The other day, when I was taking a tour of the UMM EcoStation, I learned that they are currently leasing a few acres to a local farmer, but that there were restrictions on what he could plant. No corn! No planting corn in our ecologically conscious field station, because corn fields get soaked in neonicotinoids, a potent pesticide.

Of course, as we returned home, we drove past immense fields of corn everywhere.

Neonicotinoids are great for killing insects — they’re a nerve poison that binds to acetylcholine receptors, found in the central nervous system of insects, triggering excessive activity and killing them with overstimulation. It kills bees and butterflies and fireflies, those charming and charismatic creatures everyone loves, but also flies and spiders, which no one seems to care much about. Well, except maybe me and weirdo entomologists.

It’s been a poor summer for spiders, but then, I’ve noticed them declining in numbers for years. This summer, though, it was particularly obvious — in previous years, my lawn has been dotted with little tents, the webs of grass spiders, that are vividly obvious in the morning dew. This year…I’ve seen a handful, and some mornings, there are none at all.

Orb weavers haven’t been common around here. We’ve looked at the local horticulture garden, and aside from the rare tetragnathid, they’ve been mostly absent. It’s getting a bit creepy. Maybe you’re not as fond of spiders as I am, but you know you’re in trouble when levels of the food chain start dropping out.

It’s not just me. When we spot one or two monarch butterflies now, it’s noteworthy, and my wife will drag me out to the garden to see. Years ago we’d see huge flocks of them coating trees. It’s worldwide; butterfly populations in the UK are down.

Richard Fox, head of science at Butterfly Conservation, said: “The previous lowest average number of butterflies per count was nine in 2022, this latest figure is 22% lower than that, which is very disturbing. Not just that, but a third of the species recorded in the Big Butterfly Count have had their worst year on record, and no species had their best. The results are in line with wider evidence that the summer of 2024 has been very poor for butterflies.

“Butterflies are a key indicator species; when they are in trouble we know that the wider environment is in trouble too. Nature is sounding the alarm call. We must act now if we are to turn the tide on these rapid declines and protect species for future generations.”

Crashes in flying insect populations including beetles and wasps have been widely observed during the summer after a prolonged wet and cold first half of the season.

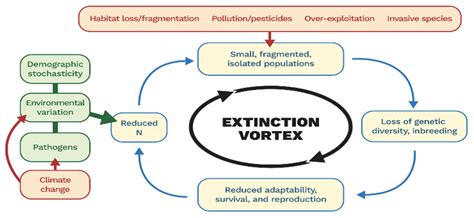

Weather is part of the reason — we also had a weirdly wet early summer here in Minnesota, and our trees are showing signs of stress. This isn’t the only stressor in our environment, and it’s rare to be able to blame extinctions on a single source. When you get multiple factors harming a population, that’s when you get an extinction vortex.

There is something going on here. You should be afraid. I am.

Word. Have you also noticed the lack of bugs on the car? It used to be that the car was covered in dead bugs every summer, I haven’t seen that in years. It ain’t right.

Yes. My kids have noticed, too. My granddaughter has never seen a car caked with a thick sheet of dead bugs.

I don’t fear it anymore. After years of disappointment and existential torment, I’ve finally accepted that humanity is going to widely fuck itself and everything around it. We just don’t have the collective smarts to overcome ourselves and our tribal greed. Apologies to all the young people, you don’t deserve this.

Yeah. Like I mentioned in a discussion on climate change denial here a few days ago, all the destruction is becoming fucking obvious. Back in the 80s you needed scientists to analyse temperature records and observe population to see the effects of what we are doing, now everyone can see it in their own yard.

But most of us don’t want to see it, just don’t care about it. I get that people are worried about losing their income when environmental policies impact the job market, I share their worries about one’s future in this shitty capitalistic nightmare. But what good is my job and my income when the biosphere I’m part of is dying?

On the other hand, many people seem only interested in their big, fast cars, tons of plastic crap from China to buy cheaply and then junk and love to make fun of or are hostile to those who try to make at least a bit of difference.

I’m just glad I never had children and I’m unlikely to get very old.

I live few hours north of Toronto Ontario and I have to walk slowly around my daughters gardens and house because there are so many Orb Weavers giant webs and my studio has a lot of those gorgeous black velvety jumping spiders and little baby ones.

