When it comes to research in experimental physics in areas that already exist, the frontiers that are usually explored are those of precision and size.

In the case of the precision frontier, the idea is to measure something more precisely than it has been done before because with greater precision there is a better chance of finding disagreement with theoretical expectations. Such disagreements (or ‘anomalies’), especially if they persist and are recognized as not being due to some errors in experiment or theoretical calculations, are the basis for thinking that there might be something new going on and may lay the foundations for some kind of breakthrough.

The other frontier is to extend the range of the parameters and in the case of high-energy physics, that means going to higher and higher energies. But this is enormously expensive. The Large Hadron Collider that was built at CERN at a cost of billions of dollars reached the existing energy limit and it resulted in the detection of the long-sought Higgs boson.

I had thought that there would be no political will to think of spending even greater amounts to build an even bigger accelerator but it appears that one is indeed being proposed.

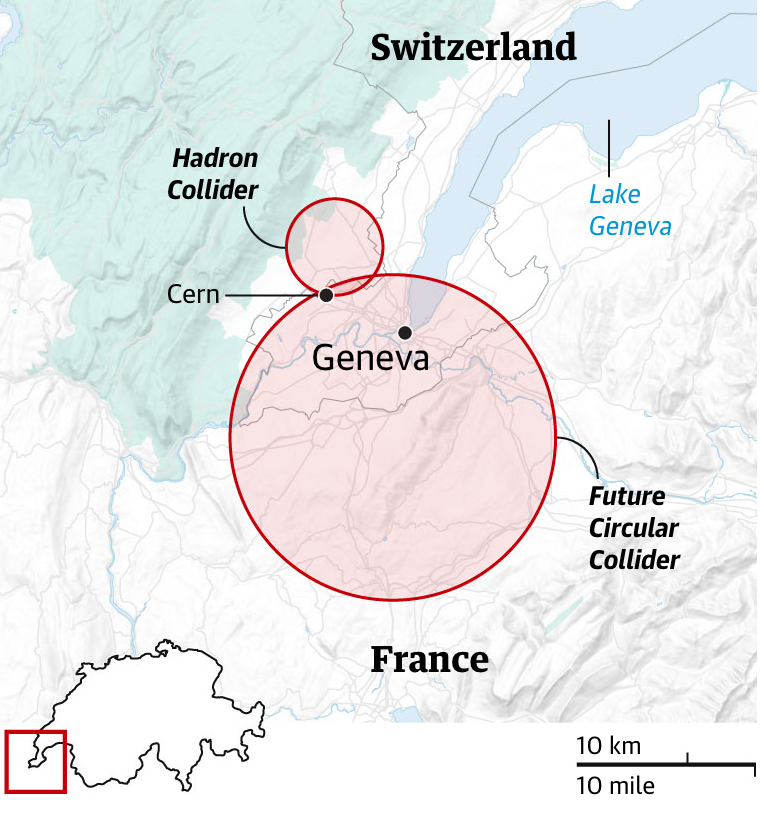

The LHC reaches the end of its life around 2041 and Cern’s member states must decide what comes next. The frontrunner is a colossal machine called the Future Circular Collider or FCC.

According to Cern’s feasibility report, the FCC would be more than three times the size of the LHC, calling for a new 91km circular tunnel to be bored up to 400 metres underground. The machine would be built in two stages. The first, starting in the late 2040s, would collide electrons into positrons, their anti-matter partners. At some point in the 2070s, that machine would be ripped out to make way for a new collider that smashes protons at seven times the energy of the LHC. The first phase will cost an estimated 15bn Swiss francs or £14bn.

The engineering alone is ambitious, but the FCC faces wider challenges. Cern’s member states, who will vote on the project in 2028, cannot foot the whole bill, so other contributors are needed. Meanwhile, a debate is rumbling on over whether it is the best machine for making new discoveries. It is not guaranteed to answer any big questions in physics: what is the dark matter that clumps around galaxies; what is the dark energy that pushes the universe apart; why is gravity so weak; and why did matter win out over antimatter when the universe formed? With no clear prize to aim for, [the director general of CERN Mark Thompson’s] job will be harder.

When the LHC was first proposed, the size of it was astonishing. The sheer size of the new FCC machine is staggering.

This is going to be very controversial. It is likely to face opposition not just from budget-conscious politicians but also from within the science and even the physics communities. This is because all those scientists who do not work in this particular area will fear that any money allocated for this will result in squeezing the budgets of every other area of science research. This debate was very heated even during the planning of the LHC. In these days, when science budgets are being severely cut in the US, the potential for tension and conflicts within science is going to be even greater.

A very expensive shot in the dark.

For some perspective on relevant energy scales:

The collision energies at FCC would be about 100 TeV. The Planck energy is about 1e16 TeV, and a (possible) Grand Unification* energy would be about 1e13 TeV.

Sure, there may be new particles “just around the corner”, but I wouldn’t bet on it.

* Unifying the electromagnetic, weak and strong forces.

I don’t remember what level of energies are involved (and couldn’t find it with a quick search), but apparently the size scale of a particle collider needed to detect whether the hypothetical graviton exists with current technology is approximately 3 light years. Which, as you may note, is quite a bit larger than 91 km. I’m not aware of any other hypothetical particles which we know what their likely properties would be if they existed.

“Current technology” suggests that maybe we should first see if we can improve the tech in order to get a lot more than 100 Teravolts out of a 91km or similarly-scaled* collider, just to increase the odds of finding useful, and if we don’t, provide more definitive evidence that there’s probably nothing else to find at any scale we could realistically create? Don’t know the state of cutting-edge physics and engineering well enough to say how much sense that makes, so just spitballing.

*I’m aware the 91km length was probably chosen specifically to get the nice round number of 100 TeV.

Meanwhile, the 5 big hyperscalers are planning on spending something like $600 billion on constructing AI datacenters in just the next 12 months…

@2

If I may translate for our red-blooded American readers:

The FCC (not to be confused with the FCC) will be the length of 995 football fields stacked end-to-end. America would be able to fit 123,151 football fields inside of that, which is about 0.09% the size of Texas (that’s a lot of football!). Unfortunately, all those football games are being played 437 yards underground, which presents insurmountable sportsball-related difficulties. Theoretically this project can attain per-particle kinetic energies that are still several orders of magnitude short of the kinetic energy of a thrown football (1 to 7.8 million), so it won’t be scoring any three-point field goals from home plate any time soon. This project is estimated to cost $19,000,000,000, or a little over seven days of average Pentagon expenditures.

Beholder @ 5

I was shocked to realise that the final estimate (about Pentagon costs) seems valid.

This would be a spectacular waste of money if greenlit. We currently have exactly zero actual reason to think this is going to find anything new.

While Sabine Hossenfelder (Youtube) has a somewhat mixed record, her arguments against this project seem believable.

People who knew less than nothing about physics came out in droves to oppose the LHC, claiming it could create a black hole and end the world. I wonder what they will say about the next one.

That it wil fail to create a black hole and end the world?