Which is, perhaps, one thousand more than it deserves

When I was in high school, a friend loaned me a copy of Ayn Rand’s novel The Fountainhead – a lengthy tome about a superstar architect who defies the forces stacked against him to create the buildings that he wants, not the ones that the mediocratic hordes are creating. I remember being enchanted by the idea that someone could stand up for her/himself and refuse to capitulate to the opinions of popular demand. A major part of my personality has been informed (or perhaps reinforced) by the ideas I read in the book – the part of me that speaks my mind unashamedly and tries to be unfailingly honest in expressing my opinions.

Later, I read the Sword of Truth series by Terry Goodkind. While I enjoyed the series (except the last 2 books, which were steamy piles of word salad), the sixth book – Faith of the Fallen – really spoke to me. Its protagonist fights the good fight against a self-destructive ideology that punishes those that work hard and rewards malingerers and the lazy, by inspiring the people to reject the idea that mankind is inherently flawed and unworthy of dignity. This book, too, resonated with my sense that human beings should work hard to achieve, and that hard work and innovation should be rewarded. I was later to learn that the author was a Rand devotee, penning his own view on objectivism.

As I was completing my graduate studies, I read (well, as an audio-book) Atlas Shrugged, another novel by Ayn Rand. It sucked. It was awful. The writing was as stilted and awkward as the plot was circuitous and interminable. The plot twists were predictable, the ending plodding and unsatisfying, and there was a billion-page monologue from one character that could have been shortened to maybe 5 pages. I got none of the thrill that I had enjoyed from the other two objectivist works I’d read.

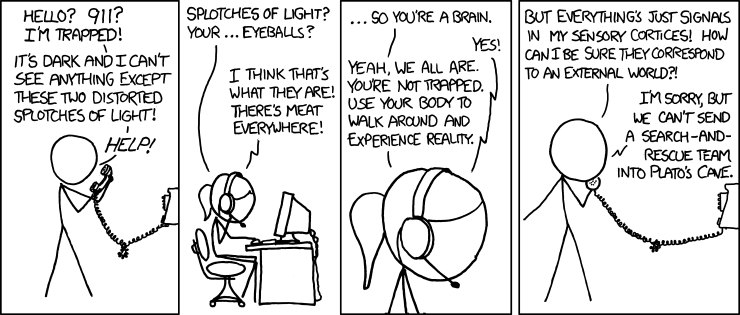

Reading Atlas Shrugged (a title which, incidentally, doesn’t make any sense since Atlas held up the sky and not the Earth), I lost any allegiance I had to self-identifying as an objectivist. The entire philosophy seemed to be based on a view of the world that is fundamentally flawed – creating false dichotomies and presenting people as caricatures rather than believable characters. Those who advocate for others are grasping, greedy leeches that feed off the righteous generation of resources that is the result of the hard work of an elite few. Those who produce are virtuous, upright, honest and fair-dealing – the only iniquity is seen by those that would attempt to sponge off the upright by exploiting a sense of “altruism” (which, to Rand, is just the application of guilt). Completely unexamined is the idea of someone producing goods by exploiting and abusing those with less wealth, or the idea of someone being given a leg up and turning that opportunity into a productive life. In Randian terms there are only the good guys (producers) and the bad guys (leeches) – and I suppose the hodge-podge of people who do manual labour and are employed by the good and bad guys alike.

Of course this kind of black-and-white world view appeals a great deal to a large number of people – particularly those that are millionnaires already. I’ve talked about this before, but it can be incredibly difficult to see the number of helping hands you’ve had along the way to success, and it’s very tempting to conclude that your achievements were gained simply by the sweat of your own brow. That’s so rarely the case as to be laughable – everyone has help at various stages, just as everyone has difficulties. Some people are born with innate abilities that make them more likely to be successful, others are born into familial privilege and are able to capitalize on opportunities to which others would not have access. There are many others that are born with one of these things but not the other. As we can infer from the type of nepotism, cronyism and pandering we see in our electorate and in industry, it’s much better to have the second than the first.

So what becomes of those who have no connections or privilege? In an ideal world, those that are born with inherent gifts are able to apply those abilities and achieve some level of success – success that can be passed on to their descendents. Ostensibly, that’s how those that are rich today gained their wealth. Those that cannot achieve greatness can at least work hard and have a decent standard of living, commensurate to their human dignity. That is a true meritocracy – where your level of success is dependent only on your natural abilities and the amount of work you put in.

However, we don’t live in a meritocracy. We live in the world – a world in which political favours are given to corporate entities based on lobbying and favouritism rather than who does the best job, and those at the top achieve greater wealth by defrauding those lower on the rung than they would by producing a superior product or service. Objectivism does not apply to a world like this – it speaks only to a world in which the only barrier between a person and her success is the amount of work she puts into her life. When people do not behave like rational free-market agents, objectivism can make no meaningful predictions about the world.

So is objectivism a complete waste of time? Are there no lessons that can be gleaned from Rand’s works? I don’t think that’s the case. Like the axioms of religion or admonishments of metaphysical philosophy, there can be great subjective value to be gained from reading Rand allegorically. Forgetting for a moment her insistence that her books are meant to portray real life events and people, we can certainly empathize with a person against whom the odds are stacked standing up and refusing to compromise her/his vision, provided we also recognize that when our vision impacts the lives of others, they also have a stake. We can recoil from anyone that insists that we have a moral obligation to give up what we have to those that don’t, provided we simultaneously remember that it is in our best interests as members of a society that people have the opportunities to do for self, and that our participation in that effort may be required. We can recognize that “profit” and “wealth” are not dirty words – rather measures of the success of an idea – provided that we scrutinize the practices of the wealthy to ensure that those without wealth are not being exploited or defrauded.

We can make the world closer to meritocratic, provided that we don’t try and take objectivism literally.

Like this article? Follow me on Twitter!