There is a concept in psychology called the “just world hypothesis”, also known as the “just world fallacy”. In its essence, this concept refers to our tendency to infer that the world operates as it should – goodness is rewarded and iniquity is punished. Where the fallacious component of this phenomenon crops up is when we allow this thought process to operate in reverse – those who are punished or rewarded must have deserved it, because the world just works that way.

This is a particularly attractive heuristic for a number of reasons. First, it is reassuring to think that we live in a universe where things exist in a state of balance – chaos is unsettling and potentially dangerous. Second, and perhaps most compellingly, it gives us a sense of satisfaction to think that the hard work we put in will be rewarded. It gives us even more satisfaction to think that those who do wrong will get their come-uppance in the end, a phenomenon called schadenfreude.

There is no place in which the just world fallacy is more obvious than in theology. Regardless of which deity we are talking about, there is always a balance between the forces of good and the forces of evil, with the good guys eventually winning out in the end. Christianity falls down this path most egregiously, with an accounting of a final battle and judgment that is the stuff of great myth; however, all the great religious traditions put great faith in the idea of ultimate balance. The very concept of an afterlife is an implicit reward for a good life or punishment for a life used for ill.

This fallacy pops up outside the realm of religion, however. It is this fallacy that allows us to look at the horrendous disparity between the living conditions of First Nations people, of women, of people living in starvation in southeast Asia and Africa, and rationalize it. Take a look at the comments section of any news report from that region (particularly about what is currently happening in the Ivory Coast), and you’ll undoubtedly come across someone with a brilliant statement like “well all of those African leaders are corrupt – what do they expect?”

It’s nice to be able to explain away injustice with such a simple wave of the hand. Doing so removes any sense of responsibility you might feel for the way corporations from which we purchase goods exploit and devastate those countries, destabilizing them to a point where corruption becomes de rigeur. It removes any feelings of guilt for the fact that our cities are built on First Nations land, much of which was obtained through dishonest treaty processes. It prevents us from having to feel remorse for propping up a misogynistic system that rewards men for fictitious “superiorities” that we have been told to believe we have. We can then go about our lives without having to constantly examine our every thought and assumption, which is an exhausting process that can prevent anything from actually getting accomplished.

