… was when he went through the mouth of Hell.”

Not everyone loved Andrew Carnegie. But that’s alright because Carnegie loved himself enough for the rest of the world, combined.

[source]

Carnegie and Frick’s partnership was profitable and antagonistic; the two men screwed each other back and forth using various corporate board-manipulation tricks, buying out rights of first refusal, and (this might sound familiar today) adjusting the value of their companies by telling the government what to place protective duties around, and what not to, and when. Carnegie and Frick were the prototype that every subsequent rapacious capitalist followed – young Andrew, the penniless immigrant from Scotland, starting with $20 in stock in a railroad and parlaying it into a fortune that would be about $500 billion in today’s dollars. At the end of his life he appeared to realize that he was a hateful son of a bitch, so he re-invented himself as a philanthropist by giving away much of his fortune.

Frick, also a penniless immigrant, eventually owned the coke-making process that Carnegie’s steel company used – their relationship was based on an ill-advised agreement in which Frick offered Carnegie coal at a set price/ton ($1.63) in spite of what happened to the market; coal subsequently soared to $3+/ton and Carnegie still made Frick very rich indeed, since his company was gobbling coke at a crazy rate. This was in the 1890s, when coal mining was also in its heyday, and steel production was, too: Pittsburgh, alone, produced more high quality steel than all of the other sources in the world, combined. Its daily output was what Japan produced in a decade – World War II in the Pacific theater was not a foregone conclusion. Carnegie and Frick did not really invent anything new, in business terms – “buy low, sell high” is the obvious one. But “mind the bottom line” is the other: both men realized that if you control the bottom line price, you can survive and flourish by keeping your costs constant and selling your product when the markets spike.

This began the era in which labor got utterly screwed, over and over. Because Carnegie and Frick controlled the means of production (as Marx, who began writing Capital around this time, would say) they could tell laborers “We can only pay you this much per ton or we’ll have to close down the factory.” Laborers were not a mobile work-force and Pittsburgh was where the work was: Carnegie would push down the labor costs and keep selling steel at the top-line cost. He had the preferential agreement with Frick that allowed him to manage the bottom-line cost of coke, too. And, for a while, that was OK with Frick because he could use Carnegie’s fixed price as an excuse to push down the bottom-line cost for labor. That way, Carnegie’s deal really didn’t matter to him – if he could get mine-workers to accept $.04/ton less for coal, that was the same as getting Carnegie to pay $.04/ton more for it.

Labor, naturally, unionized and struck and complained. But it didn’t matter: Carnegie and Frick had the government in their pocket. During the “Battle of Homestead” Carnegie built a huge wall around the steel mill and locked the laborers out, then hired 300 armed Pinkertons’ men to come guard the building. The workers fought, and the Pinkertons’ lost – around a dozen men died on each side – until the Governor brought in the National Guard, who broke the strike. Laborers were charged with assaulting the Pinkertons’ men. All of these shenanigans were the formation of the American industrial system: built on the muscle and sweat of laborers, a few office-workers assembled vast fortunes by manipulating prices just a little bit.

For example, there was a bonus that Carnegie agreed to pay the union for steel production over and above a set amount – some number of pennies per ton. Tons matter when you’re talking about steel: this was a lot of money, some years, as America’s appetite for steel increased and increased and increased. So, Carnegie went back to the unions and said, basically, “I am paying you too much in these bonuses. We must re-negotiate because I am not making as much money as I want this way.” Carnegie played games with the unions, too: they would calculate the per-ton bonus based on production demand in December, the least busy month of the year. A few cents per ton made no difference to the workers – they were barely able to make ends meet – but it compounded into a vast fortune for Carnegie. Frick played the same sorts of games on the coal miners.

We don’t know if Marx wrote Capital specifically thinking of the screwing that US steel-workers were getting, or not – but Marx’ entire exploration of the theory of commodity value is intended as an answer to the questions that are raised by Carnegie and Frick’s industrialism: is not the “profit” of a business really the theft of surplus production? How much can the owner of the steel mill claim the mill is worth in terms of the ability for the laborers to turn cheap ore into valuable steel? What is a reasonable amount of profit (rent) for the mill owner to take in return for the workers burning their lives away in a toxic hell? These are serious questions.