This cartoon seems apposite

ISTM that with our current state of technology, we could build harvesters that could harvest multiple types of crops. Then you could plant a field in multiple types of crops and you don’t need so many pesticides because the bugs attracted to corn perhaps are repulsed by soybeans. One could plant huge fields in differing rows of crops, and not only would that reduce insect damage, it would insulate the farmer from crop failure. Did bad weather destroy your corn plants? No problem, 80% of your fields were planted in other crops.

I noticed a few years back a tremendous drop in fireflies (lightening bugs as we call them) around my yard. Over about a three-year period, they went from plentiful, non-stop for hours, every night to less then ten sightings per night. There has been significant development in my town and much close to my house so I’m sure that had impact. Also noticed a drop in all types of butterflies. This year there SEEMED to be a slight increase in the sightings of these critters. Keeping my fingers crossed.

Silent Spring has come it seems. Or is coming soon.

It’s Spring in my hemisphere. Silent every season almost everywhere really I fear.

More like Dust, by Charles Pellegrino. (Do not read unless you want a few sleepless nights!)

Dennis K@3:

Problem is, we’re the buggy beta version. The first humans able to build civilizations at all, as of somewhere south of 15000 years ago. Sometime in the geologically extremely recent past we went from not-quite-smart-enough-yet to just-barely-smart-enough … to make a credible attempt now and again. Apparently keeping one going, stably and sustainably, takes more and perhaps we’re not there yet.

On the long-range upside, though, the coming turbulent period will likely apply a lot of selective pressure favoring those populations able to keep a (small-scale) civilized society running through serious instabilities in its environment and access to trade … perhaps enough to spawn a Homo novus more capable of maintaining a civilization for the long term.

But evolution is not linear, and other strategies might work too, including “go back to H. erectus or Neanderthal like traits” or a sideways move of some sort, which could be anything from “smaller, with lower food requirements, and more easily able to switch between a feral rugged-individualist lifestyle and a social one” to “a fully eusocial hive species of mostly sterile female workers, much more stable against internal competition”. Selfish individuals beat altruistic individuals in groups, while altruistic groups beat selfish groups, so a eusocial neohuman species might outcompete the other possibilities up there.

Or we could see multiple speciations, a radiation of several kinds of human on the far side of the bottleneck, rather than a shift to a different single one. Since we’re omnigeneralists, it’s unlikely these will easily coexist in a single geographical area, as any two such will likely be in direct competition for a lot of things, so this would likely emerge as a regional thing, with different new human species rising to dominance on different continents, leading eventually to conflict or uneasy trade when we do eventually come into contact with each other again across such geographic barriers.

This also points to a potential danger with ETIs, should we ever actually encounter any: we will likely be in direct competition. In nature, it’s rare for species to coexist that compete directly for the same resources; usually one or both shift their specializations, for example to different food sources that both exist within their ranges, or else one of them goes extinct.

It also means that humans might be destined to supplant the entire biosphere eventually. We compete with more and more things for more and more things: we got fire, we started eating meat a lot more and systematically wiped out almost every other large predator; large herbivores in the denser-populated parts of the world have largely been displaced by humans and domesticated livestock; as of photovoltaics, we now even compete with plants for sunlight as an energy source. In the end, that may mean that either it’s not possible to survive without the biosphere as we know it, nor to coexist with it, and we’re doomed, or else it is and everything else is doomed (at least to eventually being confined to zoos and aquaria, except for whatever else we end up assimilating as we did dogs, cats, pigs, cows, horses, and such).

Or: perhaps the human ability to make conscious moral choices will win out over seemingly iron laws of ecology and evolutionary biology. We started to protect, rather than wipe out, large predators in many areas after a certain point in our history. And a more-civilization-capable future human species might have a stronger and more consistent moral compass than our current species does. If such emerges, and isn’t outcompeted by true-hive-humans, it will likely outcompete the other alternatives — or integrate them as a well-treated citizen class with certain other rights but not the vote, as children are treated now. It may well grant such rights to animals, and even to other kinds of things, maybe not individual plants but forests, rivers, and other ecosystems.

