I’m not a fannish type, but I wrote a fan-letter once – to George MacDonald Fraser, Author, the isle of Man, UK. And I got back a charmingly gracious reply, too. I have read nearly everything Mark Twain wrote, and a measurable percentage of Voltaire but Fraser is the only one of my favorite authors I can claim to have completely read.

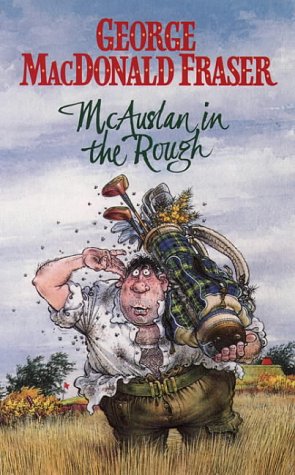

Like a lot of teenage boys in the 60s and 70s I stumbled upon Fraser thanks to the lurid parody cover of Flashman. It’s not his greatest work; I’d say Quartered Safe Out Here is, in its genre, and the McAuslan books are, in theirs. Fraser’s writing is so good it seems effortless. But, then, it would. The McAuslan books I love so much that I would type them in for you word by word, except that would be a waste of time when you can find printed paper copies much more easily. [amazon uk] It was the first book I put on my recommended reading list [stderr] so if you want to take advantage of my “satisfaction guarantee” – have at it.

The McAuslan books are military humor. A niche occupied by Spike Milligan and, ummmm… Wow, that’s a short list. “Know your niche” I suppose. Fraser served in a highland regiment on the Rangoon Road in Burma during WWII. That part was decidedly not funny, and he tells about it in Quartered Safe Out Here, which is one of the best ruminations on war I’ve ever read, and I’ve read a lot. I will eventually do a review of that, as well. Fraser’s way of writing about serious things is to make you laugh your ass off, hiccup, look at the bottom of your glass of scotch, and burst into tears. It’s not the tears of “oh… this hurts…” it’s the sudden revelation that humans really are incredibly beautiful and very goofy and noble when they want to be. Fraser’s stories sometimes make me proud to be a human; I don’t know how he does it, but I wish I did.

The McAuslan books are military humor. A niche occupied by Spike Milligan and, ummmm… Wow, that’s a short list. “Know your niche” I suppose. Fraser served in a highland regiment on the Rangoon Road in Burma during WWII. That part was decidedly not funny, and he tells about it in Quartered Safe Out Here, which is one of the best ruminations on war I’ve ever read, and I’ve read a lot. I will eventually do a review of that, as well. Fraser’s way of writing about serious things is to make you laugh your ass off, hiccup, look at the bottom of your glass of scotch, and burst into tears. It’s not the tears of “oh… this hurts…” it’s the sudden revelation that humans really are incredibly beautiful and very goofy and noble when they want to be. Fraser’s stories sometimes make me proud to be a human; I don’t know how he does it, but I wish I did.

For example, there is a story in the McAuslan series – at the end, as an envoi, about when Fraser was doing a book signing and the former commander, The Colonel, of the 92nd Gordon’s Highlanders – his former commander (who features in the books) shows up – and gruffly says, “You portrayed ‘the old buzzard’ a bit too kindly” as Fraser suddenly feels like a 21 year-old caught out on parade without his breeches, trying to remember everything he had ever called the fine old retiree standing in front of him.

Characters in the McAuslan book are so vivid they walk off the page and you feel like you might bump into them in your dreams (but never on the street): Captain Errol, Wee Wullie, Regimental Sergeant Major MacIntosh, The Pipe Major, and – of course – the snuffling “tartan Caliban” himself, Private McAuslan. Fraser has the carefully-cultivated knack of great writers, which is to sketch his characters without putting in a ton of back-fill, but after you read a bit about them, you know exactly who they are and what they will do. You know that Captain Errol, who offhandedly shoots moths on the wing with a pistol, and smokes his cigarettes using a long holder like a Hollywood star, is One Bad Dude who, when the chips are down, is such a Bad Dude he doesn’t … I won’t spoil it. But here, just feast your reader’s mind on this thumbnail of Captain Errol:

It was as I was turning to follow that I became aware of an elegant figure seated in a horse-ghari which had just drawn up to the gate. He was a Highlander but his red tartan and white cockade were not of our regiment; then I noticed the three pips and threw him a salute, which he acknowledged with a nonchalant fore-finger and a remarkable request spoken in the airy affected drawl which in Glasgow is called “Kelvinsaid”.

“Hullo laddie,” said he. Your platoon? You might get a couple of them to give me a hand with my kit, will you?

It was said so affably that the effrontery of it didn’t dawn for a second – you don’t ask a perfect stranger to detach two of his marching men to be your porters, not without preamble or introduction. I stared at the man, taking in the splendid bearing, the medal ribbons, and the pleasant expectant smile while he put a fresh cigarette in his holder.

