I’ve always loved knives and swords – since as long as I can remember. When I was a kid I wanted to forge samurai swords. It wasn’t until much, much later that I learned that some things are outside of your scope, unless you grow up in the right time and place (in which case, being a sword-smith is probably “meh” to you…)

The availability of modern tools and a better understanding of metallurgy has made it much easier to do laminated blades – though contrary to the legend of Bill Moran figuring out how to do “damascus” all over again – the process was never lost. (And there are multiple processes that go under the same name.) Anyhow, nowadays there are some really great, affordable, pieces made using powdered steels and CNC cutters – it’s possible to get what would be a legendary blade for under $100.

Unfortunately, success breaks open new markets, and sometimes closes others. For a short while, Jantz Supply carried Japanese-style blades out of VG-10 cored stainless steel damascus, unmounted in various configurations. I used to grind my own blades but it was immediately obvious that they were better than I could do (and stainless is no fun to polish!) so I laid in a goodly supply, and for several years my various friends got cooking knives on random occasions. One of my friends had an “oops” in which a kid managed to crack the tip off a Japanese-style paring knife I made for him, so I took the knife back and re-ground the back and re-polished and sharpened it. Then I thought I’d refinish the handle, and while I was at it, I decided to make a matching cleaver for him. I had a spare cleaver blade left from my supply so it seemed a worthy way to dispose of it.

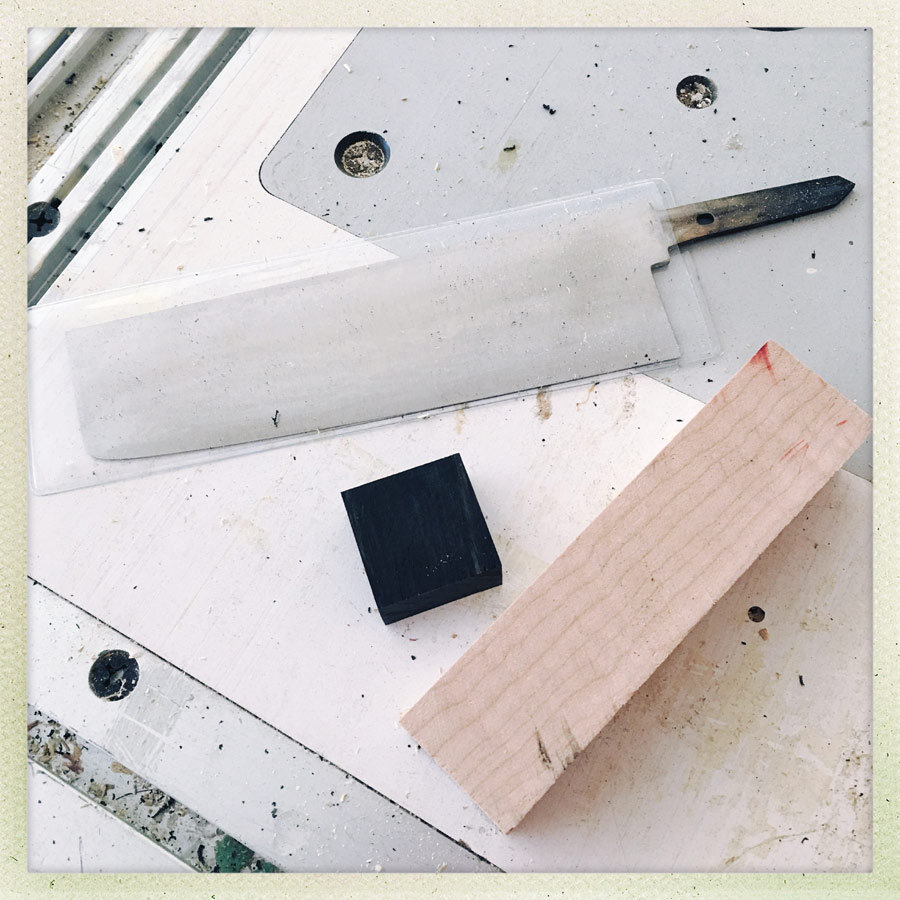

blade and wood

I have a large chunk of ebony that I bought at a yard sale in the 70s, which I occasionally table-saw a chunk off of. The maple is from a large piece of maple block I bought in the 80s; a guy I knew thought he’d make a guitar out of it and chickened out. I immediately table-sawed it up. (sssssh! It needed to be used!)

