[Spoiler Warning: If you haven’t seen Seven Samurai, I am going to drop an important plot-point. And what’s wrong with you?]

I grew up reading about feats of derring-do, famous last stands, and martial arts philosophy. My favorite movie was, and remains, “Seven Samurai” by Akira Kurosawa – it’s an extended meditation on the different aspects of military honor, courage, despair, humor, and the fleeting moments of peace that warriors can occasionally snatch out of the mud and blood and awfulness.

Wisdom is: not picking a fight with someone who looks at you like that.

Once you’ve thoroughly absorbed an idea, then you can start to explore the contact-points where it bumps up against the rest of reality. When I was 14 I thought the duel scene between Kyuzo and the loud ronin* was cool because of the bravery of two men trying to fight face-to-face with 27-inch razor blades. Years later, I thought that Kyuzo should not have allowed himself to be manipulated into a fight; he should have been like Shimoda, the leader, who probably would have figured out a way to defuse the situation. Now, I see the whole incident as a parable of social mores and toxic masculinity; neither of them can back down because their society does not allow it – someone has to die.

The broader conflict is the samurai, who have agreed to defend a helpless village of peasants against a marauding band of brigands. The odds are horrible: 10 to 1 – the samurai know they have signed up for a hard affair, and more importantly, it’s not going to be glorious: no nobles or minstrels (except for the unseen eye of Kurosawa’s camera) are going to hear or sing of their deeds. Kurosawa reaches down into the core of what is military honor: doing something hard because someone’s got to.

People Sleep Peacefully in Their Beds at Night Only Because Rough Men Stand Ready to Do Violence on Their Behalf*

One piece of military honor is the idea that the conflict is worth it. That people aren’t risking their lives and taking others’ because some prince wants a bigger palace, or some defense contractor a bigger mansion. In Kurosawa’s neatly delimited situation, the value of the samurai’s actions is very clear. The “good war” ideal has been with humans for a very long time, indeed. Thomas Aquinas attempted to lay out the cases for “Just War” but I tend to reject his reasoning, because it’s entirely tilted toward the state: the state is given the monopoly on violence, and one cannot fight justly without being embedded in the power structure.*** Kurosawa’s samurai would have laughed at that; they had work to do. Yet states reach for Aquinas’ arguments when they need an excuse: we can credit Aquinas with giving the Bush Administration ammunition when they declared insurgents to be “unlawful combatants.”

“Weapons are unfortunate instruments. Heaven’s way hates them. Using them when there is no other choice – that is Heaven’s Way.” – Yagyu Munenori

In most parts of the world, we no longer live in the warring states feudalism of 16th-century Japan. And, per Aquinas, it’s mostly states that do war upon eachother. I believe we can no longer disconnect military honor from the motivations of the state. There are obvious cases, My Lai, the MSF hospital in Kandahar, Operation Rolling Thunder: dishonorable and inglorious massacres – over and over and over again. In a war like Vietnam, or Iraq or Afghanistan, there is no credible justification the government can offer. The soldiers, then, cannot honestly claim that they are fighting justly even though they are embedded in the power structure of the state. It’s worse, actually, since any soldier serving in a state’s military cannot credibly say they did not know in advance that governments tend to lie about the justifications for wars.

In most parts of the world, we no longer live in the warring states feudalism of 16th-century Japan. And, per Aquinas, it’s mostly states that do war upon eachother. I believe we can no longer disconnect military honor from the motivations of the state. There are obvious cases, My Lai, the MSF hospital in Kandahar, Operation Rolling Thunder: dishonorable and inglorious massacres – over and over and over again. In a war like Vietnam, or Iraq or Afghanistan, there is no credible justification the government can offer. The soldiers, then, cannot honestly claim that they are fighting justly even though they are embedded in the power structure of the state. It’s worse, actually, since any soldier serving in a state’s military cannot credibly say they did not know in advance that governments tend to lie about the justifications for wars.

No American soldier that flew air strikes in Libya can delude themselves that they were fighting a just war; for one thing, Aquinas’ idea that just wars are between states makes no sense if the premise for the war is that there is no state on the other side – it’s a “failed state”, i.e.: not a legitimate government. In Aquinas’ terms that means that a state is going to war against a bunch of civilians, with some “unlawful combatants” thrown in.

