As I’ve mentioned before, I have a small amount of experience doing reptile population surveys. The basic method is the same whether you’re dealing with lizards, snakes, or turtles – you try to catch and measure as large a proportion of that population as you can. If your method of capture is some kind of trap, then you’re probably also going to be recording other species that get caught. This can be a problem because it takes a fair amount of effort. If you’re looking for one species in particular, you might not want to waste your limited resources catching every turtle in a pond, only to find that your species was never there. How can we just… check and see if it’s present?

Obviously, we cast a scrying spell.

Specifically, we can look at what’s being called eDNA – environmental DNA. See, we animals are rather messy organisms. We’re always shedding bits of ourselves everywhere we go. For us land-dwellers, this ends up as the mix of particles, microbes, and shed skin cells we call dust. In water, in theory, we should be able to detect that “dust”, at least from those creatures that live there. A team from the University of Illinois tested theory to help them find alligator snapping turtles:

The research team knew alligator snapping turtles were in Clear Creek, a southern Illinois stream feeding into the Mississippi River, because they put them there. A reintroduction program has put 400 to 500 young turtles into the system since 2014 and work is ongoing to determine the introduced population’s viability.

Each turtle is outfitted with a tracking device. To find them, researchers have to walk or kayak around the site with a less-than-waterproof radio receiver, set up and check traps, and interact with potentially dangerous snapping turtles.

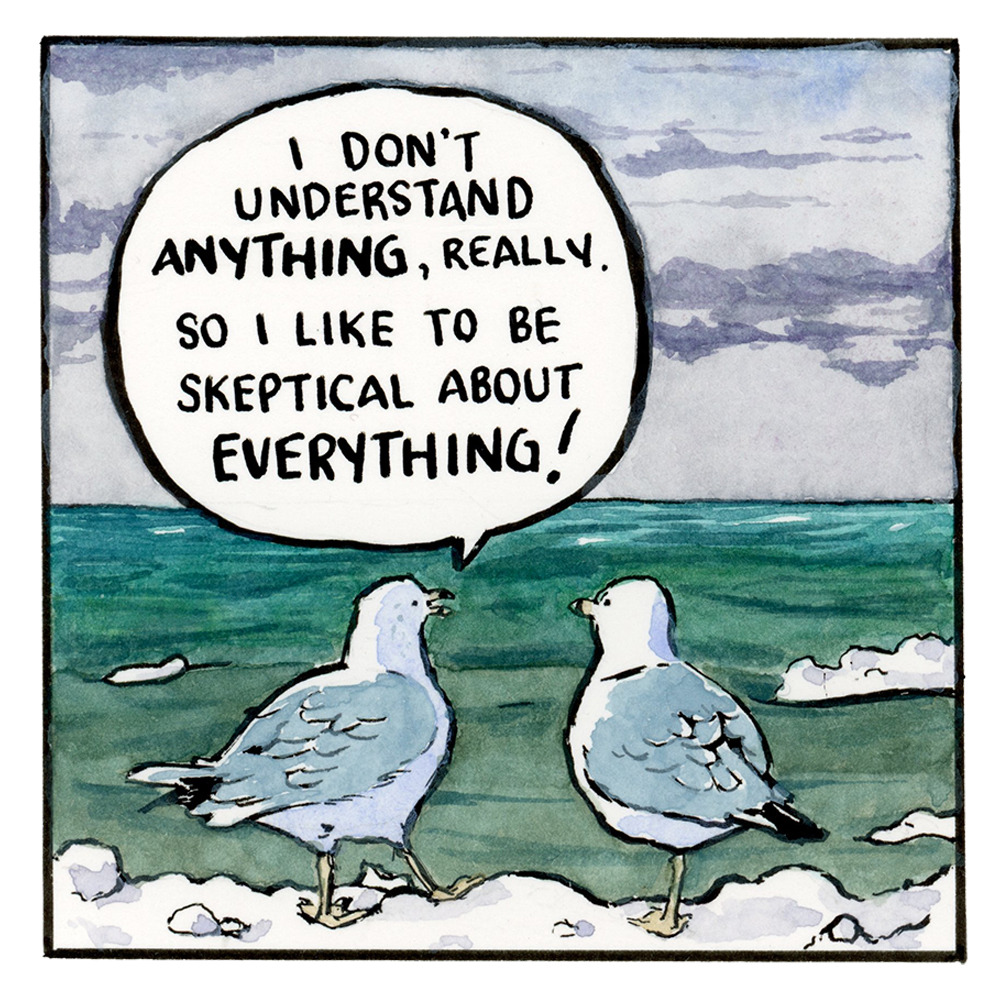

Prehistoric monster, Photo by Seth LaGrange who apparently went back in time to get the picture.

“It’s time consuming and a lot of effort. And we’re limited by the number of traps that we can check in a day,” Kessler says. “With eDNA, we can just show up at a location and pull a quick water sample. You can cover a wide geographic area relatively rapidly. That saves money, too, considering the cost of traveling to these remote locations.”

To prove eDNA is capable of detecting alligator snapping turtles, the research team first identified genetic markers that matched all of the subpopulations across the species’ range, but differed from any other turtle species. After radio-tracking each turtle, they took water samples near the turtles as well as in dozens of random sites to determine how eDNA travels in a riverine setting.

The eDNA method was able to detect alligator snapping turtles up to a kilometer, or two-thirds of a mile, downstream. Remarkable, considering less than a gallon of water was taken from each sampling location.

“This was a great place to test the performance of eDNA, because there are only so many alligator snapping turtles in Clear Creek, and we know where many of them are. That gave us something like the control of a laboratory experiment, but under very natural conditions in a real ecosystem,” Larson says.

The study also identified shortcomings of the method. For example, the researchers found that stretches of the river that were exposed to more sunlight represented gauntlets of DNA degradation.

“We know ultraviolet light destroys DNA, but we didn’t know how much the sun would affect our ability to detect alligator snapping turtles,” Kessler says. “We ended up finding that UV exposure does have a slight effect on our ability to detect. It’s reducing the copy number, or the amount of DNA, in our samples.”

Even with reduced copy number in some samples, the researchers were able to detect the elusive species with fairly high fidelity. The results suggest eDNA detection could be used as a first step to find turtles in locations where their status is unknown.

This technique wouldn’t have helped with any of the research projects in which I was involved, but it’s not hard to see the myriad of potential uses for it. As we continue to try to monitor everything happening to this planet’s biosphere, I’m willing to bet we’ll be hearing more about eDNA as a non-invasive way to get an idea of a species presence in a given body of water. I don’t know to what degree it would work on dry land, but I’m sure someone’s looking into it.

Thanks to @cosmixstardust for sharing the article around! It’s always neat to see developments like this.