A traditional Japanese cooking knife has a paulonia/magnolia wood handle with a horn or plastic ferrule at the neck, to protect it and help keep the wood tight on the blade; the blade is just pushed into the wood and as the wood is slightly springy it more or less stays. My method of mounting inverts that process, because I’ve got a tremendous fondness for metal-reinforced resins, and I prefer a stronger mounting with exotic materials. A blade that is sunk into a block of wood, surrounded with something like stainless steel-based PC-7 epoxy: it’s going to be there forever and water won’t get in.

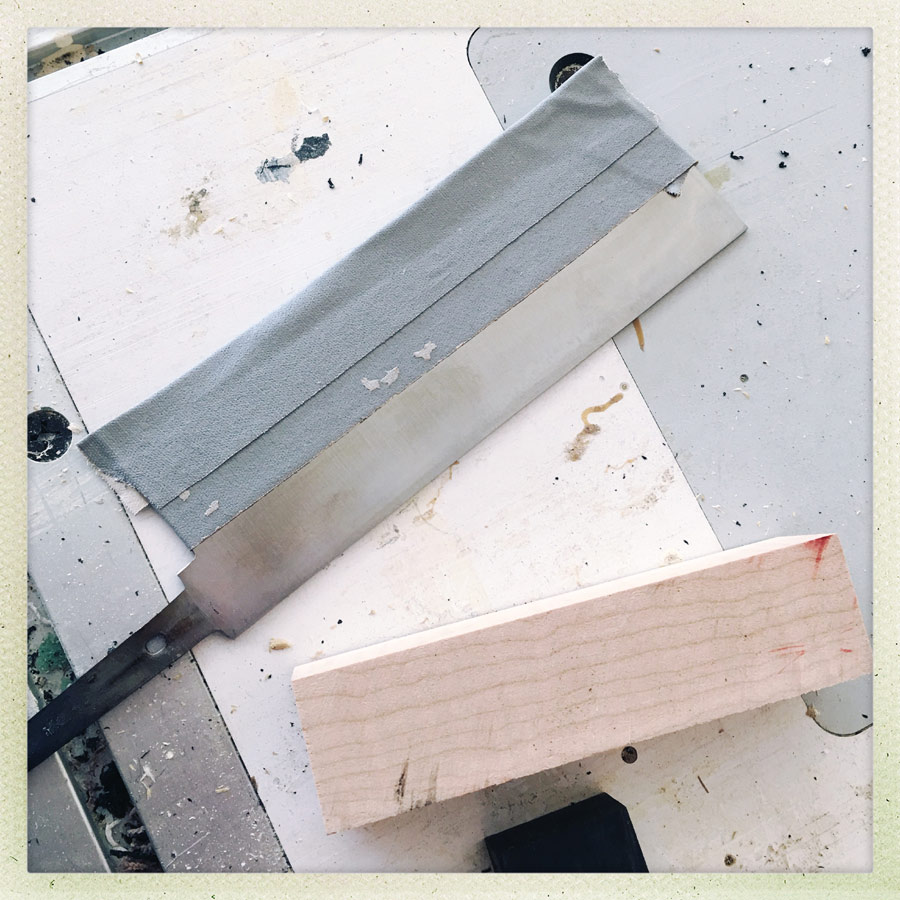

taped blade – protect the blade, and your fingers

The first step is to tape off the blade. It’s probably the most important step in the whole process. I was drilling a hole through a blade that wasn’t taped and the drillpress yanked it from my hand and I had a razor sharp blade spinning 600rpm right in front of my belly. I got below the plane of the blade and unplugged the press and the blade went right through a pegboard wall – which was a tragedy because it nicked the blade. I still have that knife, which I use as a shop-knife and a reminder.

You can see that the shoulders of the knife aren’t very cleanly cut; with the traditional Japanese mounting, it just gets hammered up against the wood so that doesn’t matter. I take a file and carefully adjust the shoulders until they look as close to perfect as they need to be.

