This is a good explanation of how economic unfairness is perpetuated. From Robert Paul Wolff, “Autobiography Of An Ex-White Man”

I am going to trace the asset accumulations of two lower-middle class American families over a thirty-year period. The first family is Joe and Mary Smith, who are White, and their two children Skip and Jane. The second family is William and Esther Robinson, who are Black and their two children, Michael and Carolyn.

In 1950 after World War II, the Smiths buy a small house in a new suburban community, aided by an FHA insured mortgage. They pay $10,500, and secure a thirty year 6% fixed rate loan for $10,000, the remainder scraped together from money Joe has saved in the army. William Robinson also saved $500 from his army pay but he is denied a loan under the Federal Government’s explicit and official policies of racial discrimination. Unable to buy a home, the Robinsons rent an apartment for their family, at an initial rental of $120 a month.

Both Joe Smith and Bill Robinson find jobs in post-World War II America, and they make, let us suppose, exactly the same wage. What is more, let us imagine that over the next thirty years they get identical raises, and are never out of work. Now let us trace over a thirty-year period the housing expenditures and asset formation of the Smith family and the Robinson family. I am going to make some reasonable simplifying assumptions about changes in rental rates, insurance rates, and real estate taxes, and also about the saving propensities of families with disposable income. Let us see what happens to the Smiths and the Robinsons. Remember – the families have identical starting assets, they are the same age, they have equivalent jobs, they get the same raises, and – I shall assume – have identically stable homes with identically responsible and committed bread-winners.

The Smiths first. The annual cost of a 6 fixed-rate 30 year mortgage is $72/1000 or $720/year. Since this is a fixed-rate mortgage, that almost never changes over the entire 30-year period of the loan, despite the fact that between 1950 and 1980 the consumer price index rose by 341%. [The CPI for housing actually rose more than that, but let us keep this simple.]

In the thirty-year period from 1950 through 1979, Joe and Mary Smith pay out a total of $21,600 in monthly mortgage payments. They also pay insurance and real estate taxes, of course. I will assume that taxes and insurance start at $260 a year and rise slowly up to $1300 a year by the time the mortgage is paid off at the start of 1980. Suppose these items, over thirty years, total $22,550.

So, in thirty years, the Smiths spend $44,150 on housing.

But much of that is tax deductible, thanks to federal policies designed to encourage home ownership. For example, $11,600 of the mortgage payments is interest [the total paid out less the original loan]. In addition, roughly $17,500 of the taxes plus insurance is deductible real estate taxes.

So, over the years the Smiths have enjoyed a $29,100 tax deduction, which, we will assume, at an average marginal rate of 25% returns to them $7,275. Thus the net costs to the Smiths of housing has been $36,875.

The Smiths put $2,000 of this tax break in the bank, and spend the rest on such things as college educations for their children, Skip and Jane.

In 1980 the Smiths have a bank account of $2,400 [including bank interest] and a home which they own free and clear. In the intervening two years, real estate has soared, and their little house, even though thirty years old, is now worth $50,000 on the housing market. So the total assets of the Smiths total up to $52,400.

Meanwhile, the Robinsons have been living in their apartment and paying rents that rise steadily, thanks to inflation. I 1950 they pay $120 a month for their apartment, but over thirty years the rent rises to $350. [This is, of course, a very modest assumption. Real rents have risen considerably more.] Assuming a schedule of gradual rises, we can estimate that at the end of thirty years the Robinsons have paid a total of $82,200 for housing. This is $43,325 more than the Smiths paid, even though the Smiths were paying off the mortgage on their home, and the Robinsons were renting an apartment.

What assets have the Robinsons accumulated in thirty years? The simple answer is none. They have had no tax breaks from their rental payments nor do they own the apartment in which they have lived for thirty years, and because of the rising rents, they have been unable to save a portion of the Robinson’s salary.

Thus, purely as a consequence of discriminatory policies adopted explicitly by the Federal Government in the 1930s, the Smiths, who are White, have net assets of $52,400 in 1980 and the Robinsons, who are Black, have net assets of zero.

The long-term effects of the original discrimination do not end here, however. They are transmitted to the next generation – to Skip and Jane and Michael and Carolyn [all of whom, note, have grown up in stable, secure lower-middle-class homes with two parents and good family values].

First of all, the Smiths have been able to divert a considerable portion of their income to the education of their children, because of the beneficial laws and policies governing housing. This advantage shows up in the higher incomes the Smith children are able to earn, as compared with the equally talented but less-well-educated Robinson children.

Secondly the Smiths are in a position to make available to their children the advantages of home ownership. By 1980, when Skip is thirty-two, housing has risen so much that a new small house costs $100,000, not $10,000. Skip needs a $10,000 down payment to secure a mortgage loan, and even though he has a good job – better than his father was ever able to obtain – he simply cannot save the $10,000 out of his paycheck. But his father can now help him out. Refinancing the family home, which the Smiths now own outright, Joe Smith takes out a $10,000 mortgage and gives his son [tax free] the downpayment. In effect, the Smiths are advancing a portion of the childrens’ inheritence to them in this form. Skip buys a home and begins to enjoy all the advantages that his parents were able to secure thirty years earlier.

