I talk a lot about the need for rapid systemic change, and I sometimes worry that I don’t do a good enough job drawing a line between the kinds of individual action for which I advocate, and the scale of change that I want to see in the world. I’ve been hoping for something to help build a sort of social momentum on climate change for a long time. Back in 2011 or so, I started advocating for members of the New England Quaker community who could, to contribute to a loan fund so members of that community could get zero-interest loans for stuff like solar panels, batteries, heat pumps, and so on. The idea was to have people pay back the loan out of savings on their power bills (always assuming they could afford to), and then contribute a little extra, as able, to grow the fund and help the next person. Ideally, over time, the number of people helped by that project would grow, and the speed at which they could make change would increase. There have definitely been a number of group efforts on solar panel installation since then, but I don’t know if anything that organized ever cropped up.

Since then, as you may have noticed, I’ve come to the conclusion that we need to address the systemic problems that are blocking climate action, but that basic principle remains the same – if you have the patience to do things right at the beginning, you build a movement that’s flexible, hard to eradicate, and capable of achieving great things seemingly overnight. Rebecca Solnit wrote an essay that discussed similar topics a while back, and she recently shared this cartoon illustrating a section of that essay.

I once titled an essay "The Slow Road to Sudden Change," because even what is imagined as overnight change or revolution usually had a long build-up. Mushrooms give us a great metaphor for this. pic.twitter.com/I8hXWX1jtM

— Rebecca Solnit (@RebeccaSolnit) August 12, 2022

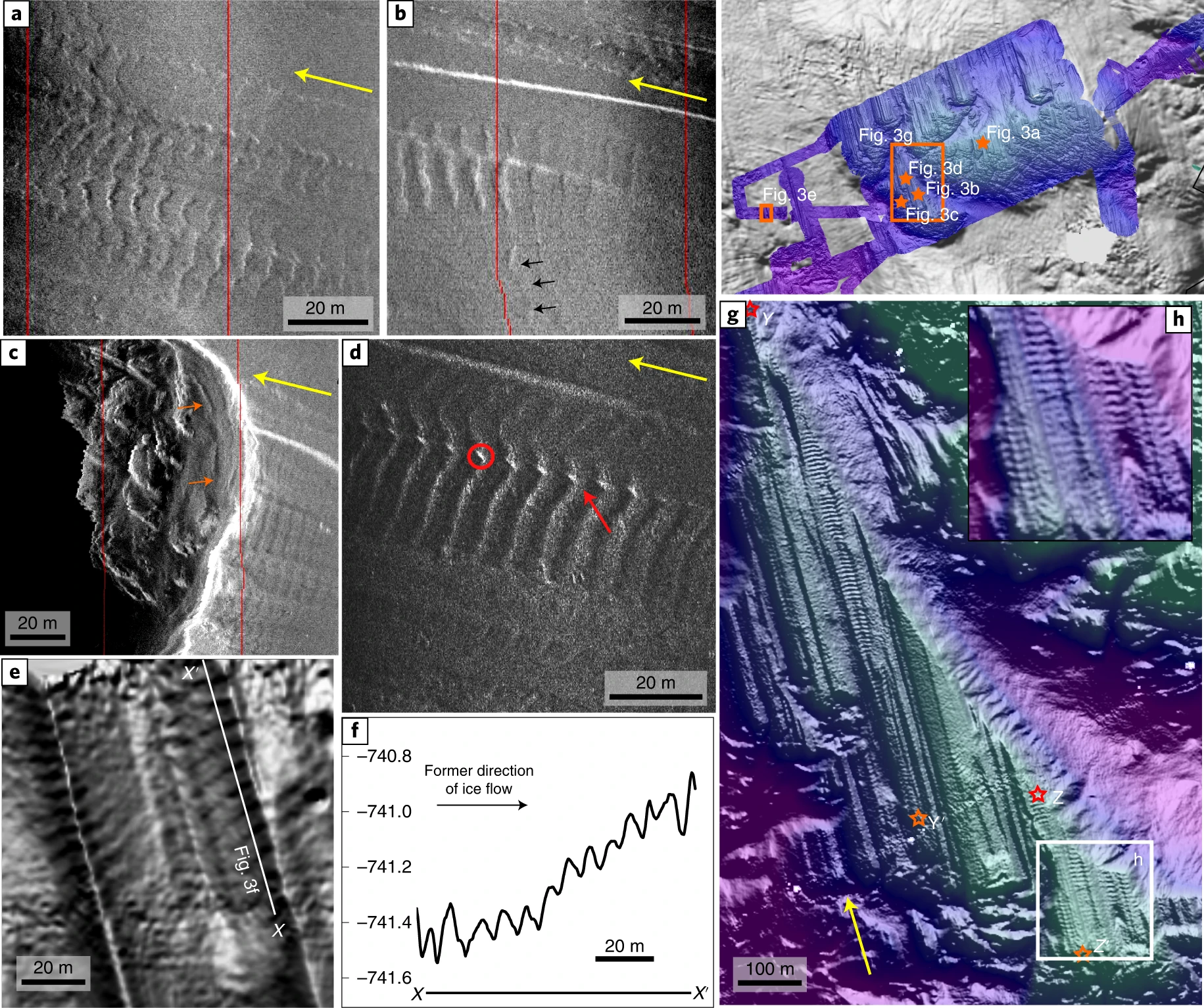

For those of you who can’t see it, the image in the tweet is three horizontal, rectangular panels, arranged vertically under the title, “Mushroomed:”. The top panel has a picture of a single mushroom, the second shows several in a cluster, and the third shows a cross-section of the soil, revealing all of those mushrooms to be part of the same organism lying beneath the soil. The images are accompanied by the following excerpt from Solnit’s essay:

After a rain mushrooms appear on the surface of the earth as if from nowhere. Many come from a sometimes vast underground fungus that remains invisible and largely unknown. What we call mushrooms, mycologists call the fruiting body of the larger, less visible fungus.

The passage in question then goes on to make the metaphor explicit:

Uprisings and revolutions are often considered to be spontaneous, but it is the less visible long-term organising and groundwork – or underground work – that often laid the foundation. Changes in ideas and values also result from work done by writers, scholars, public intellectuals, social activists and participants in social media. To many, it seems insignificant or peripheral until very different outcomes emerge from transformed assumptions about who and what matters, who should be heard and believed, who has rights.

Right now we’re at the foundation-laying stage. We’re forming those underground connections (called “hyphae“, if you’re interested), and extending our ability to interact, pool resources, and plan for the future. For me, this process is frustrating, and painfully slow, but it’s important to recognize that the small actions we take can be part of much larger change, especially of those actions are made with the larger change in mind. Altering consumer choices is an “individual change”, but it’s one that has proven itself to be incapable of supporting the more dramatic change that we need. To switch back to the building metaphor, it’s a weak foundation. It might support a small shack above, but any attempt at something bigger will collapse.

If you like the content of this blog, please share it around. If you like the blog and you have the means, please consider joining my lovely patrons in paying for the work that goes into it. Due to my immigration status, I’m currently prohibited from conventional wage labor, so for the next couple years at least this is going to be my only source of income. You can sign up for as little as $1 per month (though more is obviously welcome), to help us make ends meet – every little bit counts!