I don’t know about this Salon article, “A microscopic evolutionary arms race is happening between sperm”. It’s OK, but it put me off in the introduction.

As world-enlightening as Darwin’s ideas of natural and sexual selection were, there’s a tiny whiff of failure about him as a scientist. Brilliant as he was, he never realized that natural selection and sexual selection aren’t quite enough to explain evolution.

That’s just wrong. He didn’t get everything right, and he certainly didn’t explain everything about evolution, but he was humbly self-aware of that fact. There is no “tiny whiff of failure” associated with a scientist failing to explain the totality of evolution. If that were the case, every scientist ever would reek of failure. That passage reads more like the author is surprised by new discoveries in the field, and is projecting her own disappointment that a single book from 1859 was not comprehensive.

Also, nothing in the article is a new discovery. Sperm competition has been a known phenomenon for at least as long as I’ve been a biologist. There was a long-running aversion to the whole concept of polyandry, thanks to Darwin’s Victorian heritage, and I’m sure you can find some old relics in universities somewhere who want to think that sexual selection is all about brawny masculinity battering any competition into submission, but that’s just not the way most species work.

The author redeems herself at least in part by discussing spiders.

Perhaps because they’re easy to catch and breed, much of the research about sperm competition has been done on spiders. February 2022 work from biologists at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich and Aarhus University in Denmark shows the benefit to mating males of long copulations. When a male nursery web spider (species Pisaura mirabilis, found all over Europe) offers a female a “nuptial gift” of a silk-wrapped bug, she allows him to copulate. What’s more, she lets him continue to flood her receptacle with sperm for as long as the proffered meal lasts. In an email, co-investigator Dr. Cristine Tuni explained the logic of this adaptation. The spider’s ejaculate doesn’t arrive as a brief, happy burst and then stop. Rather: “In this species, sperm is transferred continuously over time from his copulatory organ into hers,” Tuni says. “So, the longer a male has his organ coupled to a female organ, the more sperm is transferred. The relationship is basically linear.”

One egg sac can carry hundreds of eggs. Because of this, any male wanting a big bang for his f**k probably intuits that size (of the gift) matters. Pumping as much semen as possible can help send his DNA on its way.

Malabar spiders

The Malabar spider (Nephilengys malabarensis, found in Asian rain forests) wields a far more dramatic sperm competition adaptation. Each male has two genital appendages extending from behind the mouth. As semen pulsates out of one, the spider detaches it and leaves it inside the female’s receptacle. Even severed like that, the genital continues to ejaculate. Meanwhile, it also plugs the receptacle, making it difficult for another male to get a genital in. Ready to fend off anyone who tries, the mating male stays on the web near the female. Unfortunately for him, each female’s semen receptacle has two openings. He has only plugged one. This means that, if a rival approaches, the mating male will have to fight fiercely to keep him at bay. To that end, and while ejaculation from the abandoned genital continues, many males eat their only remaining genital.Of course, that seems like a counter-intuitive strategy. Why get hungry at that very moment? Why hurt yourself right when you may need all the energy you can muster?

A team of biologists from several institutions in Europe and Asia seem to have an answer. They compared the battle survival rates of spiders who’d severed one genital to those of spiders who’d severed one and eaten the other. Additionally, they tested the battle survival rates of genitally intact males. The name of the team’s paper — “Eunuchs Are Better Fighters” — says a lot about why, under duress, a Malabar spider would eat its only remaining genital.

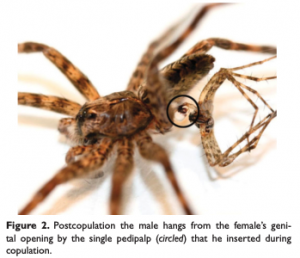

Unfortunately, it doesn’t discuss one of my favorite peculiar spider mating habits. Dark fishing spider (a common species in my area) males, once they succeed in mating to the point where they’ve inserted one palp into the female’s epigyne, spontaneously and abruptly drop dead. The palp is locked in place and the corpse continues to dribble sperm, but the poor guy is totally deceased, and eventually the female will notice the small dead male’s body dangling from her genitals and eat him.

Remember those horrible 80s comedies that were obsessed with teenagers desperate to lose their virginity? I like to imagine the obnoxious male protagonists having all the sexual properties of Dolomedes.

If we’re going 80s, Dolomedes needs an 80s soundtrack. “Who would’ve thought that a [spider] like me could come to this?”

…now I wonder if there is a good match for Kiss Me Deadly. “I didn’t get laid. I got in a fight.” has got to fit something. Maybe all 80s MTV hits are really about spiders’ mating habits.

Dear Prof. Myers,

What is the scientific name of the spider in this picture? (taxonomy is important)

https://assets.amuniversal.com/7b0f56c0d4c3013ab2e7005056a9545d

Having been told how a spider eats, I now wonder how an aspiring eunuch eats his remaining ‘thingy’? Does sqrt(h)e kill it first by inserting venom? Or does half-him just stab it, and slobber up his own still swimming spiderunculae? And does that ingested spunk supply it with the adrinaline to fight off a contender?

Methinks enough stuff for a doctoral dissertation.

adrenaline

Oh good lord! Please tell me that Baker & Bellis are wrong about human sperm competition. I can’t believe Salon printed this BS.