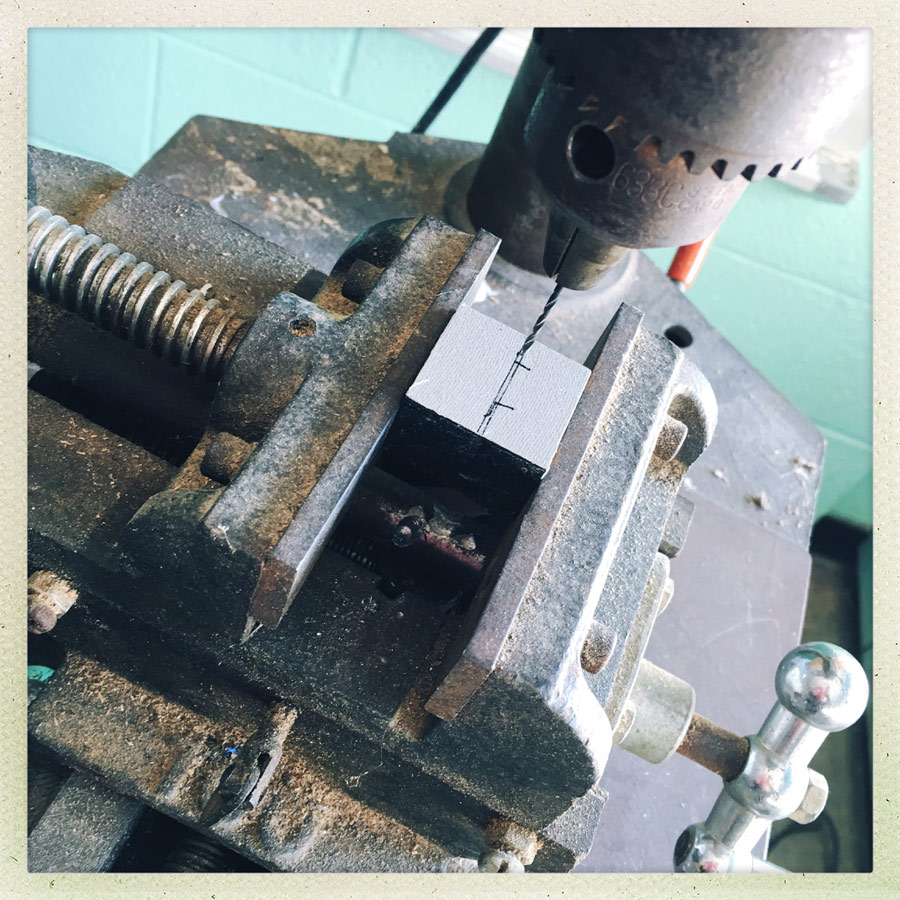

drilling the ebony

I use a piece of gaffer tape on the ebony, mark it, and drill a hole at either end. The vise is a machinist’s vice that allows precise adjustments. Often, I use precision tools like this, then just eyeball everything anyway. Mostly, it’s way better than holding the piece of wood between my shoes, hunching over, and drilling it with a hand drill like I did in high school.