Perhaps all such will have an attorney appointed who is compelled by the legal bar’s ethics code to faithfully represent their client’s best interest, even if that client is an intertidal zone or a herd of wildebeest rather than a human being of any species, and who is empowered to acquire and spend resources on said client’s behalf and to bring suit on their behalf — a full power of attorney, an appointed legal guardian, not only the client’s lawyer. The client may receive payments, ranging from welfare to payments for ecosystem services rendered, that are held in a trust controlled by this representative, who would be required to spend the funds to preserve and tend to the client in whatever way is indicated by expert consultants, ecologists and biologists and others with suitable specialized knowledge who can serve as the client’s “nervous system and brain”, speaking for those who can’t speak for themselves, and also enjoined from misrepresenting the client by a professional ethics code and mechanisms of accountability to that code.

In the end, it is likely that only a system like that — a kind of “ecological personhood” system — sustained by a less venal and corruption-susceptible future humanity will be compatible with a thriving biosphere and human civilization, rather than the extinction of one or both, or of humans altogether. It is on this that I pin my hopes for the more distant future.

Besides the preservation (thus far) of lions, tigers, and some other large land predators, another thing that gives me hope that this outcome is not too improbable is this: we may already (slowly) be getting less corruption-prone with time. Improving at the civilization skillset and whatever genes underpin the capability. Those human populations able to maintain a more stable civilization for longer have been able to amass more resources and outcompete, including militarily, less stable ones. Though, also, those more aggressive toward outgroups have tended to also do so, it has also been advantageous to be more civilized toward ingroups.

That might be partly why we have such a stark polarization between conservatives and everyone else: the evolutionary solution to this conundrum hasn’t been the hive-insect one, but, because ingroup/outgroup distinction has been too fluid to base on pheromones or “race” or similarly, has been to have a population with a mix of two types of individuals, “xenophobes” and “diplomats”, and social structures that have usually put xenophobes in charge of foreign policy and diplomats in charge of domestic. But of course putting diplomats in charge of foreign policy has often resulted in mutually-beneficial trade, so that compromise may be giving way to an all-diplomats strategy that is superior in an environment of resource abundance. The problem being, resource abundance may have been all too temporary …

<snicker>

(So simplistic!)

“That might be partly why we have such a stark polarization between conservatives and everyone else: the evolutionary solution to this conundrum hasn’t been the hive-insect one, but, because ingroup/outgroup distinction has been too fluid to base on pheromones or “race” or similarly, has been to have a population with a mix of two types of individuals, “xenophobes” and “diplomats”, and [blah blah]”

Two types of individuals, right.

(Heh)

@ 9. I expect everyone already knows the reference here but just in case not :

Source : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silent_Spring

See also :

https://blueandgreentomorrow.com/features/book-review-silent-spring-rachel-carson-1962/

Plus another very relevant wikipage :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decline_in_insect_populations

PS. Time for a modern updatate or version of it? I guess PZ is toobusy to write one but..

Today I live in a small village in Germany, pop. 300. I’ve been growing up in a family of avid gardeners with a love of insects from the earliest years of my life. It’s devastating so see the loss of habitat and dwindling plant, insect and bird populations everywhere. By carefully choosing the right plants, our garden has become an insect oasis in a desert, so it is possible to change something at least around ourselves, or so it seems. Because the garden of my parents on the fringe of a small city has been tended equally carefully and insect – minded for at least 30 yrs now, but there all pollinators are dwindling fast and this and last year the vegetable crop was markedly reduced: lots of flowers, scarce fruit. In the gardens around them nobody seems to care or have the time and energy. Insect and plant populations seem to get isolated from each other. In the fight against despondency I plan to try some guerilla gardening around both locations. Hope springs eternal.

Just found this article this morning. It’s really scary just how delicate the balance is and how easily it’s thrown off by abrupt changes in climate (both macro and micro level changes) and how it creates so many significant and negative trickle down effects.Tragically, nearly half the population doesn’t care. https://www.mprnews.org/story/2024/10/01/minnesota-trees-in-turmoil-due-to-drastic-seasonal-changes

I have been saying since I was 14 that humanity will fuck things up so badly that we will cause our own extinction.

Thirty-five years later and I’m still right.