Pope Francis has created an interesting situation when it comes to political alliances. On the one hand, he has said some very positive things on the injustices waged against the poor, the evil of massive inequality with the rich getting much richer at the expense of the poor, and the importance of combating global warming and the resulting climate change.

But when anyone commends him for these steps, others are quick to point out (rightly) that he also is continuing many of the awful policies of the church and of his predecessors and that for every good position the church adopts, one can point to a bad one. The Catholic Church opposes the death penalty but also opposes contraception and abortion. His call for the improvement in the conditions of the poor and fighting climate change are contradicted by the church’s reluctance to endorse reductions in population growth that would greatly assist in both. The emphasis on helping the poor seems hypocritical for the head of an institution that has a vast amount of wealth. And his calls for inclusivity are contradicted by his opposition to same-sex marriage and LGBT rights. And of course, the very fact that he is the head of a huge institution that has committed and then covered up the most appalling abuses by its clergy have resulted in the Catholic Church being compared to an organized crime syndicate.

So is Francis a friend or foe to progressives? I see many articles arguing as to whether, in the context of US politics, the pope is more helpful to the Democrats or the Republicans.

I think these are not useful questions to pose. It presumes that in creating alliances of people and organizations, we need to make judgments on the overall worthiness of such groups before admitting them. This is done by weighing their good and bad qualities and then deciding, based on some metric, whether on balance the people and organizations are friends or foes.

I don’t believe this is a very useful way to achieve progressive goals. For one thing, people and organizations are complex entities with multiple goals and getting perfect congruence is unlikely. Furthermore, there is no consensus on how one weighs the different positions of a person or organization to determine whether they are a net positive or negative. For some people, a position on one issue can be dispositive and make all other considerations irrelevant in making such a judgment, while for another a different issue can be critical. This can result in endless debates as to whether someone or something is worthy of being considered an ally or not.

But such a binary decision is only necessary in elections when one is forced to decide on a single person to vote for. When it comes to working to achieve specific goals, making that kind of summative judgment becomes less important and even unnecessary.

My own preference is to act along the lines suggested by Lord Palmerston in 1848 when he said in the British parliament, “I say that it is a narrow policy to suppose that this country or that is to be marked out as the eternal ally or the perpetual enemy of England. We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.” This has been subsequently paraphrased by many people and is now often abbreviated as, “We have no permanent friends or enemies, just permanent interests”.

I am willing to consider as an ally on any specific issue anyone who agrees with me on that issue even if I disagree with them strongly on other issues. So I am quite willing to consider the pope my ally one day on the issue of fighting inequality and economic injustice and to fight him vigorously the next day on the issue of same-sex marriage. And the same goes for any other person or organization.

This policy also has the benefit of avoiding endless discussion of motives. For example, there are occasions when people whom one considers reactionary on some issue say that they have reversed their position. This raises the question of whether the conversion is genuine or hypocritical, and such judgments are hard to make unless one sees consistency over a long period of time. If a politician who was an ardent supporter of flying the confederate flag now says that it should be taken down, that may well be due to swaying with the current political winds and not a genuine change of heart. But how much should that matter? As William Greider said, “Important social change nearly always begins in hypocrisy.” Getting people to say the right things is important even if they don’t mean it and we should welcome those who do so.

We should be aware of the danger of people saying the right things just to lull opponents so that we will treat them more gently when they say and do the wrong things. We should guard against the trap of giving people a pass on some issues simply because they agree with us on others.

In short, we have to keep in sharp focus what our goals are and the need to get as many allies as possible to achieve those goals, rather than on the overall purity of the allies.

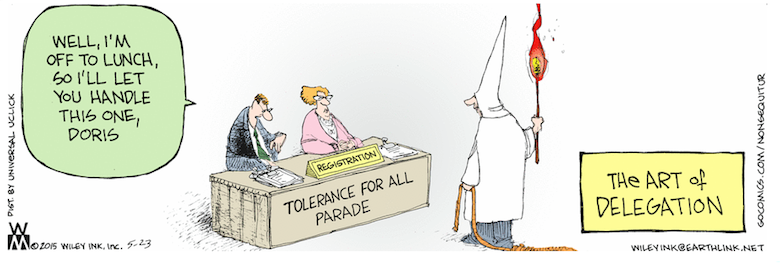

Like all political positions, this one is not without its problems as can be seen by pushing it to extremes. How far can one go in overlooking the negative positions of some groups? As an example, suppose a neo-Nazi group or the KKK wants to join a coalition of forces that is organizing a rally on the issue of fighting global warming. Should they be allowed to do so? By accepting them, wouldn’t we be tacitly helping them gain mainstream acceptance for their other views?

I think a case can be made for an exception to the rule I am advocating and that there are some people or groups who are simply beyond the pale and can and should be excluded from the coalition even if they happen to agree on the one feature the coalition is built around. Fortunately, in most such cases it is usually easy to get agreement among the other coalition partners on these particular groups so it should not be too hard to arrive at a consensus to exclude them.

A problem with that though is when there are issues with internal consistency…Bringing population sizes down is a MAJOR if not THE major challenge addressing global warming…IOW, you can’t be FOR one and AGAINST the other…Complicated stuff for sure….

No, it isn’t. The key period for avoiding potentially catastrophic climate change is the next few decades. The only way global population is going to fall over those decades is if very large numbers of people die from wars, epidemics or other such disasters. Most population growth is now occurring among populations which have far lower per capita production of greenhouse gases than average, let alone that of the rich Americans and Europeans who most need to change their behaviour in order to cut emissions. Global population growth rates have roughly halved since their 1960s peak, and continue to fall. Since the 1990s, even the absolute net annual increase in global population has fallen. None of this means we should not continue to campaign for full access to contraception and abortion for any woman who wants it, and to raise the status of women worldwide -- things absolutely worthwhile in themselves, and on which we will clearly be fighting the Catholic Church. These measures will almost certainly suffice -- along with (unstoppable) urbanisation -- to halt global population growth this century, but that will not come anywhere near adequate mitigation of climate change. As far as that is concerned, focusing on population simply lets those actually responsible for most emissions off the hook -- and that is, indeed, very often its purpose.