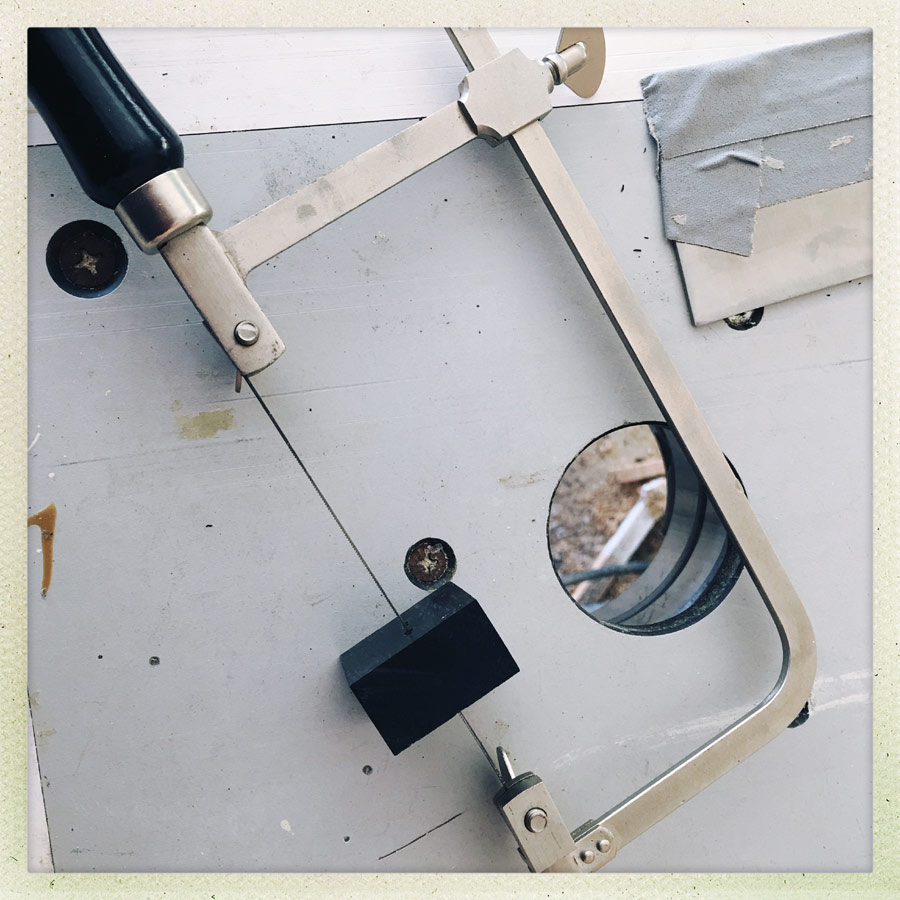

widening the cut with a jeweler’s saw

I used to use a broken coping-saw blade, thinned down with a file, before I discovered jewelers’ saws are pretty inexpensive. With a jeweler’s saw you can cut a slot that’s fine enough that it’s actually thinner than the blade that’s going to go through. Formerly I’d have drilled a line of holes and then sat there with a tiny bit of saw blade clamped into a vice-grip and worked at it for hours. With the right tools, so far everything I’ve shown has taken about 15 minutes including cutting the ebony and maple blocks (not shown).

opening the back of the ebony with a dremel tool

A dremel tool with a milling head replaces a small chisel and an hour’s work and some inevitable bleeding. I love the smell of burning ebony. I hog the back of the front block out, so there’s lots of room for all that wonderful epoxy to bind and make a great big strong support for the front of the knife.

fine fitting the blade

Then it’s time for about an hour of work with a hand-file – there’s no way around it. Ebony is hard and cakes up a file, but it’s the only way – I file a bit, test the blade for fit, file a bit, test the blade for fit, etc. One trick (not shown) is to have a bit of black grease (“inletter’s black” sold to gunsmiths) that you can wipe onto the metal piece, try to fit it, and then you can see where it’s binding by where the grease is wiped off. I use sharpie for the same purpose.

Next up, prepping the handle and finishing! [Click Here]

“Damascus” steel is a general class of processes in which a blade is made stronger by forging it out of layers of different compositions of steel. In the classical process practiced in Damascus (hence the name) the steel is “wootz” or dendritic steel – you smelt the materials in a forge so that the different compositions partially separate – the result is you have high carbon and lower carbon, separated by their different weight, with a sort of feathery transition zone between the compositions. That is then folded and welded a few times and produces a lovely watered pattern. The Japanese hit on the same process (probably not independently, it was used in India as well as the Middle East) and used to smelt their steel in a sort of conical crucible, then broke off the high carbon tip and forged layered blades of high/low carbon.

