Scanners

No doubt, this seems like I’m stretching. How can spiritual transcendence be the same as the non-spiritual kind? The two seem very different.

In the past two decades, a new term has sprung up: neurotheology. Scientists armed with brain scanners have begun using them on the devout, looking for any interesting patterns. Unfortunately, most approach this from the theological side, either taking the existence of a god as fact or explicitly stating they are uninterested in its existence. This tends to colour their interpretations of the data.

Still, there are interesting nuggets to be found. For instance, Andrew Newberg has compared the minds of believers while they meditated to those of atheists doing the same thing, and found no difference between the two. In study after study, this pattern holds:

When we look at how the brain works, it has a limited set of functions. So if one has a feeling of euphoria — whether one gets that through sex or religion or watching your team win the championship — it’s probably going to activate similar areas of the brain. There’s a continuum of these experiences. […]

Are we really capturing something that’s inherently spiritual? This is a big philosophical question. If the soul or the spirit is really non-material, how does it interact with us? Of course, the human brain has to have some way of thinking about it. Perhaps the most interesting finding I could have would be to see nothing change on the brain scan when one of the nuns has an incredible experience of transcendence and connectedness with God. Maybe then we really would capture something that’s spiritual rather than just cognitive and biological.

(Andrew Newberg, interviewed by Steve Paulson for Salon. Sept 20, 2006. http://www.salon.com/books/int/2006/09/20/newberg/print.html )

If there were some legitimate difference between believers and non-believers, we’d expect some difference in the brain itself. Instead, it seems that behaviour is far more influential than belief; by merely repeating the same actions, we see the same patterns across both categories.

Note that this is not disproof against a god by itself. Others have used the very same observations to claim that everyone has a spiritual connection, even those that don’t believe in it. This is a valid interpretation, but it doesn’t line up with the claims of believers. People who don’t believe or are in the wrong religion are fundamentally different from those in the right religion, since only the last has true contact with the real god or gods. We should see this difference reflected somewhere. Secondly, it depends on the existence of a god to make sense. This is a problem, since the alternate explanation does not depend on the existence any god, it only discounts that the brain has a special channel to the gods, but the theory is otherwise agnostic about them. We can begin sharpening Ockham’s Razor.

But first, there’s more evidence to ponder. The Pentecostals, a Christian sect, believe that “speaking in tongues” is the highest form of worship. Also known as glossolalia, it’s a sort of spoken gibberish, sometimes while writhing around on the floor, and is claimed to be the sign of God speaking through those people. This makes an interesting test case, since both prayer and glossolalia attempt to contact the same god through different behaviours. If both have the same brain activation patterns, this would be clear proof that a deity was involved; if the brain and body were material things, different external behaviour must correspond to a different internal state.

Newberg’s studies show that the brain states are different. He’s catalogued the regions of the brain involved in both activities:

- thalamus: linked to processing the senses. More active than usual in both prayer and glossolalia.

- temporal lobes: linked to processing our emotions. More active in both.

- frontal lobe:[167] linked to our ability to concentrate and focus. More active in prayer, but inactive in glossolalia.

- parietal lobe: linked to feelings of self, and how it relates to the world. Less active in prayer, no effect during glossolalia.

Interesting, isn’t it? When people pray, they focus on losing their sense of self and the external world, feeling an emotional lift they think is a real experience; at the same time, the corresponding areas of the brain fire up or shut down, according to need. Meditation has roughly the same effect, and roughly the same brain patterns. When people speak in tongues, losing their focus (but not their sense of self) to an emotional lift that feels very real, the brain also changes accordingly. The areas of their brain responsible for language do not light up, and linguists studying the sounds uttered during glossolalia can find no evidence of linguistic structure. Note that every activated region is not reserved for religious use, but one that we discovered being used by some secular activity.

This pattern is exactly what we’d expect if the brain was purely material, and the feelings attributed to religion were just existing ones put to a different use. This pattern is not what we’d expect if a divine being were beaming those feelings directly into our minds.

Still, this is not a dis-proof of the gods; I can find no studies that checked if the feelings of transcendence came before the brain activity, for instance, which could have provided evidence for the theist side. It’s quite possible that a god grants us these feelings by tugging on the appropriate portions of the brain. On the other hand, if we said this pattern were the actions of a god we’d be assuming a god existed, while if we claimed it was purely material we’d make no such assumption. Ockham’s Razor says we should go with the material theory, rendering the gods irrelevant yet again.