They are questions American Capitalism has never tried to answer; all they did was demonize Marx and assert that it was their duty to the shareholders to maximize their profits. That was a maneuver Carnegie would have thoroughly approved of (in fact, he arguably invented it) because he was the biggest shareholder of them all and he quite believed in his duty to extract as much money from the workers and the customers as was possible. Like a modern-day libertarian or a 1950s objectivist, Carnegie promulgated The Gospel of Wealth,[wik] which was a sort of calvinist-style propaganda-piece that could be shortened to “I got mine. I must be pretty special, huh? PS – fuck you.”

They are questions American Capitalism has never tried to answer; all they did was demonize Marx and assert that it was their duty to the shareholders to maximize their profits. That was a maneuver Carnegie would have thoroughly approved of (in fact, he arguably invented it) because he was the biggest shareholder of them all and he quite believed in his duty to extract as much money from the workers and the customers as was possible. Like a modern-day libertarian or a 1950s objectivist, Carnegie promulgated The Gospel of Wealth,[wik] which was a sort of calvinist-style propaganda-piece that could be shortened to “I got mine. I must be pretty special, huh? PS – fuck you.”

He was. He was a rapacious bastard who would have shocked Crassus with his lifestyle and embarrassed Genghis Khan with his greed. Carnegie would look at what is going on, today, where US manufacturing has been exported to the 3rd world and China in order to game the labor market, and drive prices down, and smile. He’d probably appreciate the bullshit artists who say they are going to bring back coal jobs, too. Except, once he was done elevating himself, he never would have been seen in such declassé company.

Here is a bit from Meet You in Hell:

Balanced against the feelings of workers subjected to such rigors and dangers were the positions taken by Carnegie, Frick, and their superintendents. In response to questions posed by a congressional committee of inquiry, John Potter, superintendent of the Homestead works did his best to make management’s case:

Q: You say the workmen at the mill can turn out twice the product by reason of the improved machinery?

A: Yes sir.

Q: Than any other mill in the world?

A: Yes sir; of the same character.

Q: What do you mean by the same character?

A: The same class of mill.

Q: Well, if there is no mill like it in the world there is no other same class?

A: That is right.

Q: The labor cost of turning out that product at that mill would be one-half what it would be anywhere else where they are paying the same wages?

A: I do not know whether that is true or not.

Q: Does that not follow as a necessary result? You stated that with your machinery there the men could turn out twice the product, and I ask the simple question whether, if that is true, the labor cost of that product would not be one-half that of any other mill having the same rate of wages?

A: I do not think it would.

Q: … What kind of machinery is there which increases the facility of labor?

A: Automatic machinery, hydraulic, etc.

Q: Is that the machinery of which there is no mill possessed?

A: We use hydraulic machinery to a greater extent than any other mill.

Q: Then the use of machinery actually reduces the cost of the product, does it not?

A: Well, it should do it; that is what we want it to do.

This discussion was taking place because Carnegie had (through intermediaries) been pushing Congress to put protective trade tariffs in place, to keep foreign steel from being able to enter the market at all.

Those were the glory days of American industrial capitalism. Over 800,000 people we employed by the steel mills. That huge labor investment also pulled an entire supply-chain along with it: coal, then oil. Those jobs are gone, now, because the capitalists kept squeezing more and more profits out of the businesses until it got to the point where it was cheaper to just have the entire business in China, and make the profits at the headquarters-building in New York.