McAuslan is the focal character of the stories, but the real hero of the stories is the regiment – Fraser keeps looping around the customs, extreme peculiarities, incidents, and responses of the highlanders to the various weird things that do happen at an advanced rate in war-time. That is what fascinates me about “military glory”: there’s something about all the horror and chaos that makes some people do really amazing things. In the case of the McAuslan stories, Fraser captures the really amazingly funny things. In an understated way that is so vivid that anyone with any imagination at all can feel the whole thing playing out like a movie in their mind.

I wish someone had gotten Fraser to record an audiobook version of these stories; there aren’t many people who could do them justice in that format, because he fills the stories with the most spectacular text renditions of various Scots brogues that manage to be: a) comprehensible to the non-scot b) unique to each of the characters c) region accurate. That latter point I am told by a genuine highlander who says that Fraser has “accomplished an amazing thing” and – he agrees – an audiobook would be a mighty undertaking and it’s a damn shame nobody sat Fraser in an armchair with recorder and some Aberlour.

Here is a bit more:

Considering his illiteracy, his foul appearance, his habit of losing his possessions, and his inability to execute all by the simplest orders, Private McAuslan was remarkably seldom in trouble. Of course, corporals and sergeants had long since discovered that there was not much point in putting him on charges; punishment cured nothing, and, as my platoon sergeant said, “He’s just wan o’ nature’s blunders; he cannae help bein’ horrible. It’s a gift.”

So when I found his name on the company orders sheet one morning after his Edinburgh Castle epic, I was interested and when I saw that the offence he was charged with was under Section 9, Para 1, Manual of Military Law, I was intrigued. For that section deals with “disobeying, in such a manner as to show a wilful defiance of authority, a lawful command given personally by his superior office in the execution of his office.”

That didn’t sound like MacAuslan. Unkempt, unhygienic, and unwholesome, yes, but not disobedient. Given an order, he would generally strive manfully to obey it so far as lay within his power, which wasn’t far; he might forget, or fall over himself, or get lost, or start a fire, but he tried. In drink, or roused, he was unruly, admittedly, but in that case I would have expected the charge to be one of those charmingly listed under Section 10, which begins, “When concerned in a fray …” and covers striking, offering violence, resisting an escort, and effecting an escape. But this was apparently plain, sober disobedience, which was unique.

With Bennet-Bruce away on a skiing course in Austria (how is it that Old Etonians get on glamorous courses like skiing and surf-riding, while the best I could ever manage was battle school and man management?) I was in command of the company, which involved presiding at company orders each morning, when the evil-doers of the previous day came up for judgement and slaughter. So I sat there, speculating on the new McAuslan mystery while the Company Sergeant-Major formed up his little troupe on the veranda outside the office.

“Company ordures!” he roared – and with McAuslan involved the mispronounciation couldn’t have been more appropriate – “Company ordures, shun! Laift tahn! Quick march, eft-ight-eft-ight-eft-ight eftwheeeol! Mark time!” The peaceful office was suddenly shuddering to the dint of armed heels, and escort and the sweating McAuslan stamping away for dear life in front of my desk. “Ahlt! Still!” bellowed the C.S.M. “14687347 Private McAuslan, J. sah!”

While the charge was read out, I studied McAuslan; he was his usual dove grey color as to the skin, and his battle dress would have disgraced a tattie-bogle. He was staring in the correct hypnotised manner over my head, standing at what he fondly believed was attention, stiffly inclined forward with his fingers crooked like a Western gunfighter. He didn’t, I noticed, look particularly worried, which was unusual, for McAuslan’s normal attitude to authority was one of horrified alarm. He looked almost pugnacious this morning.

“Corporal Baxter’s charge, sir,” said the C.S.M., and Corporal Baxter stood forth. He was young and mustached and very keen.

“Sah!” exclaimed he. “At Redford on the 14th of this month, I was engaged in detailin’ men, for the forthcomin’ regimental sports, for duties, in connection with said sports. I placed the accused on a detail and he refused to go. I warned him and he still refused. I charged him, an’ he became offensive. Sah!”

He saluted and stepped back. “Well, McAuslan?” I said.

McAuslan swallowed noisily. “He detailed me forra pilla-fight, sir.”

“The what?”

“Ra pilla-fight.”

It dawned. At the regimental sports one of the highlights was always the pillow-fight, in which contestants armed with pillows sat astride a greasy pole set over a huge canvas tank full of water. The swatted eachother until one fell in.

“Corporal Baxter told you to enter for the pillow-fight?”

“Yessir. It wisnae that, but. It was whit he said – that Ah needed a damned good wash, an’ that way Ah would get one.”

