1. Never commit a crime unless you know you can get away with it. Otherwise you might end up in front of a jury, and juries are TERRIFYING. So are eyewitnesses.

2. If you want to read through research quickly, you can read the abstract and skip the methods and results reporting in favor of the discussion. This is particularly useful if you have four classes, each with daily readings, and want to get to the people who keep filling your inbox with interesting research. It’s unfortunate that it appears that even people who should read through all the mathematical analysis also fail to do this.

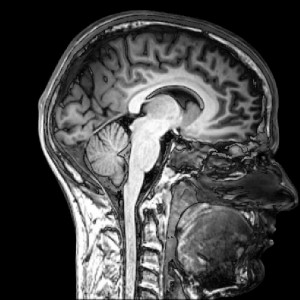

3. Brain pictures are very pretty. However, unless you have very specialized knowledge, this is about as much as you can offer when faced with a brain picture and little other information.

4. There are more than 100 neurotransmitters. However, there are less than ten that have familiar-to-the-public names. If you keep repeating this to yourself, headlines that read “TURNS OUT X WAS IMPLICATED IN BEHAVIOR Y” get exponentially less interesting.

5. If you’re unfamiliar with the prisoner’s dilemma, volunteer your services as a subject in social psychology studies. We’ll fix that for you.

6. Transcranial magnetic stimulation is awesome to watch until you realize that it’s a little tool that can disrupt your brain through the skull….and that your brain is fairly important for things like breathing and heart function, and TMS is “almost like a stroke” [If you’re squicked by watching people lose brain function, I wouldn’t click that link.]

7. Cohen’s d is a method for determining effect size. It’s also a great way for psych of gender researchers to make jokes while sounding serious.

8. Memory is fixed? Hahaha. ha. hah. Memory is only slightly less scary than twelve people determining your fate.

9. Trust nobody who tells you there’s a participant next door.

That something I’ve been wondering about psych studies; they tend to follow similar patterns. I feel like if I ever end up participating in one, I’ll either figure out whats going on, or think that I’ve figured it out, and screw it up.

Having recently read Fine’s A Mind of Its Own and reading Delusions of Gender, I have come to the conclusion that one should never trust a psych researcher when they are researching. And many of them don’t seem like they should be trusted in general either, at least not ones giving credence to entrenched stereotypes.

Oh man, I need to take another look at Delusions of Gender. Since I read it, I’ve taken a nicely stats-and-skeptic oriented look at gender research, and I’m curious to see how I feel about Fine’s writing now.

#2 speaks to me. As I am studying in social science and statistics, I noticed how fast social science students were at reading quantitative papers. It takes me a long time, since I try to understand the model enough to at least know how the authors reached their conclusions. Most students don’t do this. They don’t even try. I suspect many professors aren’t that much better (at least some of those who do not specialize in quantitative methods).

As was the case in the Guardian article, many social science researchers (I don’t know about psychology) choose overly complex models, adding a number of untestable assumptions to the mix. I blame ‘hard science’ envy, but I could be wrong. Overall, I understand the appeal of building an amazingly complex model, not to mislead people, but merely as an ego boost. I also have to fight with my tendency to operationalize in a way that suits my hypothesis, and I know I’m not alone (obviously).

I think departments that use a minimum of quantitative data should have *way more* applied stats/math classes (though I hear the US is marginally better at this than we are here in Canada). And classes critically evaluating quantitative research. I’m worried about the amount of people (academics or not) who automatically lend more credence to papers with incomprehensible statistical models.

I’m not sure we have much better standards. I will graduate with a degree from a research university, and I’ve taken a single statistics class. My next degree, which admittedly will handle less quantitative data, just requires that I have a B or higher in a stats class from the previous five years.

What’s Canada like?

As my professor in education science hammered into our heads: If somebody says their results were “very significant” or “highly significant” or anything with an adjective ibefore “significant”, you want to look for Cohen’s d.