Debt cutting frenzy has been rampant across North America and Europe, with ‘everyone’ (i.e., politicians, elite media, and the oligarchs) arguing that if the deficits are not reduced by cutting spending on social services, countries risk ruin. This phony consensus has been driven by pseudo-grassroots campaigns like ‘Fix the Debt’ and the Simpson-Bowles ‘Catfood Commission’, while standing in the shadows and pushing this agenda is billionaire Pete Peterson who has poured half a billion dollars into trying to cut Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and other social programs.

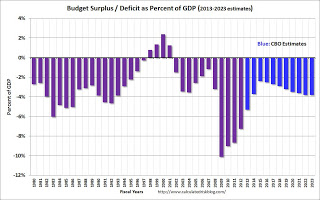

This sense of debt panic has continued despite the fact that the Congressional Budget Office studies suggests that the deficit as a percentage of GDP has been steadily declining in the last few years. After a high of around 10% in 2010, it dropped to 5% in 2012 and is expected to drop to just 3.7% in 2014 and 2.4% in 2015 before slowly rising again.

This sense of debt panic has continued despite the fact that the Congressional Budget Office studies suggests that the deficit as a percentage of GDP has been steadily declining in the last few years. After a high of around 10% in 2010, it dropped to 5% in 2012 and is expected to drop to just 3.7% in 2014 and 2.4% in 2015 before slowly rising again.

Where did this deficit cutting mania come from? It became the conventional wisdom apparently out of the blue but it appears that its main impetus was in a 2010 paper by two Harvard economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, who published a study that claimed to show, based on their long-term analysis of the data on many countries, that when the size of a country’s debt reached a threshold of 90% of the GDP, its growth rate dramatically declined and went into negative territory. This kind of thinking led many countries, like the UK, to drastically cut spending, causing much suffering.

The radio program Marketplace describes how influential this paper, and its authors, was in setting the budget agenda in much of the developed world.

The pair met with 40 senators in 2011 and “they told them, you need to act now and that we can’t afford to spend more money to stimulate the economy.” Also reading research by the two Harvard economists were budget chairs from both parties, then Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, the Simpson-Bowles Commission and financial leaders in countries overseas. “When we were talking about the budget deficit and the debt in 2010, 2011 and 2012, everybody had this 90 percent threshold on their minds,” says [Quartz business reporter Tim] Fernholz.

…

“When politicians around the country and in fact around the world were deciding what to do to save the economy after the recession, they were reading this paper and it was scaring them,” says Fernholz. “And it was making them think, we need to cut the debt now if we want to save the economy.”

The mania to cut government spending in order to reduce a nation’s debt was fueled by this belief that high debt was hurting growth

There has been quite a bit of chatter in the last two days in the world of academic economics about the discovery of serious errors in this paper. As Mike Konczal says, right from the beginning there were those who criticized the study and said that they could not replicate the author’ results (always a warning sign), even though the raw data was publicly available. The problem was compounded by the fact that the authors for a long time did not release to other researchers the spreadsheet that had their data analysis. Furthermore, the causality relationship was not clear, even if one accepted their results. Does high debt cause slower growth or does slower growth cause high debt?

Now Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash, and Robert Pollin at the University of Massachusetts, after also being unable to reproduce the results, did manage to gain access to the spreadsheet analysis and have published a paper that challenges the Reinhart-Rogofff conclusions and says that they arose from serious errors.

Herndon, Ash and Pollin replicate Reinhart and Rogoff and find that coding errors, selective exclusion of available data, and unconventional weighting of summary statistics lead to serious errors that inaccurately represent the relationship between public debt and GDP growth among 20 advanced economies in the post-war period. They find that when properly calculated, the average real GDP growth rate for countries carrying a public-debt-to-GDP ratio of over 90 percent is actually 2.2 percent, not -0.1 percent as published in Reinhart and Rogoff. That is, contrary to RR, average GDP growth at public debt/GDP ratios over 90 percent is not dramatically different than when debt/GDP ratios are lower.

The authors also show how the relationship between public debt and GDP growth varies significantly by time period and country. Overall, the evidence we review contradicts Reinhart and Rogoff_’s claim to have identified an important stylized fact, that public debt loads greater than 90 percent of GDP consistently reduce GDP growth.

I can understand the spreadsheet formula coding error. We all make mistakes and while this one is particularly embarrassing and suggests sloppiness, it does happen from time to time. Much more troubling is the way some data were omitted (those of countries where the data went against their hypothesis) and some of the techniques that were used in analyzing the data. All three errors pushed their results in the same direction, of making their conclusions more dramatic and raising alarms about the 90% debt cliff.