Some things need no great explanation. This one was clear in an instant. McAuslan, the insanitary soldier, on being taunted by the spruce young corporal, had suddenly rebelled; what had probably started off as a mocking joke on Baxter’s part had suddenly become a formal order, and the enraged McAuslan had refused it. I could almost hear the exchanges.

But it was fairly ticklish. Young soldiers, recruits, are used to being “detailed” for practically everything. Told to enter for sports, or to read Gibbon’s Decline and Fall, or learn the words of “To a mouse,” they will do these things. As they get older they get a clearer idea of what is, and what is not, a legitimate military order. But the margin is difficult to define. The wise N.C.O. doesn’t give off-beat orders unless he is positive they will be obeyed, and Baxter was a fairly new corporal.

One thing was for certain: McAuslan wasn’t a new private. He might still be backward as the rawest recruit, but he had heard the pipes at El Alamein and advanced, in his own disorderly fashion, to defeat Rommel. (God help the German who got in his way, I thought, for I’ll bet his bayonet was rusty.) And Baxter’s order should not have been given to him and he felt outraged by it. Thoughtless and zealous people like Baxter probably didn’t realize that McAuslan could feel outraged, of course.

When in doubt, grasp the essential. “You did disobey the order?” I said.

“It wisnae fair. Ah’m no’ dirty.” He said it without special defiance.

“That’s not the point, McAuslan,” I said. “You disobeyed the order.”

“Aye.” He paused. “But he had nae ——– business to talk tae me like that.”

“Look, McAuslan,” I said, “you’ve been talked to that way before. We all have, it’s part of the business. If you don’t like it you can make a formal complaint. But you can’t disobey orders, see? So I’m going to admonish you.” Privately I was going to eat big lumps out of the officious Corporal Baxter, too, but for the sake of discipline McAuslan wasn’t going to know that. “All right, Segeant-Major.”

“Ah’m no’ takin’ that, sir,” said McAuslan, unexpectedly. “Ah mean … Ah’m sorry, like… but Ah don’t see why Ah should be admonished. He shouldnae hiv spoke tae me that way.” You could have heard a pin drop. For a minute he had me baffled, then I recovered.

“You’re admonished.” I said. “For disobedience, which is a serious offense. Think yourself lucky.”

“Ah’m no’ bein’ admonished, sir.” he said, “Ah want tae see the C.O.”

“Oh don’t be so bloody silly,” I said. “You don’t want anything of the sort.”

“Ah do, sir. Ah’m no’ bein’ called dirty.”

“You are dirty,” interposed the sergeant-major, “Look at ye.”

“Ah’m no’!” shouted McAuslan, all sense of discipline gone.

“Quiet!” I said. “Now look, McAuslan. Forget it. This is just nonsense. Everyone has been called dirty at some time or another, You have, I have, probably the sergeant-major has. There’s nothing personal about it. We all have.”

“No’ as often as I have,” said McAuslan, martyred.

“Well, you must admit that your appearance is sometimes … well, a bit casual. But that has nothing to do with the charge, don’t you see?”

“Ah’m no’ hivin’ it,” chanted McAuslan, “Ah’m no’ dirty.”

“Yes, Y’are,” shouted the C.S.M. “Be silent, ye thing!”

“Ah’m no’.”

“Shut up, McAuslan!” Sergeant-major, get him out of here!”

“Ah’m no’ dirty! Ah’m as clean as onybody. Ah’m as clean as Baxter…”

“Don’t you dare talk tae me like that,” cried the enraged Baxter.

“Ah am. Ah am so. Ah’m no’ dirty…”

“Dammit!” I shouted, “This is a company office, not a jungle! Get him out of here, sergeant-major!”

The C.S.M. more or less blasted McAuslan out of the room by sheer lung-power, and heard the procession stamp away along the veranda, to a constant roar of “Eft-ight-eft” punctuated by a dying wail of “Ah’m no’ dirty.” The nuts, the eccentrics, I thought, I get them every time. McAuslan sensitive of abuse was certainly a new one.

Five minutes later, I had forgotten about it, but then the sergeant-major was back, wearing an outraged expression. McAuslan, he said, was refusing to be admonished. He was demanding to be taken before the Commanding Officer.

That particular story goes on to a spectacular ending that is courtroom drama better than anything you’ve ever seen on television. There are about 30 stories in the entire collection, about 550 pages in total. I’ve given out many copies, including one to a retired French general, who said he nearly choked to death laughing about Bo Geesty, and was pretty sure he’d served with some of the characters in the book.

I just wish that there was an edition with suitable and great illustrations. Thomason, the artist who did the sketches in my favorite edition of Marbot, [stderr] or Bill Mauldin (who I am absolutely sure would have loved this book) could have nailed it.

Just read it already.