Michael, on the other hand, even though he has as good a job as Skip, will never be able to buy his own home, for his father has no assets that may be deployed to give him the down payment. The disadvantages of the fathers are visited upon the sons. Thoughtless social commentators will wonder why Skip is doing so much better by the year 2000 than Michael is, and will come up with elaborate cultural and psychological explanations, blaming low self-esteem [if they are liberals] or the lack of a suitable work ethic [if they are conservatives] but all of their fancy explanations will be wrong. The real explanation of the generations-long effects of explicitly discriminatory policies of previous eras , which continue to manifest themselves in dramatic inequalities of wealth, even after inequalities in income have been corrected by the marketplace or even by affirmative action and anti-discrimination laws.

I grew up in Baltimore and my life experience pretty much exactly mirrored Skip Smith’s – Wolff even nailed the price of my first house and the amount my dad gave me for the downpayment. If there are any typos in my copying, above, it’s because it’s hard to type when you’re cringing.

Wolff is not even heaping it on as it deserves to be heaped on. The inequality he identifies in 1930 is specifically that the newly-formed Federal Housing Authority relied on “redlining” – an implicitly racist loan-granting process, which was also used to segregate neighborhoods. In the city where I grew up, Baltimore, and bought my first house, redlining was embedded in housing sales – I remember when Thenwife and I went looking for a home, we were subtly directed away from the neighborhood where we finally settled down. Some of it is explicit “It’ll be harder for you to get a loan because they will not accept the property’s value” and some of it is implicit “This is a nice quiet neighborhood” may be racially coded. That was 1986 or thereabouts.

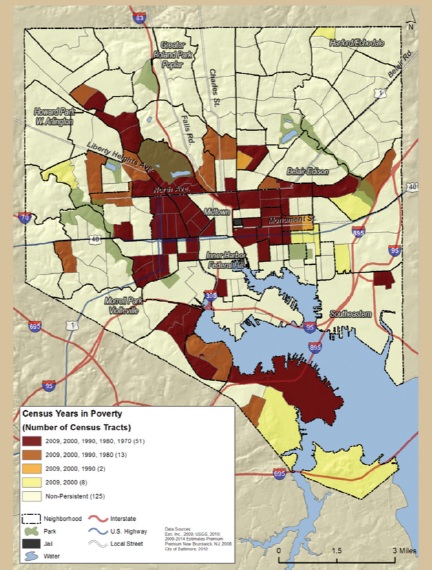

The map on the right illustrates years below the poverty line, on average; which happens to correspond exactly to which neighborhoods were redlined.

Baltimore Map, Persistent Poverty areas

I grew up in one of the white-colored regions on the map, at about the 11:00 position, and our first house was in one of the deep red zones at the 2:00 position near the center of the map, near old Memorial Stadium. When Baltimore was one of the shootier places in the US, in the late 1980s, I’d sometimes hear gunshots; my parents never did. Mondawmin Mall, where the Freddie Gray “riots” happened, BTW, is in the orange zone at the 9:30 position surrounded by red zones at the top and bottom.

Baltimore exacerbated its problems in the late 80s/early 90s with urban homesteading programs: the idea being that you could buy a down-at-the-heels old brownstone and – if you guaranteed to fix it up and live in it for a certain number of years – you got tax breaks and pretty much were given the property. So, what happened? Those that could afford to, did, then turned the places into rental properties. Meanwhile, they had tax breaks, yet demanded expensive city services like better policing and better roads – in some cases walls to keep undesirables out. So Baltimore further gutted its tax-base in order to hand out freebies to its wealthy. Mayor William Donald Schaeffer pioneered the idea of giving “useless” (read: near poor people) properties to developers, so you got glitz-pits like the Inner Harbor project which made a jillion dollars for The Rouse Corporation, who used the money to invent the mega-mall for the middle class who had fled the city. Rouse was one of those great “vertically integrated businesses” which not only deal-brokered developments, architected them, and had its own construction company that seemed to always win the bidding on their projects. I remember going to The Mall In Columbia (the first indoor mega-mall) in 1972, and it was so clean and everyone was so white. The developments (also Rouse Corp!) surrounding the mall, you got it: so clean and so white.

Wolff’s discussion hides how easy it is to fall off the “power curve” and drop from the ‘accumulating wealth’ into ‘paycheck to table’ existence like the Robinsons. It doesn’t take much: a bad investment, a corporate downsizing, an accident with high medical bills, a drug bust, and the machinery of society will grind you into mincemeat. One of the points that Wolff, who is a long-time Marxist, does not hammer on is that the Smiths are worth $36,000 to the capitalists, whereas the Robinsons are worth $82,000. The parasitic predatory lending practices that resulted in the housing and banking bust were not just ripping people off, they were creating a new class of people stuck in the Robinsons’ situation.