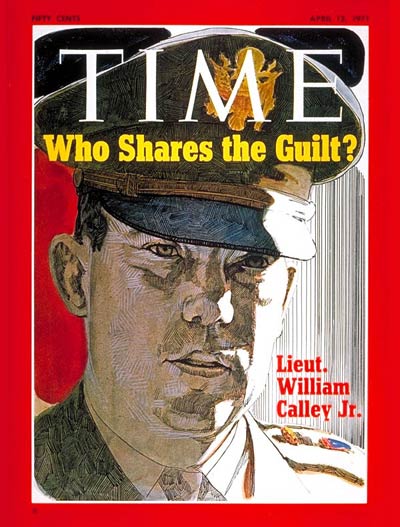

To answer Time Magazine’s rhetorical question on the cover: “everyone who participates.” Lieutnant Calley may have ordered the killings, but the supply train that gave him and his men weapons, the transport pool that delivered them to the village, the chain of command that trained them and placed Calley in the wrong place at the wrong time: they all share the guilt. So, too, does The President and The Secretary of Defense, MacNamara, who knew at the time of the Gulf of Tonkin Incident that it was “friendly fire” or a mistaken attribution.

The reason we admire the seven samurai is that they were fighting defensively, and justly: their foe was implacable and violence was going to happen no matter what. The reason we honor the seven samurai is because they fought at long odds – 10:1 – and knew that they were probably throwing their lives away. We admire Kyuzo for going sword-to-sword with the loud ronin because it was somewhat of an even match. In spite of the clear skill differential, Kyuzo was risking his life and so we at least accord him some respect for stepping up to that test.

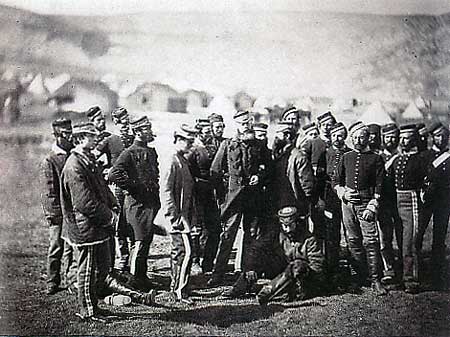

The survivors of the Light Brigade

Military honor starts to thin out when the force and skill differential gets too large. We probably would not honor Kyuzo if he fought a duel with a 12-year-old**** or a beginner. Historically, that’s why sword-masters would only teach, and would never duel: it was considered too unbalanced to be honorable. A beginner against a master was dishonorable slaughter. Yet, when nations engage in unbalanced war, the balance doesn’t seem to matter. Well, sometimes it does: there was outcry when Germany crushed “plucky little Belgium” in WWI. Generally, it’s the bravery of the respective foes that we’re honoring: The Charge Of The Light Brigade was an incredibly stupid blunder, transformed into military glory thanks to some propaganda poetry and the undeniable courage of the survivors of an insane charge into the teeth of emplaced artillery. Nobody wrote any poems about the Russian gunners who served their pieces and did vastly disproportional damage to the oncoming heroes.

This is why I get puzzled by how wars are reported today; I can’t tell to what degree it’s the propaganda of the victors, or the control of the media. Perhaps future military historians will write different assessments of the “great battles” of our time, like The Battle of 73 Easting, in which state of the art US tanks that hugely outclassed 1950s-era Iraqi armor conclusively obliterated their slower, blind, and under-armed foe.***** By the reasoning of military heroism we should be writing poems about the bravery of the Iraqi tank crews, some of whom probably had no idea what hit them. The equation of heroism has flipped upside down: we refer to US special forces as heroes for going in with night vision, state of the art gear, squad communications radios, and endless hours of practice against insurgents that are pretty much enthusiastic amateurs. We are expected to laud Chris Kyle, a sniper, who – thanks to excellent rifle and optics and plenty of training opportunities – was able to shoot people in the head from distances past where they could even see him. Kyuzo, he was not. Kyle is metaphoric for the American way of fighting wars: dropping high explosive on our foes from a safe distance, sniping someone from a safe distance, firing a hellfire missile from a drone while sitting in a chair at a safe distance.