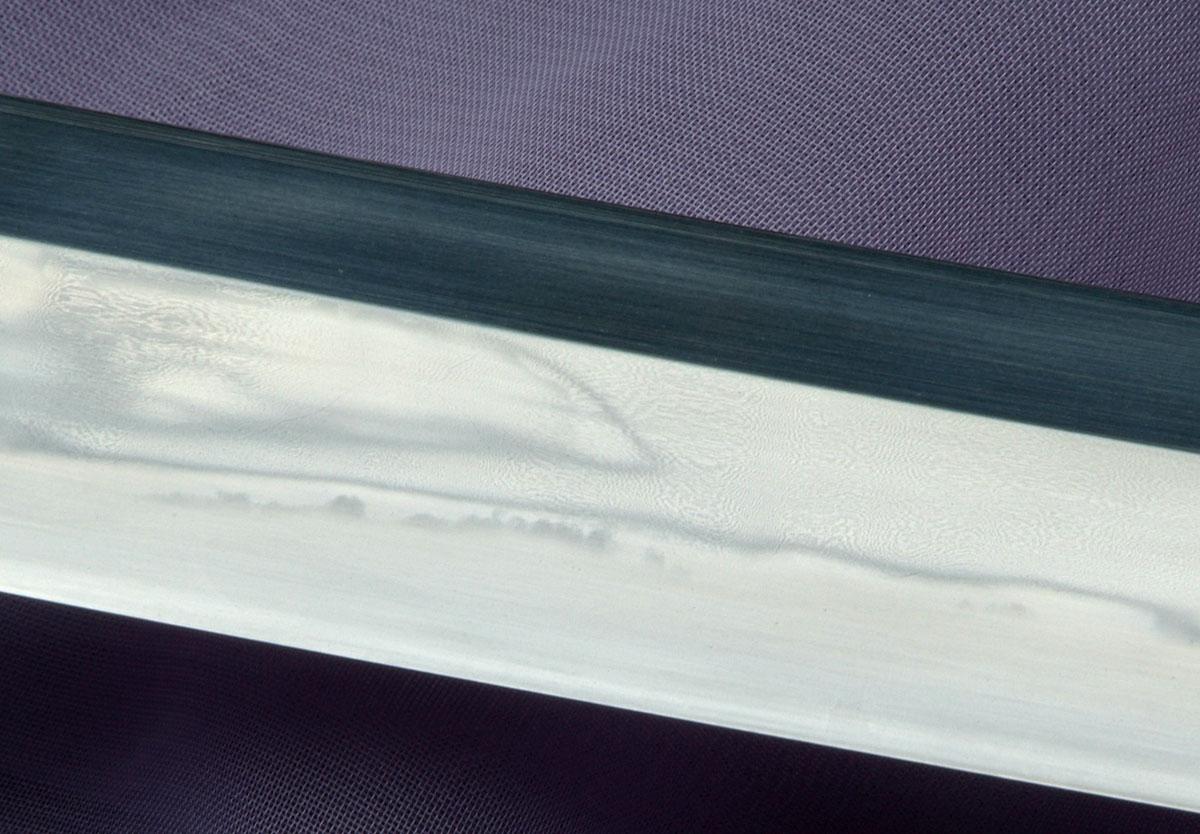

closeup of a modern-made katana (“wall of flame”, forged in 1997)

Japanese blades have a distinctive pattern along the edge, which results from differential quenching. In the blade above you can see both the fine pattern from the layered welds and the cloudy pattern of the quenched edge.

If you’re interested in damascus blades, the Pakistanis and Chinese are doing heroic work turning old military ships into swords for decadent reenactors. Take a look on ebay; the Paul Chen Forge (China) is doing great work as well. I find it somewhat bemusing that in 2016 you can buy a damascus layered viking sword that would make a viking eorl cry with joy, for about $200, on ebay. In the time when swords mattered, a sword like that would have been worth more than a king’s ransom. There were some novels (was it Marion Zimmer Bradley’s Mists of Avalon?) in which Excalibur was a layered-forged blade of meteoric iron; that would be a very rare and fine sword, indeed!

If you have the chance to visit the swords by Assad Ullah,[met][imp] which are probably par with some of the better Japanese works, there is one in the Met in New York, and a pair at the V&A in London. The V&A also has a very fine katana blade by Kunihisa,[va] which is worth a trip.

Napoleon and many of his commanders that participated in his Egyptian/Syrian adventure wore “Sabres A Mameluke” instead of the broad, heavy saber of a European hussar – shamshir, often priceless pieces looted from the ottomans. A lot of priceless Japanese swords wound up in yard sales in the US, after coming home in G.I.’s dufflebags during the war. Swords have always been lootables.

Gorgeous! Love that you use a jeweler’s saw. Those things are so incredibly useful. Can’t wait to see the finished product! This is going to be a beauty! I just love that pattern in the steel.

Here is a use for a Katana that doesn’t involve cutting anyone – making a Japanese chess board . Japanese craftsmanship is amazing.

Yes, Mists of Avalon does describe Excalibur as being forged of meteoric iron, and described as being “the price of a kingdom”. Those aspects of its description are about a third of the way through Chaper 18 of Book 1, for the interested.

That’s a nice piece of ebony. You don’t see it that naturally dark anymore. Not on guitar fingerboards, anyway.

kestrel@#1:

Jewelers saws are incredibly useful for many things!

jester700@#4:

Unfortunately, a lot of craft woods have become difficult to find. I’m really happy that my hoarding instinct kicked in – a 20lb block of ebony now is probably rare.