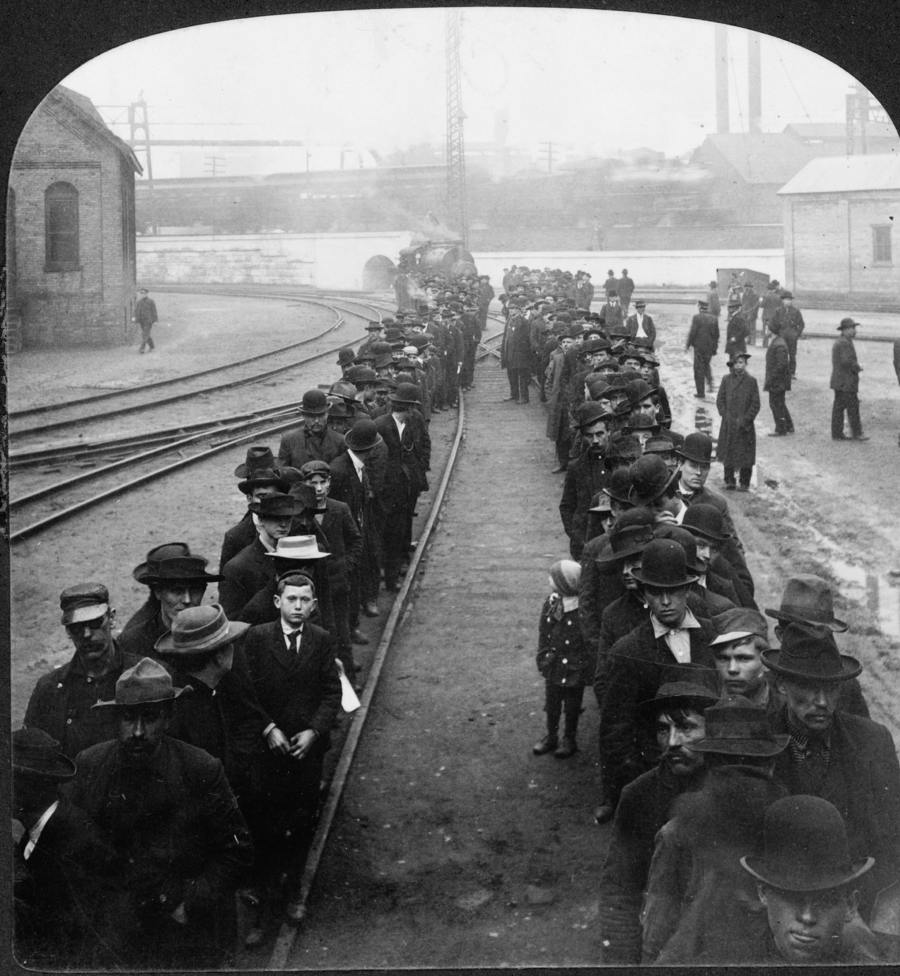

“American jobs” created by Carnegie and Frick in the 1890s were not really “American” anyway. In order to push labor costs down, and have a ready pool of alternate laborers, Carnegie and Frick imported hungry, uneducated, desperate Europeans from Poland, Ukraine, Russia, and elsewhere. The history of labor is the history of immigration. The history of American hatred of immigrants is the hatred of the first victims of Carnegie and Frick having come to terms with their situation, and resenting the people that were brought in to drive their wages down and down. They should have seen that coming, and risen up and killed Carnegie and Frick. One of Emma Goldman’s associates tried: a young anarchist from New York came down and shot Frick. As Frick lay incapacitated the assassin walked over to put a bullet in his brain, but his gun failed to function. He was cocking it for another shot when a loyal man-servant clobbered him from behind with a hammer. I always wondered whether the man-servant would have done otherwise, had he time to think it over.

Now, American Jobs are exported to China, where laborers work for depressed wages in industrial-age conditions. While American capitalists like Apple congratulate themselves for making vast fortunes, they’re just living the path blazed by Carnegie and Frick: gaming the labor-cost and driving the bottom-line down, so they can pocket hugely disproportionate top-line profits. Today, they line up to work at Foxconn, but what’s the difference? Somehow, there is a small percentage of the world’s population who have figured out a way of tricking the vast majority of the population into working every day for their happiness and luxury. What is the next Gospel of Wealth that will be written? I hope they translate it from the Chinese, but it’ll be bullshit anyway.

Bessemer steelmaking was not for the faint of heart, as Sir Henry Bessemer himself made clear: “The poweful jets of air sprint upward through the fluid mass of metal. The air expanding in volume divides itself into globules, or bursts violently upward, carrying with it some hundredweight of fluid metal which again falls into the boiling mass below. Every part of the apparatus trembles under the violent agitation thus produced; a roaring flame rushes from the mouth of the vessel, and as the process advances it changes its violet color to orange, and finally to a voluminous pure white.

During the process the heat has rapidly risen from the comparatively low temperature of melted pig-iron to one vastly greater than the highest known welding-heats; the iron becomes perfectly fluid, and rises so much above the melting-point as to admit of its being poured from the converter into a founder’s ladle, and from thence into successive molds.