Keep this stuff in mind when you encounter, as Wolff calls them, “thoughtless social commentators” (or: “libertarians”) who are under the impression that they pulled themselves up from their own bootstraps and made something out of themselves. We are all “self-made” to the extent that we do anything at all, but none of us can ignore our starting conditions.

A few of my close friends would likewise be classified as Smiths, with parents that fronted the down payment for their house (after their expensive, straight marriages) which qualified them to start a mortgage. In the end, my living expenses are near identical to theirs–but my rent simply vanishes in a puff of smoke, whereas their mortgage payments are stuffing money in the walls. Unless something is done with this ridiculous housing market, a couple decades from now my friends will be able to sell their properties at a ridiculous profit, whereas I’ll be lucky to have finished paying my student loan. I jokingly call them class traitors but that would imply we were ever the same class to begin with.

Now imagine all the loops and traps that keep lower middle class folks in the lower middle class, and add in things like mental illness, PTSD, disabilities, addictions, un- or -underemployment, and domestic violence. Tada–the poverty cocktail. The amount of resources it takes to break this cycle is absurd. But to the sheltered, that’s all it is: A bill, an expense, a line of red in their budget. I don’t think they realize how bad it gets when it’s left to fester.

And people wonder why I get uppity when there’s murmurings of austerity from our government.

Shiv@#1:

Unless something is done with this ridiculous housing market, a couple decades from now my friends will be able to sell their properties at a ridiculous profit, whereas I’ll be lucky to have finished paying my student loan.

The student loan crisis is a very real problem. Basically, what’s happened is that capitalists have realized that if they can get you into debt at the factory store with a student loan, and put you in factory housing rental properties, they own your entire economic output for your entire life.

The obvious answer, which will come in time, is to kill the motherfuckers. Because short of that, nothing is going to work.

Now imagine all the loops and traps that keep lower middle class folks in the lower middle class, and add in things like mental illness, PTSD, disabilities, addictions, un- or -underemployment, and domestic violence. Tada–the poverty cocktail.

Yep. And there’s good arguments that the single best thing you can for the poor is give them money and let them sort out their problems. All that crap about the poor not being able to handle money – as Wolff shows us – it’s crap.

The jaws of the trap are snapping shut. I’ve been being a bit depressing in my last few posts so I will probably not go into that for a while.

PS – wrt to class traitors, one of the great back-handed put-downs of all time was Chou En-Lai to Kruschev: “we have something in common, we are both traitors to our class” (Chou being old nobility, having become a revolutionary)

How about reverse mortgages? Looks like a scheme in which the banks end up owning all the housing, to me.

Robert,+not+Bob@#4:

How about reverse mortgages? Looks like a scheme in which the banks end up owning all the housing, to me.

It does. Certainly reverse mortgages give the capitalists a chance to pick their choice of properties and own them at a discounted price.

If anyone wants to see what the end-game for this looks like, it looks like Singapore: very few people own property and most live in apartments. Which means that the speculators that build apartment buildings have an infinite supply of money and can always afford to buy more land, which drives up the price and puts private citizens out of land ownership and into rental.

http://smartpropertybuyer.blogspot.com/2008/02/major-events-that-impact-singapore.html

They want everyone to have nothing, but the opportunity to work – at the wage they set, which will be just above subsistence.

I’ve read and said similar things (here and elsewhere) about housing in the US, the predatory and prejudiced system started in the 1950s. The right wing and white only ever have two responses to reality and facts:

1) “That’s not true.” / “Prove it.”

2) “How is this my problem?”

It would be nice if there were simple solutions to housing (e.g. tiny homes, communal property purchase and living, building homes on water). But given how local, regional and federal governments pander to banks and the housing industry, nothing short of total system collapse will change anything. And the way things are heading, that’s inevitable.

We just bought a house. Nonno, we’re doing it all ourselves, our parents gave us nothing! Ecxept in my case support through college and always enough for all those educating fun activities.

And all that white and male “good home” privilege my husband got*.

And of course our talks with the bank were all pleasant. We’re not called “Yilmaz” after all.

*My in laws are the typical German traditional working class where the social net kept them from sliding down and where respectability politics opened them doors. But you notice the effect of “too poor to paint, too proud to whitewash on my husband.

Giliell, professional cynic -Ilk@#7:

One of the things I really like about Wolff’s explanation is that he shows how – all other things being equal – a single crucial decision can make the difference between a family on the up, and a family on the out. And it’s not even their decision.

We focus on things we can do (some) things about such as educational opportunity, but these traps are everywhere. And that’s without even getting into things like preferential taxation on wealth for the convenience of the investor class.