To look for life

is to find death.

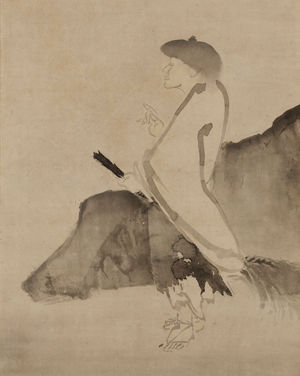

Honami Koetsu “riding the ox”

The thirteen organs of our living

are the thirteen organs of our dying.

Why are the organs of our life

where death enters us?

Because we hold too hard to living.

So I’ve heard

if you live in the right way,

when you cross country

you needn’t fear to meet a mad bull or a tiger;

when you’re in a battle

you needn’t fear the weapons.

The bull would find nowhere to jab its horns,

the tiger nowhere to stick its claws,

the sword nowhere for its point to go.

Why? Because there is nowhere in you

for death to enter.

Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s Hakagure contains the famous expression you may have heard, “The way of the samurai is death.” It is usually quoted in a vacuum. The full piece is worth reading but I don’t think I should quote it to you. Let me say it this way: Yamamoto was deeply concerned with success and failure, having seen both in his life. As a masterless samurai, he was trying to get the young samurai to see that it’s not winning or losing that count so much, as how you play the game.

I can’t help but intertwining those ideas with Lao Tze’s, here. He is concerned with keeping death out of the body, but for Lao Tze, death may as well be what Yamamoto was calling failure. If you live the right way, failure cannot touch you. Perhaps, failure cannot touch you because you are a great success, or perhaps it cannot touch you because you are a complete blockhead who never recognizes defeat.

I interpret this chapter as saying, in so many words, “don’t worry about it.”

Marcus:

Or, “Shit happens. Don’t worry, be happy.”

Caine@#1:

“Shit happens. Don’t worry, be happy.”

Try, anyway.

One of the things I’ve realized from much thinking about these things is that our attitudes are a choice. It’s not that “a positive attitude will help you!” or anything like that but we do choose, to a degree, our responses and being upbeat is an equally valid choice with being miserable. (i.e.: it doesn’t make a whit of difference except to us)

Japan is such a conundrum. On the one hand there’s the incredible beauty and delicacy of Japanese art and philosophy, yet on the other is the fanatical, brutal savagery of militarism (as demonstrated all too clearly in the early-to-mid 20th century).

Tojo’s Japan was no less horrific than Hitler’s Germany, and no less responsible for its own downfall. An example: in the battle of Midway, the Japanese officers quite literally preferred death to the shame of defeat. Three of the skippers of the doomed carriers chose to go down with their ships even though they could have simply evacuated along with their crews. (The fourth was killed during the attack, and one of the three who chose to die didn’t because he was given a direct order not to.)

In other words, failure could not touch them because they died.

DonDueed@#3:

Japan is such a conundrum. On the one hand there’s the incredible beauty and delicacy of Japanese art and philosophy, yet on the other is the fanatical, brutal savagery of militarism (as demonstrated all too clearly in the early-to-mid 20th century).

Well said.

One of the things I believe about Japanese art is that it’s so good because they work so hard at it. When you think about the absurd amount of work that goes into making one of those little tea cups, or a samurai sword, or … pretty much any Japanese art, the common characteristic seems to be “do it as hard as possible.” If there are nails: hammer them in with your forehead. If there are raw materials: start with sand and hammer into something else. Etc. It’s a special kind of crazy, and the results really are worth it – mostly because the viewer is thinking “thank god I didn’t have to do that.”

failure could not touch them because they died

Exactly. And they did not have to acknowledge failure because, after all, they died trying.

My experience is that when shit happens, I cannot just choose to be happy. It doesn’t work that way. I’m going to be sad or angry or whatever, and I cannot just think happy thoughts and make the bad mood go away. However, I can influence how I feel in a more subtle way. I first found this out after my totally disastrous first relationship. The whole thing went totally wrong, and for a week or two I was totally gloomy. Ultimately, I got sick of feeling depressed and simply tried doing things I enjoy. I went on some trips, participated in events where I could meet people and make new friends. It turned out that spending a couple of days doing things I enjoy was enough to make me perfectly happy. While I cannot just choose to be happy, I can choose to do things that I enjoy, and that works to make me happy.

It’s also possible for me to choose how I view my experiences. I can think, “This experience sucked, I suffered,” or I can think, “Well, this was a valuable experience, at least now I have learned what things not to do.” The second option helps to avoid feeling miserable.

Personally, I’d rather acknowledge failure than die for a stupid reason. There’s nothing glorious about a pointless death.

Incidentally, acknowledging failure is an essential skill. For example, when politicians start noticing that some program isn’t working, they should terminate it rather than continue pouring more money into it.

I disagree. Even the most successful person has experienced hundreds (if not thousands) of small failures. For example, how many shitty paintings do you think somebody has to make before they acquire the kind of skills Bouguereau had? And even if you are successful in this one area, there are going to be other different skills that you will lack.

