The Probability Broach, chapter 15

This chapter opens with another of Smith’s fictional quotes put in the mouths of real historical figures. This one is attributed to Sequoyah (who in real life was the inventor of the Cherokee syllabary, but wasn’t an anarchist political theorist as Smith labels him).

“Are two people healthier than one person? Are two wiser? Then why believe they have more rights? History’s sadness is that sanity, wisdom, justice—the very qualities that make us human—are not additive, while one’s brute animal ability to do another injury, is. Two people are, tragically, stronger than one. Stripped to naked truth, that is the basis for all government, dictatorial or democratic. Can we not do better?”

—Sequoyah Guess

Anarchism Understood

Can two people be wiser than one? Yes! Was that even controversial?

It can go either way, to be fair. There’s such a thing as mob mentality, but there’s also such a thing as the wisdom of crowds. As a libertarian, you’d think Smith would be in favor of that: it’s always been proposed as an explanation for why free markets work, how it can be true that individual ignorance combines to produce a collectively rational result.

The wisdom of crowds is also why nations are governed by legislative bodies rather than kings, and criminal trials have a jury rather than leaving the verdict in the hands of a single random individual. There’s always a risk that one person will make a bad decision because of bias, ignorance or some other idiosyncratic reason. With a larger group, it’s more likely that individual prejudices and whims cancel each other out to produce a reliable result.

Back to the plot: Ed, Win and Lucy have assembled at Lucy’s house (“I’d counted eight cats so far, one sleeping in Lucy’s bony lap, another making his way up the difficult north face of Ed’s shoulder. I was trying to keep a kitten from perching on my head”) to discuss their meeting with John Jay Madison, a.k.a. Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. It turns out Lucy remembers him from the Prussian war—they fought on opposite sides:

“The Red Knight of Prussia himself,” Lucy declared. “‘Twas his Flying Circus put me afoot back in thirty-eight. Never forget it—there we were: The Pensacola an’ the Boise flankin’ my Fresno Lady, bearin’ northeast outa Cologne. They—”

“But that’d make him at least—”

“Ninety-six,” Ed said.

(Lucy, meanwhile, is 136. The North American Confederacy has life-extension technology, so no one finds this odd.)

Win wants to know why Madison was addressing Lucy as “Your Honor”. She admits that she helps mediate an argument now and then for “catfood money”:

“Pay attention,” Ed warned, “she’s being modest. Lucy’s a highly respected adjudicator and member of the Continental Congress.”

… “A distinction,” Lucy intoned, “utterly without distinction. Congress hasn’t met in thirty years, and I’m hopin’ like crazy it won’t ever have to again.”

Ed and Win are hatching a plan to break into Madison’s place and search for concrete proof of his world-domination scheme. Since Lucy holds an official position with the NAC, Win asks if she could get them a search warrant, so they can do this in an above-board way. But, of course, she can’t:

“Winnie, I got no official capacity. Nobody does, not even the president of the Confederacy. She only rides herd on the Continental Congress, if and when… What you and Ed are planning is unethical, immoral, and—”

“Fattening?”

“I was about to say, illegal—if we were the legislatin’ kind, which we ain’t. You two get shot up in there, nobody’s gonna say a thing. Madison’ll be within his rights. Or, he could sue you right down to your bellybutton lint.”

“Well, what are we supposed to do while he’s taking over the planet?”

“Son, we gave up preventive law enforcement long before we gave up law.”

What Lucy is saying is that in the NAC, even if you have knowledge that someone is plotting a crime, there’s nothing you can do but stand by and watch until they actually commit it. Attempted murder isn’t an offense; only murder is. (This world runs on Sideshow Bob logic.)

In our world, if you’re shot and narrowly survive, there’d be a police report. You could describe the vehicle that the shots were fired from, testify that one of the attackers named someone named Madison as the ringleader. Detectives would collect forensic evidence from the scene. All of this would provide probable cause for a judge to grant a search warrant, which could either turn up further evidence or clear the suspect’s name.

Also, if the police find evidence that someone is planning a serious crime—let’s say, holding secret meetings where they discuss a plot to kidnap and kill a sitting governor—they can be arrested for that. (That’s called criminal conspiracy.)

You don’t have to sit on your hands and wait for a would-be criminal to actually hurt someone before anyone takes any action. Smith denigrates this as “preventive law enforcement”, but isn’t that what we should want? Police who prevent crime from happening, rather than just punishing the perpetrators after the fact?

Meanwhile, in the NAC, the protagonists can’t legally do anything at all. A criminal can plot their crime in exacting detail without having to fear any consequences. Even to investigate a serious crime that’s already occurred, you have to break the law by trespassing in the suspect’s home. (When police are outlawed, only outlaws will be police!)

Their only chance, as Ed explains, is to break in to Madison’s house and find something that retroactively justifies their doing so. He can sue them for burglary, but they can countersue for a bigger crime. He’ll end up owing them way more money, and potentially getting exiled if he can’t pay. Win describes this as, “The end justifies the means”—all things considered, a frightening attitude for a cop to hold.

This goes to show that “total freedom” isn’t a political position that benefits everyone equally. It’s a much bigger advantage for those with evil intentions.

The way that L. Neil Smith writes his anarcho-capitalist world, it’s not just that they don’t have police or law enforcement; it’s that the legal system actively forbids these activities, even if carried out by private parties. The ordinary evidence-gathering and investigating that law enforcement would normally engage in are against the law here. Anyone who attempts them is risking death or a punishing lawsuit.

Meanwhile, activities that would be serious felonies in our world are perfectly legal and allowable. You can recruit conspirators, plot crimes, threaten people, stockpile weapons—and nobody can do anything to stop you.

This is a good argument for the importance of the Hobbesian social contract. We all agree to surrender some freedoms, in exchange for the protection of a state that’s supposed to keep us safe from those who’d do us harm. Ironically, the plot Smith wrote furnishes a good illustration of why this bargain of civilization is worth making.

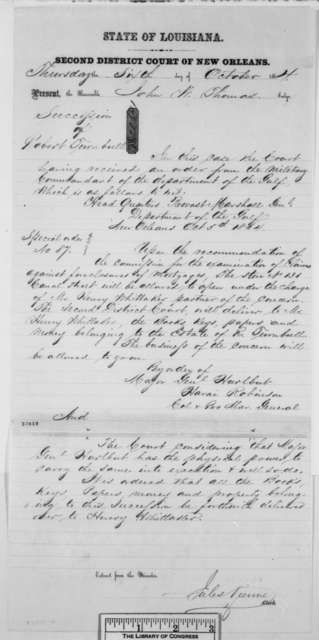

Image credit: Library of Congress

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series:

Who enforces exile?

Who enforces debt collection? Couldn’t a debtor move all their assets to a different name?

These are very good questions which the book does not answer. You just have to assume that criminals will be inexplicably cooperative.

Lucy fought the Red Baron in 1938. Did the war start later than WW I or is that it lasted a lot longer? And why does congress meet? What can it or does it do?

2)The ordinary evidence-gathering and investigating that law enforcement would normally engage in are against the law here. Well, no — I mean they have no law so how can it be illegal? It’s simply that it’s not authorized and protected in any way. Or am I wrong about how Smith’s fantasy world works.

3)Has Smith written all his books without any sort of editing or beta reading? Because that’s the first thing I thought of when he asserted the lone thinker is best.

4)So the Native Americans embraced anarchism too?

That’s a good point. Looking at the index, Smith says the Prussian conflict lasted from 1914-1918, so basically the same duration as in our world. Maybe 1938 was a typo?

Without too many spoilers, I’ll say that Congress pretty much can’t do anything, and this does become a factor later in the book.

It’s illegal in the sense that, if someone catches you trespassing in their house, they can shoot you on the spot or sue you for a hefty sum later. There don’t seem to be any extenuating circumstances that would permit you to argue in court that it was justified.

Ha! That line about how two people aren’t wiser than one could certainly be interpreted as a jibe at his editor.

Yes, we just stopped being racist against them in this timeline once we abolished government.

Putting Smith’s own words in the mouths of historical figures is kind of offensive, particularly here where Smith is so much less eloquent than the real man, and arguing so poorly to boot.

Lucy saying they gave up law enforcement before getting rid of law makes no sense. One implies the other, how did anyone think Smith knew what he was talking about? If I didn’t know better, I’d think he was actually arguing against libertarianism the whole time.

I am so glad that no anarchist desires the system shown here, and I bet that even most propertarians think Smith’s proposal is stupid, but I may be falsely assuming they have the minimal level of intelligence.

I presume, as the OP says, it’s about not restricting anyone’s freedom if they haven’t already committed the crime (or are suspected of).

I will slightly modify my previous comment. If “future actions do not justify present actions” is some kind of principle, then adjudicators would presumably take the view that just because von Richtofen was planning to shoot Lucy in the face tomorrow, that doesn’t justify breaking into his house tonight. I suppose that’s as close to “illegal” as anything gets.

But as there’s no statutory or case law, an adjudicator might as easily decide “Yeah, he needed killing” or the like (overlooking the potential for bribery and such).

Lines like ‘I was about to say, illegal—if we were the legislatin’ kind, which we ain’t.’ and ‘Son, we gave up preventive law enforcement long before we gave up law.’ also make no sense within the context of the story. They imply a familiarity with how our world works that these characters shouldn’t really have. (And yeah, this is far from a new problem for this book.) Sure, they’ve been told by Win what he thinks his world is like, but it hasn’t even been that long yet in-story; not only should they still be forgetting that ‘obvious’ things need to be explained to Win, they shouldn’t really know enough about what’s obvious to him to know exactly what explanation needs to be given.

I will grant that this isn’t an easy problem for a writer, especially since you’re writing for a set of readers who also won’t be familiar with the world, and the explanations are really for the reader rather than Win. Writing people with a fundamentally different set of basic assumptions about the world than you have is difficult.

But here the local characters are acting like they’re fans of a dystopian science fiction novel that happens to exactly resemble Win’s world and so they know exactly what they need to say. At this point they should still be stumbling over occasional ‘wait, what?’ things with Win like with some of the earlier accusations of how savage he was. I don’t care how complete Win’s explanation of his world’s history was, you do not just absorb that much history in that time. And the fact that so many people were apparently so bizarrely similar in both worlds should make it harder to keep them separate.

@jenorafeuer: Exactly. Everyone is happily living in a libertarian paradise that’s been around for longer than any of them have been alive, but at the drop of a hat, they have carefully-prepared speeches in a file-folder in their brains labelled “What to say if I ever meet someone from a statist alternate universe.”

If it’s socially acceptable for Ed to break into the Baron’s home and take the hit on a fine for burglary, as long as Ed finds evidence that Richthofen is up to something worse, then the Confederacy must have a real problem with people breaking into random pizza places looking for crimes in non-existent basements.

Conversely they’d have very little problem with people breaking into the places where such crimes are actually happening, because those places aren’t the basement of a mid-town pizza joint, they’re a mansion on a private island belonging to a billionaire, likely patrolled by heavily armed, well-trained security forces.

The anarcho-capitalists I’ve read all still proposed law enforcement (but private of course) and laws. I can’t remember any having an explanation of how things like search warrants would work however. Preventative law enforcement in general does seem like a huge problem in such a system (one of many). I recall Murray Rothbard (who’s basically the father of anarcho-capitalism) writing violating someone else’s rights could be justified retroactively if they’d violated yours to an equal or greater degree though, similar to Smith here. Smith almost certainly read Rothbard I would think. Still, he didn’t go into much detail.

Welcome back!