn. But some astronmers have found another ringed gem hidden in exo-planetary data. Careful analysis of eclipsing starlight shows it also has rings, and they are huge:

From Quarks to Quasars — Astronomers at the Leiden Observatory, The Netherlands, and the University of Rochester, USA, have discovered that the ring system that they see eclipse the very young Sun-like star J1407 is of enormous proportions, much larger and heavier than the ring system of Saturn. The ring system — the first of its kind to be found outside our solar system — was discovered in 2012 by a team led by Rochester’s Eric Mamajek.

A new analysis of the data, led by Leiden’s Matthew Kenworthy, shows that the ring system consists of over 30 rings, each of them tens of millions of kilometers in diameter. Furthermore, they found gaps in the rings, which indicate that satellites (“exomoons”) may have formed. The result has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal.

“The details that we see in the light curve are incredible. The eclipse lasted for several weeks, but you see rapid changes on time scales of tens of minutes as a result of fine structures in the rings,” says Kenworthy. “The star is much too far away to observe the rings directly, but we could make a detailed model based on the rapid brightness variations in the starlight passing through the ring system. If we could replace Saturn’s rings with the rings around J1407b, they would be easily visible at night and be many times larger than the full Moon.”

One of the reasons Saturn’s rings are so gorgeous is because they dwell in a region well past the frost line, where substances like water form shiny grains of ice, and they hug a planet with a bottomless atmosphere that strongly favors yellow wavelengths, lending the rings an exquisite golden hue so bright they almost appear lit up from the inside out. In the case of the proposed new exo-planet, astronomers can’t really say much about color or reflectivity. But the system is young, it’s probably still violent, lots of collision and mergers going on, at least one big gap is suspected where a large moon may be sweeping up material. This young planet is many times the mass of Jupiter, it’s probably still growing and glowing, maybe its a a sullen red spark of an eye glaring out of the ring system at the lower edge of our visual acuity in visible light, maybe more rose-colored, or it could still be hot enough with the heat of formation to shine a golden yellow brighter than Saturn.

These rings are so big they would stretch from the Earth to the sun, the star J1407 is similar to our own, and the planet is far enough away that it may take about ten years to make a single orbit. So, much like Saturn, they could well be spectacular if seen in visible light. Maybe they would look something like this if the new planet was in the same place in our solar system that Saturn currently occupies.

Wow. Now I really can’t wait for the James Webb to be built, and I hope it’s turned towards this system, at least briefly. That sounds amazing. I’ve always loved the rings. It’s why Saturn is my favorite planet (not Pluto). This planet highlighted sounds like an absolute sight to behold. Maybe, one days, humans will get to behold it.

Wait. This is awesome, but I’m confused.

Rings form when an orbiting object is close enough – inside what’s called the Roche limit – that the difference in gravity between the near side and the far side tears the thing apart. How close is “close enough” depends on the mass of whatever the rings are forming around. From your description, this “planet” is big enough that you almost have to call it a star, so its Roche limit would be further out than Saturn’s or Jupiter’s. But if the ring system covers ‘the distance from the Earth to the Sun’, then its Roche limit would have to be at least half an AU out. Mercury is closer to the Sun than that, so the Sun’s Roche limit must be smaller. Which would mean this exoplanet would be more massive than the sun… so why hasn’t it ignited into a star?

Are these rings from a different cause? This is apparently a young system – rather than debris from former moons that were broken up, or were too disrupted to ever form, are these rings made of matter that hasn’t had a chance to collect into moons yet? Are these temporary rings, eventually to be replaced by a spectacular moon system?

Those are really good questions, Robert. And I wish I knew the answers. Since there is disagreement over how Saturn’s rings formed and how long they’ve been around in their current glorious state, it’s hard to even guess at some of the answers. But we have good examples of rings around stars, see Beta Pictoris; this ringed planet is huge, it’s borderline brown dwarf big, the system is very young, so it’s entirely possible these rings represent an early snapshot in time more consistent with how solar systems and planets and moons form than the debris of a sizable object that wandered inside Roche’s limit. But with all the stuff that’s probably happening in the nebula around a young system, that could be exactly what happened.

We don’t know why Jupiter went the organized route and Saturn didn’t. But one big factor could have been Saturn’s location, current theories strongly suggest it started out as the outer most major planet (Unless there was another one further out that spiraled in or got kicked out completely out). Uranus and Neptune probably formed inside Saturn’s orbit. Early on, about 4.2 billion years ago, Saturn and Jupiter got into a 2:1 resonance, where Saturn completed one orbit for every two orbits by Jupiter. Which means they would have lined up in the same place in the solar system every thirty years or so. It is believed that this is what shot Uranus and Neptune out of their closer orbits, which means both would have crossed Saturn’s orbit or come close given it happens in three-d, and either one could have put some real hurt on whatever was forming around Saturn at the time if they came close enough.

And once Neptune and Uranus were way out, they would have slung existing planetoids like Pluto’s and Quauars all over the place, and some of those those could have wondered close to Saturn and wreaked havoc on whatever was trying to form there.

Will they be swept up into a moon/planet or remain as rings? Again, both entirely possible, for those parts of the rings close enough in anyway, because we have examples of both happening right in our solar system. Jupiter standing in for a traditional, organized planetary system analogue, and Saturn representing the demolition derby version where only one large moon formed and went on survive into present day surrounded by wreckage and rings.

Huh. Now I wish I’d studied more astronomy in school, this stuff is awesome. I hadn’t thought that something besides tidal forces could rip something apart and form rings. And any mention of orbital resonance gives me warm fuzzy feelings.

Good illustration and fascinating system here. Mind you given its a star not a planet with X times the mass of Saturn (95 earth masses if you’re wondering for the butterscotch giant) you’d certainly expect this star to have a big more heft in its rings.

BTW. Love the second illustration with the cathedral (?) and blue sky – but I don’t think I’m the only one seeing that and thinking it looks like a ‘Mortal Kombat’ style portal or a Buffy-verse hellmouth am I?

The eye of God, perhaps?

Hi, this is the authour of the paper here – a friend pointed me to the blog!

To answer your questions:

Robert B. – you are right, these rings are over a hundred times larger than any Roche limit, and so these rings are ultimately unstable. They’ll accrete into moons and eventually disappear – we’re seeing this system in a very young system though (only 16 million years old) so we think they haven’t had a chance to do that yet.

Stephen – just to be clearn, with the beta pictoris system, there is a wide ring around the star, not the planet. The planet beta pictoris b is orbiting the star in a cleared region within this circumstellar disk.

What *is* exciting is that I think there may be rings around the beta pictoris b planet itself! In 1980, a french astronomer saw the light from beta pictoris fluctuate over a one month period – a hint of the shadows of rings about another young planet? Time will tell.

Many thanks for all your interest in this system. We didn’t expect quite this reaction!

Best,

Matt