Tending to the Bessemer process was an arduous if spectacular endeavour, often leading to fatalities when converters exploded from heat or overflowed; however the open-hearth process could be even more dangerous, requiring considerable endurance and physical dexterity from workers as they braved intense heat to dump additives into the enormous vats of molten metal. More than one worker had tumbled from an overhead catwalk into a pool of red-hot steel, “creating his own mold” as it was said, and countless others were burned and blinded by flying spatters.

pay line at homestead, Pa. 1907

Sometimes, we remember the 8-hour workday as being a hard-fought battle that labor struggled to win. Steel mills are expensive to shut down, so they ran constantly; the initial labor shifts were 12 hours on, 12 hours off. Laborers died, literally, of exhaustion. The 8-hour day is simply changing 3 shifts of labor for 2. The companies fought this, naturally, but in the end they just adjusted the pay to be hourly, and preserved their profit-margin by paying the laborers less. When automation and better industrial efficiency began to come online, they reduced the size of the work-force, but kept paying them hourly – so the profit margins soared as the labor costs dropped.

When you look at what happened to the US automotive industry, where labor was slowly backed into a corner by companies that kept shrinking the labor needs with automation, you can see the future of global industrial capitalism: the jobs will move to where there is the least regulation and they can screw the workers as hard as they possibly can. There is nothing we can do prevent it, either, since the capitalists are the government, and nobody can stop them (strikes won’t work since they will just replace people with robots and fire everyone.)

The future looks like the gig economy. Carnegie would smile benevolently from his slag-pit in hell.

He would if he were in hell; which as an atheist, he didn’t believe in.

link

Reginald Selkirk@#1:

He would if he were in hell; which as an atheist, he didn’t believe in.

Carnegie was complicated. He appears to have had a nearly calvinistic attitude about the exceptionalism of hard-working people – he believed that with a near-religious fervor, because you really need that kind of fervor to believe that. His Gospel of Wealth depends a great deal on denying the reality of his own experience: he did not work hard and was not rewarded as a result of his hard work. He was rewarded for finding a way to interpose himself in a value-chain and charge rent, basically. Yet he seems to have convinced himself of the virtuousness of that… Maybe he was an atheist but his religion was himself? I don’t know. I also see the echoes of christian fear of punishment in the afterlife, in his actions as he was getting closer to dying. He did not have (that I am aware of) a well thought-out and published humanistic set of reasons for his philanthropy. It sounds like he was either showing off, or maybe there were some residual afterlife myths haunting him.

All that said, he didn’t need to lie about anything. Anyone who would disagree with him, he owned already, or ignored. I think we should be a bit skeptical about accounts of Carnegie from any sources that were close to him or the family – when he reinvented himself as a philanthropist, he had to thoroughly bury the battle of Homestead (he blamed Frick, naturally!) and somehow had to square in his mind the idea that he was importing cheap immigrant labor in order to crush the unions and keep labor from profiting from their work – basically robbing the workers blind and convincing himself it was, what? God’s will? Today he would be a libertarian.

I just don’t get billionaire philanthropists. If they cared about the wellbeing of other people, they could start by paying their workers fair wages. And if they did that, they couldn’t earn so much and they wouldn’t become rich in the first place. A billionaire who cares about the wellbeing of other people is inherently impossible.

No, workers (servants, slaves, whatever you call them) have been screwed over for millennia.

Whenever I read about the misery experienced by poor people, I wonder why such a life is worth living in the first place. I hated even a 40 hour work week in a reasonably decent job. It felt like I didn’t even have a life (so little free time to do things I actually enjoy!). As the French say: “métro, boulot, dodo.” I think I’d just commit a suicide if my living conditions ever became as awful as those experienced by impoverished workers. What can you possibly hope for when life is so bad? Make some babies hoping that they will get education and have a better life? Well, statistically that’s unlikely to happen. What’s the point of all this suffering? If humans cannot have happy lives, in my opinion it’s better to just stop breeding and die out.

I guess the prevalence of factory suicide nets seems to indicate that some people agree with me here.

Once work gets automated, manufacturing goes to wherever there are 1) smallest taxes, 2) worst environmental protection laws, 3) cheapest energy and raw materials. And nobody can prevent this. The problem is that all the countries on this planet would have to agree upon enforcing strict environmental protection regulations and agree not to make tax heavens and to enforce decent minimum salary requirements for the workers. If even a single country fails to do so, that’s where all the companies will go.