It’s not a recent thing, I’m sad to say. In a posting I did about Smedley Butler, Pierce R. Butler commented that Smedley did win two Congressional Medals of Honor. I hadn’t mentioned that in my posting because, as you can see, I am on the fence about military honors. So, incidentally, was Smedley Butler. One of his CMH was from his involvement in the taking of Fort Riviere in Haiti.

On the seventeenth, according to efficiently executed plan, Campbell blew his whistle at 7:50 AM and advanced with his company in skirmish formation, Benet automatic rifles providing cover from the flanks. The fort had been surrounded by about 100 marines and sailors in three converging columns; every avenue of escape was closed. “Fire from the garrison,” as Butler described in his report, “was heavy but inaccurate, and we had no casualties.” The only entrance to the fort was a breach in the west wall large enough to admit only one man at a time. A sergeant, a private, and then Butler himself dashed into the breach, followed by the rest of the Fifth Marine Company. “A melee,” according to Butler’s report, “then ensued inside the fort for about ten minutes, the Cacos fighting desperately desperately with rifles, clubs, stones, etc. during which several jumped from the walls in an effort to escape, but were shot by the automatic guns.”

The entire battle lasted less than twenty minutes, fifty-one Haitians were killed, there were no prisoners, no survivors. Butler radioed Colonel Cole at 8:50AM that “no operation could have been more successfully carried out. Professional efficiency of the officers and splendid grit of the men.” Years later, he commented: “The futile efforts of the natives to oppose trained white soldiers impressed me as tragic. As soon as they had lost their heads, they picked up useless aboriginal weapons. If they had only realized the advantage of their position, they could have shot us like rats as we crawled, one by one, out of the drain.” The only American casualty was a man who lost two teeth when hit in the face with a rock. [1]

His earlier CMH, awarded during the Veracruz incident, did not involve the slaughter and machine-gunning of ill-armed and untrained natives. In fact, Butler didn’t really do any fighting at Veracruz, he was gathering intelligence and basically in a staff role. When he was awarded the medal, Butler wrote to his mother that the medal was for “Heroism, to have it thrown around broad cast is unutterably foul.” He said he could not stand to have his sons “proudly display this wretched medal, or rather wretchedly awarded.” He referred to the formal presentation in 1916 as a “farce” that made him “party to a vile perversion of our Sacred Decoration.” He was ordered to keep it. Source:[1]

At the Battle of Rorke’s Drift, we see 150 British redcoats fighting with rifles, rocks and sticks against a superior force – just like the Cacos at Fort Riviere – except they survived (largely because the Zulus backed off and left the field, possibly out of respect for valiant foes) There were more Victoria Crosses awarded for that fight than any other before or since. It doesn’t appear that military heroism always is on the side of the underdog; Butler’s trained and well-armed troops, with cover from automatic weapons, massacred a bunch of amateurs that they outnumbered and took by surprise.

There’s no “Just War” – there’s Just Us. -me

Iraqi forces besiege Mosul: where did that M-1 Abrams come from?

This topic is on my mind because of Pierce Butler’s comment, and because I’ve been watching for atrocity to occur at Mosul. As I mentioned earlier, the Iraqi military has fielded thermobaric multi-launch missile systems to – let me be blunt – flatten parts of Mosul before troops move in. Area bombardment weapons against a city; that’s bad. But it gets worse, the US is preparing to – again let me be blunt – massacre survivors attempting to escape:

The U.S.-led coalition has developed plans to target Islamic State militants from the air if they attempt to escape the Iraqi city of Mosul and head west toward Syria, as Iraqi ground forces close in on the city from several sides, a top U.S. general said Monday.

“This is all about getting after (the Islamic State) and setting up an opportunity where, should they try to escape, we have a built-in mechanism to kill them as they are departing,” said Lt. Gen. Jeffrey Harrigian, commander of U.S. air forces in the Middle East.

Blocking militants from escaping has been a key challenge as U.S.-backed Iraqi and Syrian ground forces have retaken towns and cities from the Islamic State. Hundreds of militants have managed to slip away. [Source]

“Hundreds of militants have managed to slip away.” It’s called retreating. It’s what you do when you lose a battle; especially when you’re vastly outgunned, surrounded, and your enemy has announced that they plan to kill you anyway.

