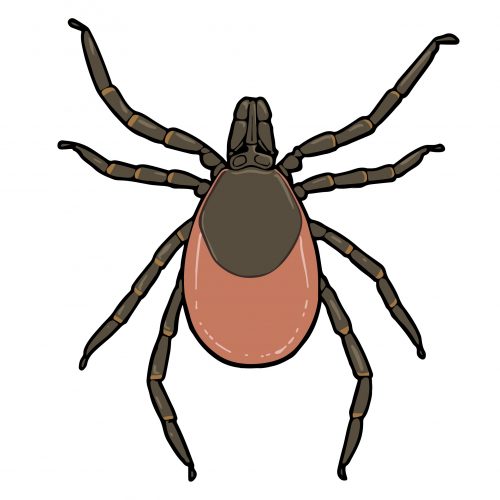

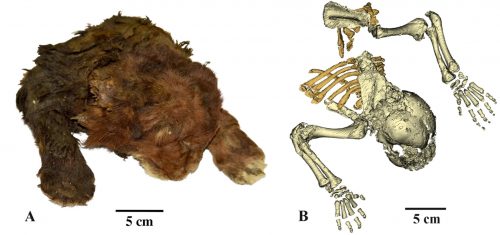

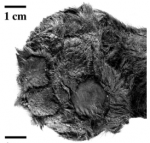

This is a female Latrodectus mactans.

This is a male Latrodectus mactans.

I brought them together this morning. The female is plump and mature. The male has large, engorged palps. This is what they look like together.

They did not mate today, although the male spent a lot of time scurrying around and tentatively plucking at the web. At least she didn’t eat him. I put a video of the anxious, fruitless male on my Patreon.

I left them to honeymoon overnight. I’ll check on them tomorrow.