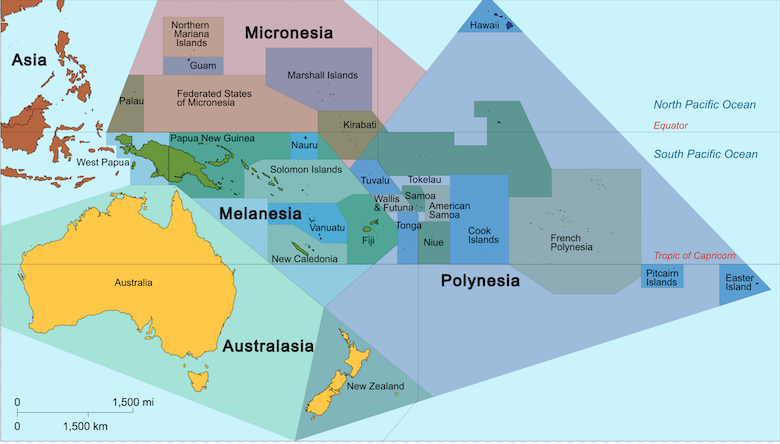

The Pacific Ocean covers almost half the surface of the Earth and despite its name can be the scene of massive storms. The entire region can be split into three regions, Micronesia and Melanesia that are on the western end of the ocean, close to Australasia, and Polynesia that occupies the central region. Polynesia is vast as can be seen by the size of the so-called Polynesian triangle consisting of Hawaii as the northern vertex, Rapa Nui (formerly called Easter Island) as the southeast vertex, and New Zealand as the southwest vertex. Each side of this triangle is about 9,000 miles. The people of Polynesia, despite being so widely dispersed, form a single, identifiable cultural group.