I did a consulting project back in 2003 and my point of contact was an older guy who had been a Command Sergeant Major in the US Army. That’s pretty big stuff as non-commissioned officers go. Naturally, I gave him a copy of McAuslan and he called me about a month later and told me about how, one year, his unit was doing REFORGER maneuvers in Germany and he’d had to liaise with a highland regiment. Apparently, he scheduled a meeting with his closest peer, who happened to be the Regimental Sergeant Major of The Gordons. As he told me, he got all spiffed up because he felt he was going to be representing his unit as best he could, went to the meeting, walked around a corner and “slammed face-first into a great mountain of Scottish” – the R.S.M. of The Gordons. The sucessor of R.S.M. McIntosh, who appears several times in McAuslan. Let’s just say that the R.S.M. of any highland regiment is a really imposing thing, and walking around a corner and slamming into one is a hell of a way to get a first impression. I would sooner step on Marshall Davout’s toe.

Among the things I learned from McAuslan (and I know soccer pretty well):

In a game of association football, how is it possible for a player to score three successive goals without any other player touching the ball in between?

I can extend your list of military humor authors. As a callow youth I read Daniel V. Gallery’s fictional accounts of Boatswain’s Mate “Fatso” Gioninni. As a teen, I was enormously amused. I’d not recommend them unreservedly, though. Later in life, I better understood more discomfiting elements, as the stories are a product of their time. For instance, with the cold war and Vietnam as context, there was contempt expressed for college students (i.e. those exempted from the draft).

Some Old Programmer @2: Fraser was an old-style Tory who probably would have harrumphed in agreement with Enoch Powell over a scotch and soda. His attitudes about race, class and Empire seep through the Flashman and McAuslan stories. I haven’t read his memoirs, but I’m guessing they’re pretty clear in those as well.

All that said, I still love those stories. As good as P.G. Wodehouse, IMO.

And what, pray tell, has any of this to do with (which?) O’Brien’s lower intestinal condition?

Pierce R. Butler @4: It has to do with how McAuslan heard “the constellation of Orion”, IIRC.

Rob Grigjanis@#3:

I haven’t read his memoirs, but I’m guessing they’re pretty clear in those as well.

He was not as conservative as one might expect. It was a relief to see that Flashman was a parody, not wish-fulfillment. He has some places in Quartered Safe Out Here where he harrumphs a bit about the controversy surrounding the US use of nuclear weapons on Japan and takes on the topic from his usual very personal angle – after all, he was fighting in Burma at the time. But he’s fair and his knowledge was limited. He was generally skeptical and sarcastic about the deeds of government, so he wasn’t a fascist with training wheels. Fraser seemed to simultaneously see the best and the worst in people. To be a proper conservative one must see the best in one’s own people, and the worst in others.

I’ve never searched out any of his newspaper writings and now I suppose I should.

Pierce R. Butler@#4:

I was trying not to spoiler it, but now I suppose the cat’s out of the bag.

The constipation of O’Brien is the stellar formation that a bunch of highlanders attempt to use as a navigation marker in a night maneuver exercise, which McAuslan manages to accidentally bring to a spectacular denouement while attempting to relieve his bladder.

Addendum to my #6:

In his memoirs, Fraser is not at all classist or racist (though he has some trenchant things to say about the Japanese) so I believe that Flashman’s classism and racism are parodies. There are many opportunities for him to describe the gurkhas or indians or lower class scots he interacts with, yet he unfailingly reaches in and illuminates the best of them, which Harry Flashman would decidedly not have even seen.

I plan to eventually review Quartered.

Some Old Programmer@#2:

I’ll look for them!

Marcus: After I started reading the Flashman books, I didn’t initially see Fraser as being particularly conservative. But while Flashman was a parody, I eventually got the distinct impression that Fraser thought the Empire was a Good Thing, and that Kipling had it right.

There’s also a rather condescending attitude towards the lower classes, which I think is fairly evident in the McAuslan stories.

PS the title of Quartered Safe Out Here is from Kipling’s Gunga Din.

I was going to mention Kipling and Bill Mauldin as military humorists. Fraser is able to make me feel like I understand what’s going on. Even in the Flashman books, I end feeling that I understand the background history better than I did before. I haven’t read off of Frasers work yet, but I add another to my list whenever I finish the one I’ve got.

I haven’t read Kipling enough to find humor in it. That sounds like an oversight on my part.

I do not think George MacDonald Fraser was in a Highland Regerment until he was in North Africa. Wiki says he was in the Border Regiment while out the Burma Campaign.

jrkrideau@#13:

he was in the Border Regiment while out the Burma Campaign

Yes, that’s correct. I got confused because while I was reading the bit from McAuslan, there’s the story of his taking the officers’ candidacy exams and they are also mentioned in Quartered Safe Out Here and I brain-farted. It’s one of those things that I “knew” but managed to mis-remember anyway.