And, frankly, it looks like countries are trying to outcompete for the honor of being the worst in this regard. In USA this crap happens even on a state level with states competing over creating the most favorable conditions for businesses to relocate to. This results in tax breaks for the rich with taxpayers and employees paying for it.

It seems for me like there’s a correlation: the harder a person works, the less they earn. It’s always the poorest people who work over 12 hour shifts in miserable conditions that damage their health. I have never seen a rich person work in toxic sludge for long hours. This whole idea that rich people are hard-working is bullshit. It wasn’t Carnegie who worked hard; the employees who endured 12 hour shifts in steel mills were the hardworking ones.

My answer: not much. Owners, CEOs, shareholders etc. aren’t working harder than the employees, so why should they be earning a lot more?

There are always exceptions. Henry Ford did just fine after deciding to pay his workers a living wage.

Reginald Selkirk @#4

In my comment I talked about fair wages. There is a big difference between a fair wage and a living wage. Just because a worker can survive without suffering awful poverty and worrying how to make ends meet doesn’t mean that their income is fair.

The history of American hatred of immigrants is the hatred of the first victims of Carnegie and Frick having come to terms with their situation, and resenting the people that were brought in to drive their wages down and down.

Such realizations and resentments go way back before mass immigration from eastern Europe. Back circa 1830, when strong backs and small brains were in demand for the canal-building craze, boyos fresh off the boats from Ireland would gang up by home counties and murder each other en masse for opportunities to swing shovels all day for less than a dollar (unless lucky enough to get relieved permanently from such tasks by landslides (in which cases the widows received the pay due for that day’s sweat)).

[OT]

Real machines producing abstract goods, in these early years of C21, but I imagine the featured attitude still thrives.

https://cseweb.ucsd.edu/~mbtaylor/papers/Taylor_Bitcoin_IEEE_Computer_2017.pdf

(From a comment on Charlie’s Blog)

Ieva Skrebele @#3, and especially #5:

I’m afraid your logic is a bit circular here. You seem to be defining a fair wage as one that does not permit the capitalist to become rich; it is them a tautology that billionaires do not pay fair wages. I don’t like that for two reasons: firstly, it’s not a useful definition: it presupposes that profit above a certain limit is bad. Let’s state that assumption explicitly, and talk about it (I would not disagree completely).

Secondly, there are rich people who got their billions in other ways than stealing them a few cents at a time from their countless workers’ wages. It is difficult to argue that Microsoft, for instance, pay their employees unfairly — unless, again, you’re of the “profit is theft” persuasion.

There are always exceptions. Henry Ford did just fine after deciding to pay his workers a living wage.

Only because the auto assembly lines were so miserable, and there were alternatives (unlike a Pennsylvania mill town) that he HAD TO?

cvoinescu @#8

I was fully aware of the circularity; after all, it was intentional. I never defined a fair wage as one that does not permit the capitalists to become rich. It’s just that “capitalists cannot get rich” is an inevitable side effect of the way how I define a “fair wage.”

I’m perfectly fine with some income inequality. Sometimes it’s fair. If one person works 50 hour weeks but their colleague works part-time, it’s only fair that the person who works longer hours earns more. Some jobs require more education than others, therefore it’s fair that those employed there also earn more—after all their larger earnings must compensate for the time and money spent on education. And some jobs are simply more pleasant than others. It would be fair to earn a larger hourly rate when working in some unpleasant job.

What I perceive as unfair is when the CEO earns thousands of times more than the person who is sweeping floors in the CEO’s office. It’s physically impossible for one person to work thousands of times harder than others. I have heard people suggesting law proposals, which would enforce that within a single company the highest-paid worker never makes more than 10 times the wage of the lowest-paid worker. If that happened, I would perceive this as fair. But currently in most companies this ratio is over 100-to-one, and this, in my opinion, is not fair. Every worker in a company is necessary in order to earn the profits, after all, producing something of value is a team effort. Why should one member of a team be more privileged than others?

Under my definition it would be possible for self employed people to get rich. It would also be possible for small businesses to ensure that every single person working there gets rich. It wouldn’t be possible for anyone in Microsoft to get rich. According to Wikipedia, Microsoft has 124,000 employees. The moment you divide profits fairly among so many people, it’s impossible for any of them to become a billionaire.