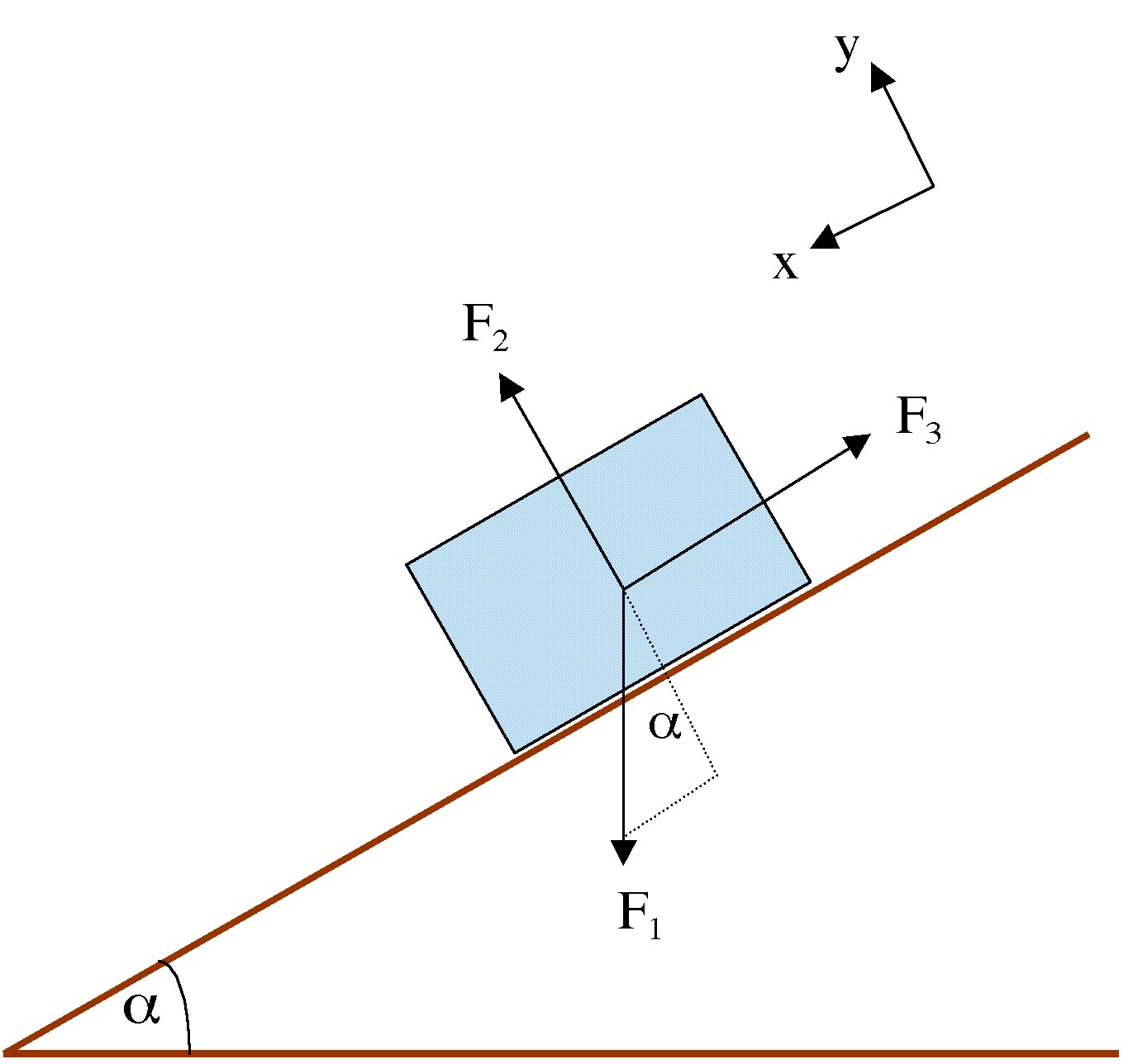

The problem with belief in the just world hypothesis is that it blinds us from seeing the world as it truly is. Consider this figure for a moment:

Anyone who has studied classical mechanics (called ‘physics’ in high school) will immediately recognize this as a free body diagram. The various forces at work on the rectangular object are presented. When we can identify the direction and magnitude of these forces, we can make meaningful predictions about the behaviour of the object. However, if we neglect one of the forces either in how strong it is or where it’s going, our predictions – indeed, our very understanding of the object – are fundamentally flawed (e.g., if we forget about friction, we would expect the block to slide down the ramp – friction may keep it exactly where it is).

Society and the people of which it is comprised can be thought of in much the same way. When we neglect to take into account the forces that are at work on us, our predictions and understanding of the world is meaningfully misconstrued. If we add in other forces that aren’t actually there, then we’re realy in trouble. The just world fallacy is just such an addition – it postulates the existence of an outside influence that inherently balances other forces that may result in unjust disparity. We are then relieved from any sense of responsibility to correct injustices.

The ultimate manifestation of this is the bromide “everything happens for a reason”. Starving kids in Ethiopia? Illegal wars? Abuse and deprivation? Exploitation of vulnerable peoples? Don’t worry, everything happens for a reason. Justice will win out in the end, without any need for action from you, safe behind your wall of fallacy.

It’s not exactly difficult to see why this view of the world is fundamentally dangerous. The world is not a fair place. In fact, “fairness” is an essentially human construction – sometimes animals are predated into extinction, sometimes entire ecosystems are destroyed by natural disasters, it’s entirely possible that entire planetary civilizations were wiped out by a supernova in some far-flung corner of the galaxy. These things are only “unfair” to human eyes – as far as the universe is concerned, them’s the breaks. I suppose there is some truth to the statement that “everything happens for a reason” – it’s just that this reason is that we live in a random, uncaring universe.

If we wish to live in a fair world – and I’d like to hope that we do – then it is incumbent upon us to make it that way. The only force for justice that exists is in the hands of human beings, and the only strength behind that force is the level of responsibility we feel to make it so. It is of no use to cluck our tongues and say “well that’s the way it goes” or “things will work out” – making statements like that is the same as saying “I don’t care about the suffering of those people”. If that’s the case (and oftentimes it is), we should at least be honest with ourselves and say it outright.

It is for this reason that I identify as a liberal – I am not content to let the universe sort things out. The universe doesn’t care, and there’s no reason to believe that the unfairness of random chance will result in justice for those that centuries of neglect have left behind. If we care about justice, then it’s up to us to make it happen.

Like this article? Follow me on Twitter!

TL/DR: The world is not a fair place, although we like to try and convince ourselves that it is. If we want to live in a fair world, then we have to make it that way.

Leave a Reply