The Probability Broach, chapter 14

Win’s investigation of the people trying to kill him has hit one dead end after another. The only remaining clue, extracted under torture from one of the hitmen, is that the ringleader is someone named Madison. He grumbles about this with his friends:

“Well,” I answered glumly, “how do we find this Madison character, put an ad in the paper?”

Deejay looked up from her steak. “That wouldn’t be John Jay Madison?”

“Dunno, honey,” Lucy replied. “All we know is he’s the brains behind Hamiltonianism here in Laporte. You know a Madison?”

“Not really, but there’s one giving weekly lectures in the History and Moral Philosophy Department. My engineers were talking about it—something about the War in Europe from the Prussian point of view.”

It turns out Madison isn’t only not hiding, he’s in the phone book. His name and address are listed there, cross-referenced with the name of his group, the Alexander Hamilton Society (which we know is the evil organization behind the attacks on Win, because the assassins wore jewelry with the eye-in-the-pyramid logo). Somehow, not one but two detectives overlooked that incredibly obvious lead.

Win, Ed and Lucy go to pay Madison a visit:

So it happened that we glided up to the front gate of a mansion that made even Ed’s place look seedy, a Georgian monstrosity with a dozen sequoia-size columns and twice that number of marble steps leading to the door. We were greeted by a huge uniformed servant with close-cropped steel-gray hair and the accent of a comic psychiatrist. “Herr Madizon vill meed you in d’Ogtagon Hroom. Bleaze vollow me.”

You’d think Madison’s unpopular views would make him a pariah (naming your group the “Alexander Hamilton Society” in this anarchist society is like naming your group the “Adolf Hitler Society” in our world), but that’s not the case. Somehow, he owns a mansion even larger and more extravagant than the ones Win has already seen, and he has actual servants.

Maybe Smith thought that it would risk making his villain sympathetic if he lived alone in a small, decrepit shack. Are we supposed to infer that the way he flaunts his riches is a sign of moral depravity, even in an uber-capitalist world like this?

Madison is a huge man, tall and muscular, with a nasty scar down one side of his face. Despite himself, Win finds him charming: “it was impossible to hate this man” despite the “blood on his charming, well-manicured hands”.

He greets them politely and asks what he can do for them, to which Ed bluntly replies: “We’re more interested in discussing what you’ve already done. Two of your people were killed attacking my house night before last, and another killed himself yesterday morning.”

Madison seems amused, saying that even if it happened, it had nothing to do with him or with the Alexander Hamilton Society: “We’re simply an institution for the discussion and debate of political philosophy.”

Lucy rejoins that if that’s true, it’d be the first time Hamiltonians confined themselves to debate. Madison is offended:

“My dear Judge Kropotkin. You’re remembering, perhaps, our brief tenure in the Kingdom of Hawaii—brought to an untimely end by the Antarctican unpleasantness? Or the savagery with which our proposed reforms were met on the Moon, afterward?” He looked at her more closely. “Or, if I’m not being indiscreet, perhaps even the Prussian War? Your Honor, all of that was long ago, and your concerns now are unjustified on several counts.”

Madison says that it’s true the Hamiltonians have waged war in the past, but they’ve learned their lesson from their defeats and now only seek to bring about peaceful change. He laments that there’s so much prejudice against them:

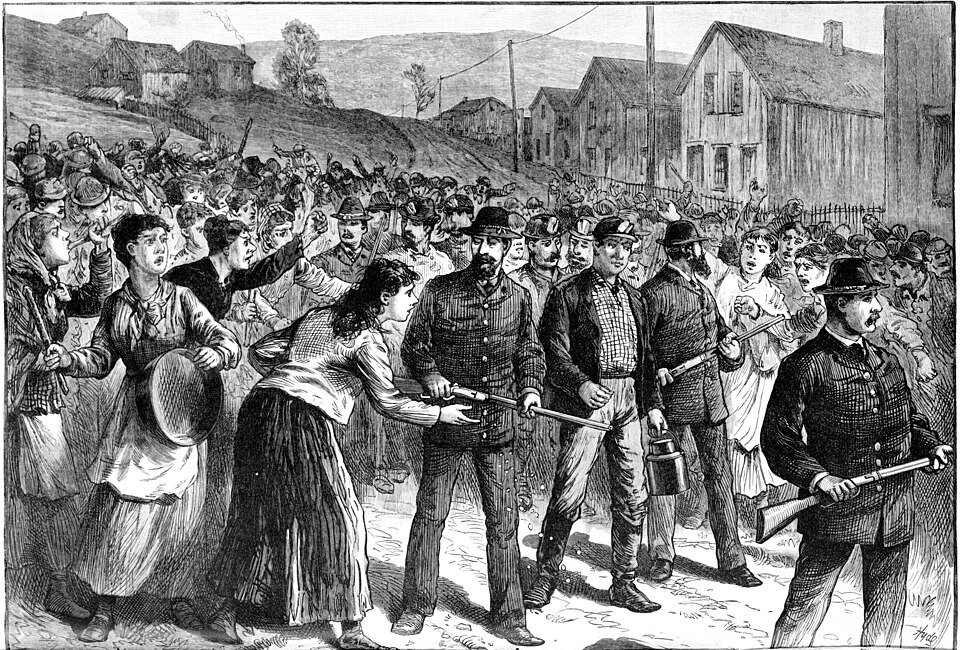

“[A]t various times in history, demagogues have required scapegoats. Unfortunately, we Hamiltonians have been handy on such occasions. It’s easy to condemn unworldly philosophers who have no ready means of reply. Since the Whiskey Rebellion, my fellows have been among the most unpopular in the world. What could we possibly say that would make people listen? How could we counter accusations graven in conventionally accepted history? Our views on economics and politics severely oppose the popular wisdom. Tell me, is that proof that we are wrong? To the contrary, it’s usually the other way around, isn’t it?”

“Very clever,” Ed said.

“And also very true. We believe that the good of society—in fact, the good of the individual—rests with recognizing and imposing an obligation to the state. We take what measures we can to transmit our views, hence this educational organization, my guest lectures at the university. But it goes very slowly: prejudice has such inertia.”

That’s true, of course. Conventional wisdom is often faulty and stubbornly resistant to change. Most people are set in their ways and refuse to be swayed by rational argument. While society as a whole does tend toward moral progress, it takes generations for new ideas to win out over old prejudices.

That makes it all the more bizarre that L. Neil Smith expects us to believe that Thomas Jefferson single-handedly talked the entire country into freeing the slaves, or that racism and sexism disappeared overnight when the federal government was abolished.

It seems that, in this book, prejudice only has inertia when it’s convenient for plot purposes. Whenever it would make his utopia look bad (say, for slavery to persist in an anarcho-capitalist paradise), people happily discard their bad beliefs as soon as they’re asked.

Remember, in the North American Confederacy, slavery is legal—not in the sense of “a written law says I can do this”, but in the sense of “if I’m powerful enough to do this, no one’s going to stop me”.

What if humans could be bought and sold in this world, just like any other commodity, and it was the Hamiltonians who were making the case to abolish it? What if they argued that we needed a centralized government to make and enforce laws protecting common people’s rights from the depredations of the extremely wealthy? (Which, needless to say, is exactly how abolition happened in the real world.)

That would be a genuinely interesting political debate for a novel set in an anarchist society. But it would create a level of moral complexity that Smith and other libertarians could never abide. Like Ayn Rand, he can only have a black-and-white political parable, where one side is solely made up of good guys who believe in freedom, and the other side is all mustache-twirling villains who want to create a brutal dictatorship.

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series: