The Probability Broach, chapter 12

[Content note: Mention of suicide.]

After their meeting with Bertram, Ed and Win pay a visit to their prisoner from the home invasion the other night, to see if he feels like talking:

First stop, Valentine Safe & Vault, where the thrifty shopper can get anything from a titanium can that’d hold both Thorneycrofts, to a tiny padlock smaller than a matchhead, guaranteed to withstand a full clip of .375s.

Most Confederate crooks post bond, not to assure appearance in court, but restitution to their victims.

How strangely gracious of them.

Consider the logic of this. If you’re accused of a crime, either you did it, in which case you obviously don’t care about the “laws”/customs of this society; or you didn’t, in which case you’re not going to have fond feelings toward the person who falsely accused you.

In either case, why would an accused criminal be so obliging as to put up a bond, when there’s no authority that can force them to do so? Apparently, L. Neil Smith expects us to believe that criminals in the North American Confederacy follow the rules and politely acknowledge, “It’s a fair cop” when they get arrested.

Valentine was in the hoosegow biz sort of by accident. Some client had ordered up a pair of cells, intended for the rare bird who wouldn’t make bond, then had gone bankrupt before the goods were delivered. Valentine had tried to make up the loss by renting them out.

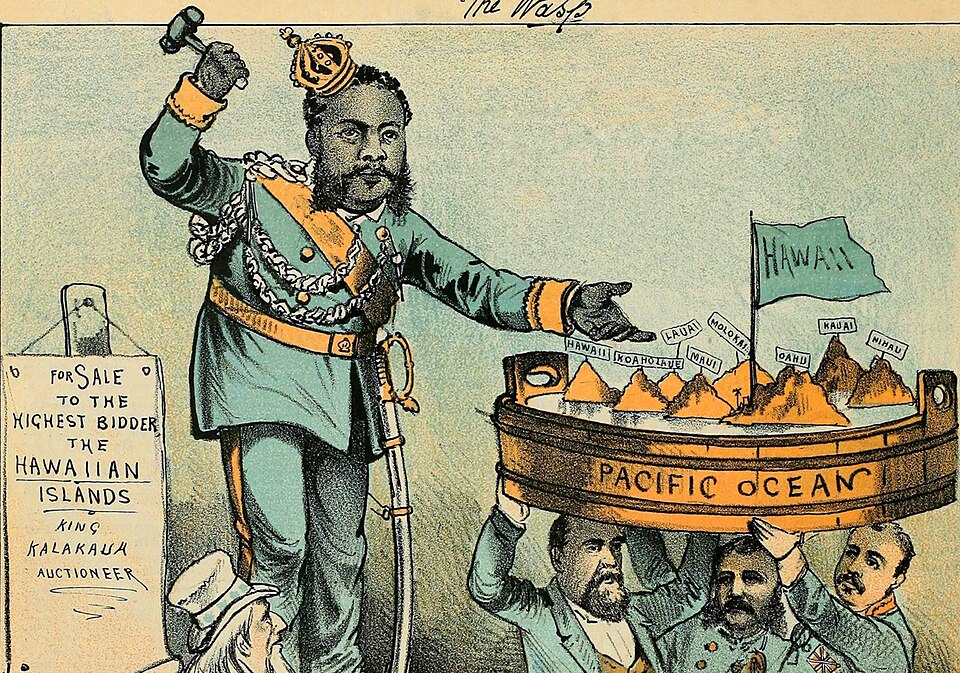

Smith implies that if you’re accused of a crime and can’t or won’t post a bond, you’re jailed until the trial. That seems normal and familiar – until you think about it, because the North American Confederacy is an anarchist society with no laws, police or justice system. Yet he writes as if the legal regime he scorns is still in effect.

If you’re accused of a crime, who sets the bond amount? This is supposed to be a free society with no coercion, so on whose authority can you be locked up?

The apparent answer, as we saw in a previous chapter, is that the private security firm you hire to protect you also adjudicates disputes. This includes detaining you until trial, if it’s a criminal matter.

But what if you don’t have a security company, or you refuse to say what yours is? Do they have to let you go? Or can the person who caught you just kill you on the spot?

This also ignores, as I mentioned, the predictable consequence that wealthy people would have impunity, because these firms would always side with their paying customers. They’d give them a slap on the wrist, or let them off with no punishment at all. Even if some firms tried to be fair, they’d quickly lose all their customers to less-principled competitors that promised their clients sweetheart deals.

The reason this doesn’t happen in real life is because there’s a justice system that won’t let you stonewall forever. If you harm someone, you can be prosecuted or sued in a court with the power to enforce its judgments. If you have an insurance company that indemnifies you, they can be forced to pay up. But in Smith’s world, these companies are a law unto themselves. There’s no higher authority that can force them to do anything.

When Ed and Win arrive at the private, for-profit jail business (just try not to shudder at the thought of that!), they get some bad news. Like other fanatic cultists from fiction, their prisoner committed suicide rather than face interrogation:

Penology’s scarcely a science here, but Valentine hadn’t taken precautions any two-bit county calaboose would consider elementary. Our prisoner, subcontracted to Valentine’s by his insurance company, had torn up a bedsheet and hanged himself in the night.

“And this makes money for me?” I asked, unsure what Ed was talking about as we bellied up to the counter.

“It better. You put that bullet in his leg, so I listed him as your prisoner.” He fixed the manager with a frosty glare. “It’s just as if he’d escaped.”

Worse, the prisoner refused to give his name or address (and his insurer also refused to identify him – further evidence that security firms will do favors for their customers), so they have nothing to go on. Their investigation has hit another dead end.

The silver lining is that the proprietor of the lockup owes Win compensation for this inconvenience: three hundred and seventeen gold ounces’ worth, according to the text. Under Ed’s glare, he grudgingly agrees to pay up:

“Say, bud, where do you want this forfeit credited?”

“Good question. Ed, where do they send your money?”

“Mulligan’s. But hand them a second ‘Bear, Edward W.’ and I’ll never get balanced again!”

I felt around in a pocket for the Gallatin goldpiece. “Then how about the Laporte Industrial Bank?”

This is one of those little throwaway lines that has gigantic implications. Let’s analyze it.

“Mulligan’s” is presumably a reference to Midas Mulligan, the banker from Atlas Shrugged, but that’s not the line I was talking about.

I was referring to Ed Bear’s dismissive remark about something that’d actually be a big problem in this anarcho-capitalist society: How do they handle people with identical names?

It seems like the only means of identifying people is by name. There are no Social Security numbers, nor any other government ID scheme that could be used to disambiguate people. Biometrics would be an option, but that’s out too; remember, they don’t know about fingerprints in the NAC.

So, how do you handle it if you’re a banker and your bank has a thousand John Smiths as clients? How do you know which account to apply a credit or a debit to?

Again, the seemingly-obvious answer is that private companies could develop their own ID numbers and tracking schemes, like credit card numbers. But if that’s Smith’s solution, he never says so. As we just saw, Ed Bear believed that his bank wouldn’t be able to deal with two accountholders who had the same name.

This should be impossible. You can’t run a high-tech industrial capitalist economy on a first-name basis.

Dozens or hundreds of different companies, and thousands of workers, are needed to manufacture all the parts that go into making something sophisticated, like a computer or a jet plane. For this to work, you absolutely need ways to identify and keep track of people, so that goods, services and payments all get routed to the right places. Otherwise, the flows of commerce would seize up, accounting would be a nightmare, and long-distance trade would be inefficient to the point of impossibility. And just try to imagine how stock and bond trades could work!

As we saw last week, Smith handwaves all this complexity away. He claims that most Confederate citizens run small businesses out of their homes in their spare time, doing business with their neighbors on a handshake. Yet, somehow, they also live in a hyper-advanced, highly-organized society with interstate highways, interplanetary travel, immense skyscrapers, and massive scientific endeavors like transdimensional portals. It just doesn’t add up.

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series: