The original 12-game series has ended in a 6-6 tie with each player winning one game and the rest all draws. The last game had Magnus Carlsen playing white and observers had hoped he would go for a win against Sergey Karjakin but he seemed to be content to play for a draw after just 30 moves lasting only 45 minutes.

This may be because the tie-breaker rules consist of games that have ever-increasing time constraints and Carlsen is one of the best in playing rapid chess, though Karjakin is no slouch either.

The match will now go to tiebreakers, 25-minutes “rapid” games, beginning Wednesday at 2 PM ET. There will be four of those. If there’s still no winner, the 2016 World Chess Championship goes to five-minutes blitz games.

Carlsen is not only the world’s number-one ranked player in classic chess — he’s also number one in rapid and second only to China’s Ding Liren in blitz, according the the most recent FIDE rankings. Like any top Grandmaster, Karjakin is no slouch at either rapid or blitz, but Carlsen is, on paper, a lot better.

Oliver Roeder had some interesting insights into the role of technology when it comes to the spectators who attended the matches to see it live. Although they are in the hall, many are not watching the players but on a monitor, just as if they were at home.

Watching the World Chess Championship is an essentially digital experience. The players still play analog — they sit in chairs in the same room as each other, pushing boxwood pieces across a rosewood and maple board. But the pieces are equipped with sensors that digitize the moves, sending them to phone and laptop screens around the world. Even at the venue, only a small minority watch the actual human players through the thick one-way glass in the viewing hall. Far more stare at large flat-screen monitors, or at smartphones or tablets, exactly as they’d be doing were they watching in their living room.

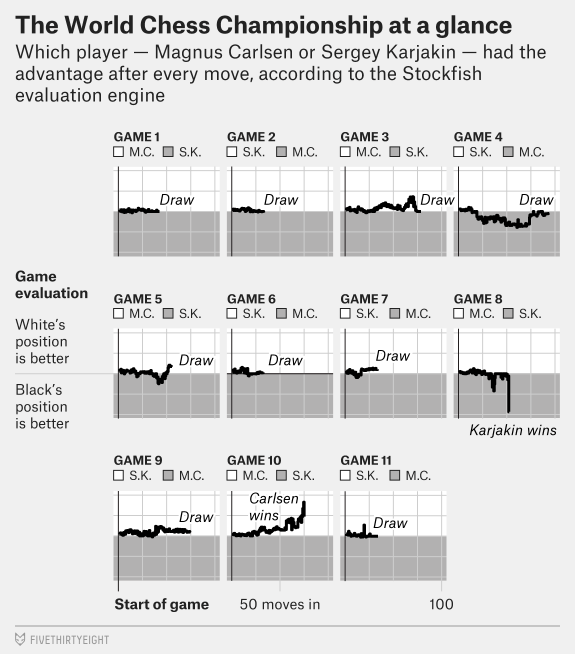

He says that many observers use computer programs like Stockfish to see who is doing better at each stage of the game

After a few split-seconds of considering a position, an engine like Stockfish spits out an “evaluation.” This is a single number, measured in fractions of a pawn. If the number is positive, the computer sees the position as better for white, and if it’s negative, better for black.

He gives Stockfish’s play-by-play analysis for the first 11 games.

Too many defensive draws are bad for the game. Maybe if they become too abundant, the rules might change to mix up the time limits for the regular 12-match series as well with different point weightages for the different types, so that the champion will be the person who can play best under a variety of time constraints.

Why not make the time limit dynamic? For example, each draw takes away ten minutes from the next play, and each win gives ten minutes more time.