America is expected to suck up to its military, and treat them as heroes. “Thank you for your service” fools mutter when they see someone in uniform. Killers like Chris Kyle or Smedley Butler are treated as if they are extraordinary paladins, instead of being merely better equipped and more ruthless. Yet, I have come to see them as cowards. The military honor should go to the farmer-turned-insurgent who takes a shot at an American patrol, knowing that he’s going to be subjected to prolonged aerial bombardment and overwhelming return fire whether he does any damage, or not. Courage is knowing that you’re going to be helplessly pinned down by an AC-130 gunship, which you cannot possibly hurt, yet you raise arms against the Americans, anyway. The cowards are in the B-52s, in the invulnerable high-tech tanks, fighting in the dark with night vision goggles and satellite intelligence. And, as cowards are wont, they wildly scatter more and more high explosive, just like they did in Vietnam before they finally resorted to chemical warfare – and still lost.

At the end of the battle for the peasant village, after it is all but won, Kyuzo is shot down in the mud – all his skill mooted by a clumsily wielded musket. Kurosawa doesn’t hammer on the point, but we all see this for the tragedy that it is especially because it’s the man most skilled with the sword whose skill ultimately doesn’t matter at all. Shimoda sums it up best when he manages to gasp out, “Again, we survived” to Schichiroji and, the next day, “Again, we are defeated.”

At the end of the battle for the peasant village, after it is all but won, Kyuzo is shot down in the mud – all his skill mooted by a clumsily wielded musket. Kurosawa doesn’t hammer on the point, but we all see this for the tragedy that it is especially because it’s the man most skilled with the sword whose skill ultimately doesn’t matter at all. Shimoda sums it up best when he manages to gasp out, “Again, we survived” to Schichiroji and, the next day, “Again, we are defeated.”

We honor the human drama of the great last stand or the fight against all odds, like the seven samurai defending the peasants even though they know it’s a crazy thing to do. We honor Jean D’Anjou and the demons of Camerone.

So when did we become the cowards?

[1] Hans Schmidt: “Maverick Marine. General Smedley D. Butler and the Contradictions of American Military History” The reader should consider the entire paragraph describing and quoting Butler’s reaction to his CMH as a paraphrase from Pages 72-73; I lightly re-arranged and omitted some of the text but the phrasing and vocabulary are not mine.

Thomas Aquinas: On War

Smedley Butler: “War is a Racket”

If you stick around and keep reading this blog, I eventually plan to post a story of military honor from one of my favorite books. It also involves intrepid leaders going through walls; though no medals are broadcast and the entire incident would be largely forgotten except for the memoirs of a real military hero.

(* For those of you who haven’t seen the movie: a sword expert is doing a demonstration with bamboo swords, and easily defeats his opponent. The opponent, however, doubles down and challenges Kyuzo to do it with live steel. Kyuzo tries to tell him it’s pointless and he’ll win again, but the loud samurai calls him a coward and draws his sword. At which point, Kyuzo uses exactly the same technique and timing, and kills him. Important notes in this scene: Kyuzo’s cut is a defensive riposte – the attacker leaves himself open as he launches his attack: Kurosawa is subtly pointing out that offensive movements almost always include a path to their own defeat. Kyuzo’s calmness and focused lack of bluster is why he can out-time the loud samurai. If the loud samurai had simply shut up and engaged in a better strategy, he would not have lost so easily.)

(** I thought it was George Orwell who said that, but it turns out that we’re not really sure.)

(*** Rousseau was accused of fomenting insurrection when he cut at the roots of the state’s right to monopolize war, arguing that a state that breaks the social contract has no legitimacy and therefore need not be treated with the respect – and the right to war – due a state)

(**** I loved the denouement of Valmont, with Danceny, who was so young and innocent-looking but knew sufficiently how to use a sword.)

(***** A friend of mine was there, commanding an M-1. He looked distraught when he told me that many of the Iraqi tanks were firing practice rounds, because Saddam Hussein was reluctant to give real war-shot to troops that might mount a coup against him. In terms of the disparity of forces at that battle, it wasn’t a battle, it was a slaughter. Mike Tyson versus PeeWee Herman, and PeeWee was blindfolded.)

