Existence is not Great

A core assertion of Ontological is that it’s better to physically exist than to be a concept. I’m not convinced, and to help illustrate the point I propose a simple thought experiment.

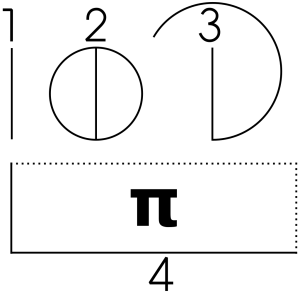

- Picture a vertical line, which we’ll declare to be one unit high.

- Place a circle around it with a diameter of exactly that line; if you’ve pictured this correctly, you’ll have a circle split in two.

- Now, mentally undo the part of the circle that touches the bottom of the line, as well as the top part of the line on the left side. Unwrap it counter-clockwise from the top, keeping the left-most portion anchored to the top of the vertical line, until the line is perfectly horizontal and at a right angle to the original line.

- You now have two sides of a rectangle. Complete it by extending a horizontal line from the bottom of the vertical line with the same length as the upper horizontal line, and a vertical line from the end of the upper horizontal line with the length of one unit.

The area for a rectangle is the width times the height. We know the circumference, or length around a circle is π times the diameter of that circle, which in this case is π units. So with a width of π units and a height of our circle’s diameter, or one unit, that rectangle has an area of exactly π square units.

If you had difficulty, the following diagram should help you. Conveniently, this diagram will also prove my point:

The final rectangle in your mind is exactly π square units big. The rectangle in this diagram is not. In fact, no real-world diagram will ever be exactly π square units.

For argument’s sake, we’ll say the rectangle is exactly 10cm wide, and the diagram is printed at 472dots per centimetre.[26] The width of this rectangle is thus 4,720 dots, and the height is 1502 dots, for an area of 7,089,440 dots. To convert that to “units,” we need to divide by the size of one square unit in dots, which is 1,502×1,502 or 2,256,004 dots. According to my math, that rectangle is about 3.142477 square units in size. This differs from π after the third decimal place.

The reason is pretty clear. π is an irrational number with an infinite number of decimal places; by definition, it can never be represented by one integer divided by another, or by counting a finite number of elements. And yet if we construct this diagram in the real world, both the width and the height must be finite numbers. Even if the width of the rectangle was the size of the visible universe, it would still be a finite number of atoms in area, and our answer would be wrong somewhere around the 36th decimal place.

There’s no escape from this problem, either. No matter how you try to represent π in the real world, you’ll be forced to use a finite number of decimal places to represent a number with an infinite number of them. And yet, what’s impossible in the real world is easy in your head. You don’t need to convert π to a decimal number, you can treat it as a concept and dodge around the problem. As a consequence, the rectangle in your head is exactly π square units in area.

This confirms something I’ve observed as an artist. Like Anselm’s painter, I too have had a vision of a finished drawing or photo in my head; unlike him, the finished product is rarely more than a shadow of what’s in my head. Something always goes wrong; a line falls out of place, a photo has a branch that’s poorly placed, and so on. The exceptions are usually because I accidentally found an improvement while creating the work, and not through perfect execution.

The Triumph of Irrationality

I’ve also got a beef with another assertion of Ontological, that it’s impossible to think of any being greater than god.

If you’ve heard of Buddhism, you’ve likely heard of its most famous variation, Zen. Part of that sect’s seductive quality comes from an emphasis on “kōans,” or questions that have no rational answer but instead are intended to provoke an enlightened train of thought. Here’s the most famous of them:

“Two hands clap and there is a sound. What is the sound of one hand?”

(Hakuin Ekaku)

That question cannot be logically answered,[27] yet Hakuin had no problems asking it and we had no problems contemplating it. Given a little thought, you should be able to come up with your own kōans: What is the colour of an object in perfect darkness? What is the sound of empty space?

Kōans show that we have no problem thinking irrational thoughts. The Ontological proof uses reason to prove god, however. In order to do this, it assumes that god must be rational. If he is not, he could not be described by reason, and if he could not be described by reason, he could not be proven by it either.

But if a god must be rational, and our thoughts don’t need to be, we can contemplate things greater than the gods. Let’s try it: There is something greater than a god. The consequences of that sentence are not logically valid, yet I had no problems writing it and you had no problems understanding it. If we shift our assumptions, we can make it valid; I’ll use this in the Morality proof later on, for instance.

If we’re not bound by rationality, while god is, then we can easily think of something greater than god, and another assertion is shot down.

Anselm realized this loophole, and tried to close it in Chapter 4 of Proslogion. He separates thought into two categories:

For a thing is thought in one way when the words signifying it are thought, and it is thought in quite another way when the thing signified is understood. God can be thought not to exist in the first way but not in the second. For no one who understands what God is can think that he does not exist.

(Chapter 4: “How the Fool Managed to Say in His Heart That Which Cannot be Thought”, as translated by David Burr)

The problem with Anselm’s counter-counter is that it doesn’t address the counter-argument at all. He clearly wants to put “a being greater than god” in the “signified but not understood” category, where he can safely ignore it, but he doesn’t say why it belongs there, let alone why his categories exist in the first place.

In order to decide which category that sentence goes into, you have to understand the sentence first. For instance, which of the two gets “Yd.p. lprxaxnf co br Ire?” That might be a meaningless statement, making it impossible to understand, or it might have meaning in a language or code you’re not familiar with. In contrast, “There is something greater than god” can be easily understood and thus placed in a category. But because you understood it, there’s only one possible placement: things that are “signified” and “understood.”

You may not be aware of all the rational implications of that statement, or you might know them better then I do, but the underlying concepts must be clear to you before you can make a rational decision. Irrational decisions are another beast, but they only prove my point: the irrational trumps the rational.

Anselm’s defence doesn’t work, and my counter-example still stands.

This cuts the other way, as well. Merely being able to state something does not make it rational or logically justified. The fourth “distilled” proof falls into this trap. “The existent perfect being is existent” is true, in the same way that “the existent @#^*$ is existent” is:

- “The existent ___ is existent” depends on the assumption “a ___ exists.”

- If that assumption is true, then there’s no need for the proof!

- If that assumption is false, then the proof is contradictory and we can conclude anything we wish from it, including the existence of whatever we want.

The fifth earns a medal from me for squashing three separate proofs into one. There’s proof from Witness (“if one person is convinced a god exists, god exists”), proof from Popularity (“multiple believers can’t be wrong”), and just a sprig of Ontological (“the word ‘God’ only means something if a god exists”). Unfortunately, it falls flat on that last assertion, as the trio of Faust, Bilbo Baggins and the Jabberwocky will swear to. We’re surrounded by fictional, non-existent things that provide us with meaning, by setting an example or just giving us a good time. This extends to science as well; Niels Bohr expanded on Ernest Rutherford’s model of the atom to create the boringly-named Rutherford-Bohr model, which has very little in common with the real layout of an atom but is easy to teach. And so it is taught.

[26] For readers who think in imperial units, that’s 3 15/16ths inches and 1200dpi respectively.

[27] It’s a common misconception that kōans have no answer. To the contrary, every kōan has an answer, though that answer varies from Buddhist Master to Buddist Master. For instance, Zhàozhōu’s answer to “Does a dog have Buddha-nature or not?” to one of his students was “Wú,” Japanese for “no.” To another, he replied “yes.”