Incidentally, the moment a self-employed person starts earning millions, you can start wondering about whether they are charging a fair price for whatever it is they are selling. Maybe they are just ripping off their customers? But that’s a whole different discussion.

Moreover, we can also look at whether it’s a fair society when some people are significantly richer than others. Incidentally, I don’t think it is, so I’m definitely in favor of a progressive income tax.

Mu attitude is significantly more nuanced than “profit is theft,” but probably I’m quite close to thinking so. After all, often profit really seems like legalized theft for me.

Ieva Skrebele @#10:

I mostly agree with you, and yes, “profit is theft” is a caricature; “excessive profit is theft” would be a perfectly reasonable view.

You say: Every worker in a company is necessary in order to earn the profits, after all, producing something of value is a team effort. Why should one member of a team be more privileged than others?

That is not a rhetorical question. One popular answer to that is used to justify huge income differences. The persons sweeping the floors are largely interchangeable; almost anyone can do that job, should they want to (but see note 1 below). The success of the company does not hinge to any significant extent on how well the floors are polished. The programmers are much less interchangeable: practically all have gone to college, some have experience, some have specific skills, which may be rare; and even with studies and job experience, not everyone could do that job (but see note 2). You can fairly attribute a good chunk of the success of the company to good, hard-working programmers. It’s even harder to find the right people for division leads, architects and other high-level technical and managerial roles. For all the hard work of the rank-and-file, if you screw up at this level, you end up with Microsoft Bob (also note 3). This is so far more or less common sense. Where it gets really dubious is when you extrapolate this reasoning to the value of the CEO. A CEO can make or break a company, so it makes sense to pay a good one extremely well, right?

My problem with that argument is twofold: “extremely well” does not have to mean the batshit excess commonly seen (but I acknowledge that the value of having this specific CEO can well be many times more than having this specific janitor, so a 10:1 cap may be too egalitarian). But my main complaint is that it’s largely the leadership who decide how valuable the leadership is, and it’s them who evaluate their own performance. Which is why bad CEOs still get paid a metric fuckton of money for driving their companies into the ground. And that is unfair in the extreme. It really sucks. And I don’t have a good solution for it (except pack up and move to Badgeria, I suppose).

Note 1. “Should they want to” hides a huge can of very well compressed worms, including racism and exploitation of, for example, illegal immigrants.

Note 2. Western countries, led by the US, are doing a great job of discouraging everyone other than reasonably well-off white men from pursuing this type of career, and then import bright people to make up the demand. This is another can of worms I won’t go into.

Note 3. Or you end up with a bro culture and chase half of your workforce away, or a number of other ills.

cvoinescu@#11:

“excessive profit is theft” would be a perfectly reasonable view.

I don’t like the “theft” comparison, and prefer to frame it as “unfair distribution of the profits” – in the case of American capitalism, it is simply assumed that the capitalists get to decide how the profits get divided out, and that they will do it unevenly because of the power disparity that comes with controlling the factory, its machinery, the company’s contracts, and customer-base. The capitalist will tell you that they earned that huge disparity because they took the risk of starting the business, with their money, and so they constitute the business as theirs. The fact that labor is never invited into a partnership – that’s conveniently omitted.

Ieva Skrebele@#10:

Moreover, we can also look at whether it’s a fair society when some people are significantly richer than others. Incidentally, I don’t think it is, so I’m definitely in favor of a progressive income tax.

That was where I was trying to go with the Badgeria idea – you can make as much money as you can in your life-time but what you don’t get to do is create a permanent class hierarchy. I’m not in favor of a progressive income tax so much as I am of a flat-out intergenerational reset. Of course that’s not going to happen. Why the younger generations are not in the streets rebelling for inter-generational equality, is beyond me.

@#13

A 100% death tax would be another option for how to solve the problem of wealth inequality and I’m perfectly fine with this option as well. Although “you can make as much money as you can in your life-time” is a bit trickier—you still need laws that protect workers’ rights to ensure that they don’t get screwed the moment some greedy bastard gets too zealous about making as much money as they can.

Is this a rhetorical question?

Ieva Skrebele@#14:

Is this a rhetorical question?

Yes. Sorry, I got carried away.