The Battle of Algiers (1966) – some commentary on the courage of insurgents:

Re the **** comment – I found that really interesting, as that is exactly what happens in Yoshikawa Eiji’s novel “Musashi” – the eponymous hero cuts his way through fencing masters of a particular school, killing the 12 year old head of the family that challenged him. It is a part of Musashi’s education, but one for which he becomes reviled for later. His long time adversary, Sasaki Kojiro, makes a great deal of this and uses it to blacken Musashi’s name. Musashi however believes that he was given no choice and the child’s death was the inevitable result of the fencing school’s own manoevering.

I think one of the things that interests me about Musashi (the novel) is the exploration of what it means to be honourable, and the chief protagonists journey from brutal thug to aesthete swordmaster is neither pure nor simple, making many awful mistakes and misjudgements along the way.

After the repeated citations of my name, I really ought to say something meaningful – but right now all that comes to mind is the question of just what was attributed to Orwell but nobody knows?

For me, it’s a toss up between that and The Third Man. There’s another film worth a post or two.

They pitched the “honouring the valiant foe” angle in the movie Zulu (which I also have high regard for). I think it’s nonsense, and thought so when I first saw the film as a kid. Far more likely they just figured it wasn’t worth the bother.

Pierce R. Butler: This.

Rob Grigjanis @ # 4 – Thanks – I finally figured out that one shouldn’t do a search for “**” when the text doesn’t have it…

So when did we become the cowards?

1776.

Didn’t your history teachers drill upon you the cleverness of insurgents firing from behind trees and such while the dumb redcoats marched in straight lines?

Rob Grigjanis@#3:

They pitched the “honouring the valiant foe” angle in the movie Zulu (which I also have high regard for). I think it’s nonsense, and thought so when I first saw the film as a kid. Far more likely they just figured it wasn’t worth the bother.

I’m tempted to go by memory, but I owe you a responsibility to play it safe and bust a scroll of google…

Yeah, it’s as I remembered it: the Zulu force at Rorke’s Drift was one of the reserve troops from Isandlwhana and had been in the field for weeks and had wounded and were in poor supply. The wikipedia article says they hadn’t eaten in 6 days (which is -wow-for combat troops!) I agree with your assessment, “these guys are nuts! let ’em rot!” and they leave. Cetswayo wasn’t stupid, either, and knew that he had fought a pyrric victory at Isandlwhana and could easily have sent a runner to call back the troops at Rorke’s Drift to replenish ranks.

The point still remains: who were the military heroes, the British with modern rifles at Isandlwhana, or the Zulus, that took them with spears? Frankly, that battle was an ill-fought affair – particularly by the British pinhead-aristocrats-in-charge. I have always assumed that a lot of the gloriousness of Rorke’s Drift was “oooh look sniny thing!” to distract from the stupid defeat at Isandlwhana. Kind of like the Charge Of The Light Brigade – “ooooooh sure it was mismanaged military stupidity but it was gloriously mismanaged!”

The Third Man is incredible. I should do a “greatest movies” commentariat(tm) thread. Can Stanley Kubrick’s entire body of work count as 1, or do I have to choose?

Pierce R. Butler@#6:

Didn’t your history teachers drill upon you the cleverness of insurgents firing from behind trees and such while the dumb redcoats marched in straight lines?

Oh, yeah, silly me. I remember that!!! The same history teachers that drill the cleverness of insurgents placing IEDs in roadways, and Vietcong sappers sneaking into the wire at night.

usagichan@#1:

I think one of the things that interests me about Musashi (the novel) is the exploration of what it means to be honourable, and the chief protagonists journey from brutal thug to aesthete swordmaster is neither pure nor simple, making many awful mistakes and misjudgements along the way.

I haven’t read it since high school. It might be interesting to reread it with adult-turned-peacenik eyes.

The movie versions of the novel were so bad, I almost forgot the novel happened at all. Even with Mifune, they were bad. Besides, Tatsuya Nakadai would have been a better casting. Hmmm…. That’s predicated on my assumption that Musashi was insane not enlightened. When I read about him first, I didn’t have the words like “PTSD” and “Bipolar Disorder” but armchair psychologists (and real ones!) would have a field day with Musashi.

cuts his way through fencing masters of a particular school, killing the 12 year old head of the family that challenged him

It’s hard to sort the real incident from the novelization and dramatization of the incident. But it sounds like a horrible affair: some marketing genius in swordclan.com thinks “We can put about that our 12 year old head killed Musashi! Yeah! We’ll be swimming in ryo!” The story would have been better if Musashi had cut down most of the followers and given the kid a toy ball and a sandal-print on his hakama.

OK, now I just busted a scroll of Wikipedia about the incident and it’s pretty impressive. It sounds like the Yoshioka simply could not resist tickling the tiger. Wow! I don’t recall the movies going into the whole “Musashi versus Yoshioka School” in much depth – they should have. Lots of potential for action there.

Marcus @7:

Paths of Glory counts as two on its own.

I absolutely loved Seven Samurai. I have frequently thought about watching it again but what holds me back is the sense of deep sadness I felt when Kyuzo dies. It is a tribute to Kurosawa’s filmmaking that even though intellectually I know it is only a story and a fake cinematic death, yet the emotional impact was such that I cannot bear the thought of experiencing it again.

Mano @11: For me, the sadness is eased by the fact that these guys went in clear-eyed, knowing they would probably die.

A film I will almost certainly never watch again is Testament. A brilliant, deeply moving film about a family in the aftermath of a nuclear war. I get choked up thinking about it years after watching it. That Jane Alexander didn’t win the Oscar was further confirmation that the whole thing is a joke.

Rob @#12,

Totally agree with you about Testament.

Mano Singham@#11:

I know what you mean, but I still make a pilgrimage to that movie every couple years.

Some context: Kurosawa was doing a lot of work with the character of Kyuzo. Kyuzo’s costume is very old school bushi, and he’s older than the others. The movie is set in the mid 1580s – a decade after the battle of Nagashino, which Kurosawa returned to in “Kagemusha.” Nagashino was notable in the way that the Shingen forces were gunned down by Nobunaga’s musketeers, in a most un-sporting manner. Many of the samurai at the time felt that Nagashino and the ascendancy of Tokugawa Ieyasu meant the end of samurai culture. Oda Nobunaga was assassinated in 1582 – a couple years before the time the movie was set. This is all relevant, why: there were a lot of ronin running around Japan at that time, because of the turmoil and losses from the unification war that began with the destruction of the Takeda at Nagashino; samurai culture was at a cross-roads: the old school saw their lives slipping away from them and many of them were dispossessed and threadbare.

I believe we are expected to assume a few things: that Shimoda and Shichiroji were probably on the losing side at Nagashino (i.e.: the Takeda) In one of their conversations they reference Shichiroji laying low in the ditch to escape; and a piece of castle falling down – that’s probably an oblique reference to the seige of Noda castle (1573) where Takeda Shingen was killed, and which led to Takeda Katsuyori’s unwise engagement at Nagashino. I believe we are also supposed to assume that Kyuzo was one of the old school bushi who had survived those engagements, and Kurosawa expects the audience to fill in the pieces and see Kyuzo as a left-over of a dead period. Each in their own way, the older samurai are coping with the end of samurai culture as Japan was heading into unification under Tokugawa. Gorobei* is also clearly very experienced. Kurosawa deliberately leaves the background of the samurai vague, so we don’t really know (or care) who held their individual allegiance during the Takeda war – part of the beauty of the movie is that they clearly don’t care and neither do we. To contextualize this for Americans, it’d be as if, 10 years after the US civil war, a bunch of confederate soldiers and some union soldiers of mixed ranks, along with a wide mix of social classes, came together as if none of the civil war had happened at all.

With respect to class, Katsuhiro is clearly an upper class young sprig; his clothes are nicer and he’s well-mannered. And, of course Kikuchiyo is a peasant, carrying a sword and a brevet of nobility for a thirteen-year-old. (He also handles his sword with a casualness no noble ever would) Kurosawa is playing the same levelling game, here: class is irrelevant, the seven have more important things to worry about.

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition;

and all that.

The problem with not watching the movie because of Kyuzo’s death is you miss the wonderful scene when Shimoda meets Gorobei and Gorobei says “To tell the truth, I’ll join you because I’m fascinated by your character.” Or the moment when Shimoda is trying to recruit Shichiroji, who says “yes” before he even gets a chance to tell him what the mission is. And one of the most beautiful bits of footage in any movie, when Shimoda breaks out his bow and starts firing arrows in the driving rain, as if he’s in some state of grace, and the water snapping off the string leaves vees in the air.

(*Damn it, can we talk about Gorobei? One of the coolest supporting characters in any movie, ever, and played with such understated grace. The characters are so vivid you feel like you know them.)

PS – the score to seven samurai is also notably excellent. It’s one of the best movie scores ever done.

It blends so well into the movie that you need to listen to it in isolation to realize how awesome it is. It’s up there with Vangelis’ score for Blade Runner and (of course) Williams’ score for Star Wars.

When isn’t foreign and military policy based on cowardice and hypocrisy? War is like any form of violence, from single people to millions. Unless a person or country is defending against an unprovoked attack, the person or country is the aggressor. And almost certainly, a bully.

Nearly every country’s war tactics involve attacking only those who can’t fight back or intimiditing and coercing countries with the threat of war. (As the saying goes, terrorism is how the poor wage war, and war is how the rich wage terrorism.) Long gone are the days of “honourable warfare” where armies faced off against an equal opponent and were willing to risk losing.

The rule of war nowadays is:

a) If you have overwhelming force, attack and annihilate. The goal is exerting and demonstrating power.

b) If you don’t have overwhelming force and might lose, look for a stalement or “detente” until you have overwhelming force. Then you attack and annihilate.

You ask at the top the same question Time asked, “Who Shares The Guilt?”, and you said “everyone involved.” Usually, you go a lot further than I do, but I’ll state an opinion I stand by that you haven’t said: Anyone who participates in a war is a war criminal.

Rob Grigjanis:

Apropos nothing, Kubrick was 29 when he made “Paths of Glory.” Kurosawa was 44 when he did “Seven Samurai.”

I’m not sure if there’s a category for “youngest director to make a masterpiece” but that’s just because Kubrick’s “The Killing” and “Paths of Glory” put him on that category, twice.

Intransitive@#16:

Anyone who participates in a war is a war criminal.

I have been leading the discussion in that direction; I agree with you completely.

There are even problems with waging purely defensive wars; offensive wars being completely off the table. Eventually I intend to summarize some of Cecile Fabre’s arguments in that vein – they’re forehead-slappingly good.

(To spoiler myself a bit, I planned to argue first that the argument that “it’s OK to defend yourself” is frequently abused in warfare. From there, springboard to Fabre’s arguments, which go a lot farther than I got on my own.)

The thing about concepts of honour and heroism is that they are all too frequently archaic hangovers from past societies that thought very differently to how we do. In many ways this has always been the case – honour and heroism have always been glorious and slightly archaic virtues, suited to a grander, less complicated time. The central tension in almost all heroic literature is the struggle of the hero to balance his commitment to the outmoded “heroic” lifestyle that gives his existence meaning with his responsibilities to wider society as it now is. We find it in the Iliad, with Achilles’ heroic temper at a personal slight putting his comrades in peril and Agamemon’s obssession with appropriate distribution of prizes causing strife and discord among the ranks. We find it even more strongly in the Odyssey, where Odysseus is confronted with Achilles’ shade in the underworld, remarking that his life of hollow bloodshed was simply not worth it now he has died and lost for good. Odysseus, by contrast, longs not for a glorious death in battle but for a long and prosperous life with his family at home, a metaphor for a Greek world leaving behind warrior-aristocratic feuding and bloodshed and embracing the political life of city-states. Beowulf has similar themes 1500 years later – the heroic monster-slayer is not who the world needs, the just king who can look after his people is. Both epics still vaunt decidedly anti-social heroic behaviour though – raiding, piracy and pillage are still seen as glorious acts if you come through them alive and enriched. This is still a fractured world where internecine violence is simply a fact of life. The sort of world, in fact, where it is still possible to be a classic warrior hero, but where being one is far from uncomplicated. In truth it was never uncomplicated.