And being a “complete blockhead who never recognizes defeat” is plain stupid. If you mess something up, acknowledge it, learn from your mistakes, and try to do better next time.

The only way how you can ensure that “failure cannot touch you” is by not doing anything. That’s possible only if you have no hopes, no dreams, no aspirations, if you just don’t care about anything you do.

And being a “complete blockhead who never recognizes defeat” is plain stupid.

I was obliquely referring to Trump. Who appears to be a complete blockhead who has been tremendously successful by being .. a complete blockhead.

Well, yes, he’s been successful and he got elected as a president. And being oblivious to criticism ensures that he stays happy. But simultaneously he’s also the laughingstock for the whole world. Personally, I wouldn’t like to experience this kind of success.

I’ve been reading some of Marcus Aurelius’ writings* and one of his points is much the same. According to him one should cope with the good and bad alike as best as one can with the means available. Above all, burdens should be borne … stoically. The soul (or mind, if you prefer) shouldn’t wallow in misery since there is no point to it. He was a stoic so that attitude is hardly surprising. He was also religious and thought that noone was given a fate they could not bear. But even when considering a godless universe – it’s all just atoms** – he seems to reach the same conclusion.

In his mind the “natural state” a reasonable being* ought to strive for is one where it is not swayed by strong emotions or wordly concerns such as wealth or fame. The latter are too fleeting to be worthwhile anyhow. As for strong emotions, I think he felt they might interfere with one’s judgment, which could not be allowed since one ought to be just and do good where one could.

Regarding the “Love of Life”, the acceptance of death is also a major theme in Aurelius’ writings, or at least those parts I’ve been presented with. Life is so brief that years, decades or even centuries of life would pale into insignificance against the time before and after. Death ought to be embraced, whenever and however it came. Everything living and dead continuously changes, rots, is reabsorbed into the whole,**** and refashioned into something else. That, too, is part of the natural state of all things. The only exception might be the soul, which might or might not dissolve. Stoics were apparently divided on the matter of an eternal soul and if Aurelius expressed a firm opinion I haven’t seen it or missed it.

—

Too many footnotes!

*Disclaimer: I´m paraphrasing my understanding of works from centuries ago that were translated (who knows how often) into another language and am no wordsmith. The results are rather coarse.

**Not that different from his religious view, though. The only real difference between the two worldviews seems to be the lack of a soul and an ordained fate, but that may be my shoddy interpretation.

***A very rough translation of mine. In his writings he distinguishes between animals and humans. Both are driven by basic instincts and needs that should be heeded, but humans also have a soul or mind that places them above animals, plants, etc. However, this also gives them a responsibility to use the capacity for reason they have been given.

****Aurelius (or the translator in his place) referred to what we now call “universe” as the “state”, which is interesting to me as a point in terminology. He was referring to “the whole”, a big organised something, with what I suppose was the most relateable term for something of this nature available at the time. Although this does make me wonder how exactly the word “universe” is relatable to anything in current human experience.

komarov@#8:

Above all, burdens should be borne … stoically

My dad named me after him. One time he observed that “it’s a lot easier to be a stoic when you’re emperor of the known world.”

He was also religious and thought that noone was given a fate they could not bear.

Substitute “Tao” for ‘fate’…

It seems to me sometimes that humans use “the soul” as a means of claiming that we are special; a lot of bad ideas depend on a presumption of human specialness.

Life is so brief that years, decades or even centuries of life would pale into insignificance against the time before and after. Death ought to be embraced, whenever and however it came. Everything living and dead continuously changes, rots, is reabsorbed into the whole,**** and refashioned into something else. That, too, is part of the natural state of all things.

That sounds very Epicurean. Of course, Aurelius (being emperor!) was well-educated and would have had ample opportunity to encounter many philosophies. Here’s a thought: he’d have had a copy of Lucretius De Rerum Naturae if he wanted one. Now that would be a rare book indeed!

Indeed that must have helped quite a bit, and he was aware of this, too, I think. In his early writings he expresses gratitude to a lot of poeple: his benefactors and adoptive parents and long list of teachers. But he was also grateful – to fate, I suppose – for having the means to do do so much good, that he could afford to be generous without having to give it a second thought.

He was eager to learn from his teachers and very keen on philosophy from an early age. In some passages he expressed regret that, being emperor, he could not afford the time to read all those wonderful books he might have access to. He sounds almost envious of his adoptive father and predecessor Antoninus, who nevertheless managed to spend a lot of his time reading.

Regarding the distinction between animals and humans, I believe that was (and perhaps still is) a common view, but I don’t think it was as absolute for Aurelius as it was, for example, in Christianity. Humans may be “higher” but only due to their capacity for reason. Should they refuse to use their gift, they are no better than the “lower animals”. Not exactly in tune with a naturalistic worldview but not the worst way to go. To my mind he seems to at least imply a certain responsibility towards other creatures, rather than simply placing humans higher up on the ladder so they may do as they please with everything below. But that is just my interpretation. At any rate the emphasis is always on reason, rather than worrying about the details of hierarchy. (Maybe another side-effect of being emperor is that rank is less important.)