Take just one of the analysis problems, the way they averaged the statistics over countries. Although economics is not my field, the practice of taking averages of averages is always something to be done warily and avoided if at all possible, because each average may be weighted differently. In fact, in my introductory physics courses, I often give students a little problem. If a car travels the first 300 miles of a journey at an average of 50 miles per hour and the second 300 miles at an average of 75 miles per hour, what is the average speed for the full 600 miles? The answer is not 62.5 mph, the average of the two average speeds as some students mistakenly assume. It is in fact the total distance (600 miles) divided by the total time (10 hours), giving 60 mph. But while my introductory physics students can be excused for their naivete in jumping to such a conclusion, it is shocking to find seasoned researchers doing this.

The reactions to these new revelations have been widespread and harsh in their condemnation of Reinhart and Rogoff. Paul Krugman says that he never believed the Reinhart-Rogoff results in the first place but that he is disturbed by their response to the recent criticisms, where they seem to be deflecting attention to irrelevancies.

As Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research says, “If facts mattered in economic policy debates, this should be the cause for a major reassessment of the deficit reduction policies being pursued in the United States and elsewhere. It should also cause reporters to be a bit slower to accept such sweeping claims at face value.”

But of course, facts don’t matter to our elite world of pundits and media, if those facts stand in the way of their greed and ideology. So I don’t expect the complete undermining of the evidentiary basis for the current austerity policies to have any effect on the way that the media reports on this issue.

As cartoonist Tom Tomorrow says, Obama will continue to seek a grand bargain to cut the deficit by gutting Social Security and Medicare.

Because ‘we all know’ that the current deficits are dangerous, no?

The public debt of the USA is, to the republicans who dishonestly winge and winge about it, nothing more than a stick to continually beat Obama with. They had no problem with it when they were incurring it with tax cuts, illegal war expenses and other costly programs intended to buy votes. They only apparently discovered its dangers after Obama entered office. Had McCain been elected POTUS you never would have heard a word unless from a few democrats…..

OT: what concerne me most about Obama is that, after the way he has been treated by the republicans for the past four years plus, he would still rather do deals with them than with his own party….what’s with that?

Keep in mind that the conservatives have been very disingenuous with the issue in 2 very important ways:

-- They show the value in dollars which looks huge and obviously always grow since the value of the dollar is always less as the years go by. This allows them to make 2002 (for example) look much, much better than 2013.

-- They focus on 2009 a lot. Of course, the FY 2009 budget was created in 2008 (federal fiscal years are October thru September, so the FY 2009 budget started Oct 2008) before Obama took office, but they strongly imply (if not outright state) that it is Obama’s budget.

Of course, if the Bush tax cuts were actually halted, much of this issue goes away very, very quickly. And, no, getting rid of the tax cuts will not negatively impact hiring or wages except in the rare cases of the big a-holes that are just being vindictive.

When the Harvard clowns were doing their “calculations” of economies, they deliberately left out the economies of several nations. The most notable exclusion was Canada, which has had (arguably) the strongest economy in the world since 2008, and others such as Belgium and Australia which also have fared well in recent years.

Normally, those with agendas count the hits and ignore the misses when fudging figures. This time, they counted the misses and ignored the hits.

Why does Pete Peterson hate America?? Is it because he’s got his billions, that he wants everyone else to suffer? It’s not enough that he’s rich, he wants the poor to be poorer? What the fuck is wrong with these people?

I don’t understand why Obama keeps waving his willingness to carry out the not even right of center but very right “grand bargain”. I more or less expect the general media to fall in line with the zeitgeist and flavor that position with whatever is in vogue in corp. America. What I didn’t fully expect was the so called moderate voices who were happy to ignore deficits under Bush the Lesser but more or less flipped to caring a lot once Obama was in the Whitehouse.

Given that I’ve never heard that line of reasoning over here, let me suggest that this might be a rather US-centric view of things.

For one, over here in Germany, attempts to cut down the debt go at least back to 1998, when that was one of the big arguments for electing the social democrat Schröder and ousting conservative chancellor Kohl.

For another, there are usually two lines of reasoning given over here: for one, the more debt we have, the more tax money goes into serving the debt instead of any of the other things the government should spend money on. (And of course, in the end, the harder -- read more expensive -- it gets to make new debt.)

And the other, we want to keep the Euro from inflation. Inflation is what governments usually do when they get in trouble paying for their debt (also known as printing money) -- it’s a kind of invisible tax on money. A few percent is fine, more than that is unhealthy.

As for doing it just with cuts on the social side, this is of course highly contested -- starting with a social democrat government is sort of like “only Nixon could go to China”, and these days this party tries hard to disassociate themselves from the uglier parts thereof.

On the other hand, whatever the cause, we are rather well off as a nation these days, compared to the rest of Europe or the US. There’s a reason people listen to Merkel on this topic -- I don’t happen to think it’s a good reason, but what do you expect?

Oh, and of course, a large part of the current frenzy is about large banks crashing and taking large chunks of the economy with them, a problem that, IIRC, originated in the US. National debt is only incidentally related, for example when small nations try to prop up big banks. Which is why we (much too slowly) are working on rules changes to make this kind of problem less likely -- more bank reserves, more insurance against bank defaults, less incentives for bank managers to grab the fast money, so we don’t get caught with our pants down again.