The climax of the Odyssey is also an against-the-odds battle to the death – with Odysseus, his son and the two loyal herdsmen taking on all 108 suitors in the great hall. But it is a very strange scene indeed to modern eyes, given that Odysseus is the aggressor in a tale of revenge and the divine protection his party enjoys means the result is never in serious doubt. There is also some seriously unpleasant mutilation of the disloyal household servants. The emotional theme seems to be one of justice restored and slights against honour made good. It is not a close model for modern consideration.

Vergil’s Aeneid is rather different. In typical Roman style he tries to recast the largely personal, reputation-based honour of Homeric heroes in terms of duty to family and state, and makes overcoming the desire to do traditionally heroic but damaging things itself a heroic act. Where Hector wants to die in the front line, showing no fear even though he knows Troy is doomed, Aeneas sees the nobler course in escaping and saving his family and his household gods from destruction. Vergil seems to explicitly understand the tension of maintaining heroic pretensions with being a useful member of society – a traditional Homeric hero is who we want to be, deep down, but most of the time we shouldn’t be and can’t be. The Aeneid was written during the great Augustan revolution of course, following the civil wars – a time in which Romans were keenly aware of how damaging personal glory could be and needed a strong ethic of loyalty to state and society. The Roman military ethos was very much an ethos of proper order and following proper orders – their concept of leadership and rank, imperium, deriving from the verb imperare – to order or command. The reckless maverick who operates outside the established order was not a character dear to Roman hearts. Some of this too is apparent in modern military ideals.

Aquinas, of course, had the military establishment of his own day to consider in his philosophy. People often think that medieval philosophers, especially those in religious orders, were entirely detached from the world, but this is simply not true. Aquinas’s writings on war follow in a tradition of scholastic thought that aimed to reconcile Christian notions of virtue and sin with the warrior-aristocratic culture of the knightly classes. Being a knight was essentially being professionally engaged in breaking commandments, but they were also wealthy, connected and powerful and the established church did not generally wish to antagonise them (most monks and churchmen had brothers and cousins who were knights – they were not a class apart by birth. Aquinas was of knightly rank himself). So elaborate philosophical justifications had to be constructed to square the circle, and money paid by military men to the church for salvational masses didn’t hurt either. By Aquinas’s day the crusading culture of the central Middle Ages was a century and a half old, and the sanctified military of the Templars was an accepted part of European life. That he found ways to justify war for himself and his audience is entirely unsurprising.

Intransitive@#16:

I’ve updated my OP with a video clip that pretty much says it all.

Marcus @9

Yep, the film version of Musashi you refered to was pretty poor (although not as awful as the NHK Taiga Drama version – a mess of miscasting and awful acting, over 45 hours or so…), but it is hard to dramatise such a vivid novel. I wish I could read the original Japanese, but while my conversational Japanese is reasonable, my reading level is about third grade, so it is somewhat beyond me.

The battle with the Yoshioka school is one of the highlights of the book from the point of view of pure action, and while a literary device it explains the genesis of the two sword style mentioned by the real Musashi in Go rin no sho (although I like episodes like the discarded peony cut by Yagyu Sekishusai – the perceptiveness and aesthetic that Yoshikawa ascribes to Musashi is a counterpoint to the violence to which his life was dedicated – the sword stroke as a work of art in itself).

My favourite samurai movie has to be Tasogare no Seibei (Twilight Samurai), although it may be that it was the first one that I could watch without subtitles so the pleasure was enhanced by the achievement (I missed some of the dialogue, but understood enough to follow the plot well enough). Still, Seibei represents an ideal of honour and duty, and the weight of those that the more action oriented Samurai movies don’t capture for me.

usagichan@#22:

My favourite samurai movie has to be Tasogare no Seibei (Twilight Samurai),

That’s a wonderful movie.

I jumped from “Seven Samurai” to “Harakiri” and “Sword of Doom” – I’m a huge fan of Tatsuya Nakadai (if you ever get a chance to see “Goyokin” on a big screen, do)

“When the last sword is drawn” is also amazing but oh so depressing.