Precision from the Non-Precise

There’s an odd hypocrisy to this proof.

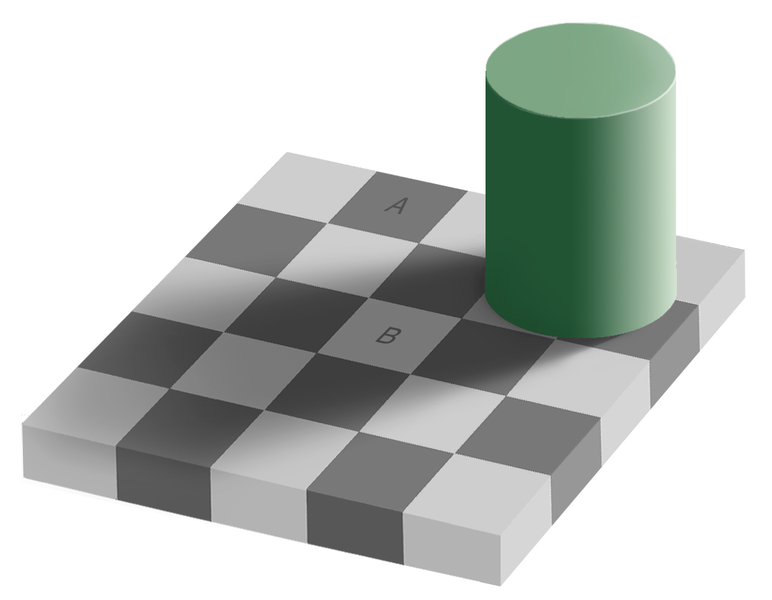

Have a careful look at the two squares, and tell me which one is lighter:

Sorry, that was a trick question: both squares have the same tone.

Are you feeling any anger at your senses? I doubt it, we’re happy to admit they lead us astray. That goes doubly so for the religious, because it allows them to dismiss a lack of physical evidence and invoke the Transcendence Proof.

[FUTURE HJH: I left this bit incomplete. My basic plan was to link to Descarte’s invocation of God as a fundamental belief. This website provides a basic sketch.]

Why, though, are we so content to accept this inaccuracy? We rely on our senses to an astonishing degree, after all. I think it’s a safe assumption that you’re absorbing this text through your senses. Was any part of it blocked by a malfunctioning sense? Did you have to repeat certain passages, because the words kept changing on you? Did the page suddenly zip away or flip upside down? Think of all the possible moments, and all the possible ways, this text could have been screwed up by your senses, and total up how many of them have happened so far. For most people, I’m sure, that total is comfortably close to zero.

Now total up the number of moments that went right. Are they near zero? Or substantially higher?

Let’s say you’re one of the unlucky few. Pretend that on average, one out of every ten words you absorb were not written by me. Does that make this book unreadable? Certainly not. If you scan each passage twice, the odds of a word being wrong both times drop are one in a hundred. Three readings pushes the odds down to one in a thousand, and the more readings you’re willing to do, the more confident you can be that you’re reading what I wrote.

What if we don’t know the odds? Fortunately, the English language has roughly 200,000 words, so there are far more ways to be wrong than right. The odds of the same wrong word being picked twice in a row are roughly one in 200,000, so if you read the same word twice you can be quite confident it’s the right one. Switching to a language with a ridiculously small vocabulary still doesn’t stop you from moving forward, it just requires more scanning.

We don’t fret over unreliable senses because it’s trivially easy to make them reliable enough. Consider the colour puzzle; in that case, multiple samples will never lead you to conclude both squares are the same shade. However a simple mask, cut out of paper, will quickly make the truth obvious. When you start to employ multiple senses, and use or augment them in multiple ways, you can be quite sure they haven’t led you astray.

What about our feelings, though? Can they be fooled, like our other senses? It would be very odd to claim that easily verified senses like vision are unreliable, and yet fuzzy, non-specific feelings are perfectly reliable.

If they can steer us the wrong way, then how can we trust them without putting them to the test? How can we rely on them to tell the truth, without looking for and ruling out alternate explanations first?

[167] From one ear, draw around the front of your head at eyebrow-level to the other ear, then return by going over the very top of your head. You’ve just outlined the boundaries of your frontal lobes.