[cn: non-explicit discussion of sexual harassment and assault]

A week ago, there was the #metoo campaign. It called for people who had experienced sexual assault or sexual harassment to say “me too” on social media, so that we might realize how common it is. It swept over Facebook for quite a while, so presumably most readers have already heard of it; I’m just recapping so nobody feels left out.

I didn’t say anything on Facebook, but here I will say, “Me too.” I have been a victim of multiple counts of sexual assault, including rape. It’s not a big deal for me to come out and say this, because I have been open about it for years.

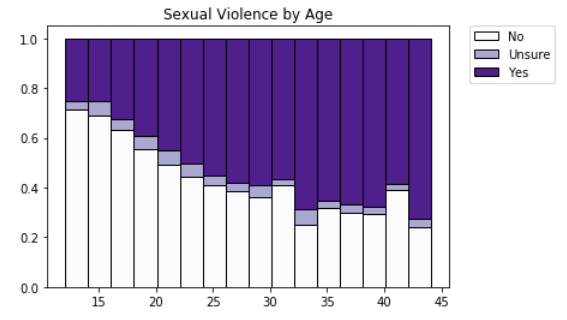

#Metoo was not a helpful campaign to me personally. I did not desire to participate, and I did not learn anything from it. I already knew lots of people have experienced sexual assault and harassment. I mean, I work on the Asexual Community Survey and produce graphs like this one.

Please do not take the numbers on this graph literally, and do not duplicate the image without citation to the report that it comes from. There’s a lot of additional context that changes its interpretation.

The plot suggests that about 70% of the ace respondents to our survey will experience sexual violence of some kind in their lifetime. It will be somewhat smaller in the general population, because the general population has more men and is less queer. (In our own survey, the straight non-ace people had rates that were about 10% smaller.) But no matter how we cut it, we’re talking about a very significant fraction of the general population. And that doesn’t even include sexual harassment!

This is all to say, if you really want to know how widespread sexual assault and harassment is, you can just look those numbers up. Believe those numbers. Internalize them. Now just pretend that X% of your friends said, “Me Too,” and you can save them the trouble of actually having to do it.

So, the title question: Who is #metoo for?

First and foremost it’s for the benefit of people who learned something from it. We saved those people the trouble of looking up statistics and internalizing them. And to be fair, that’s something I wouldn’t expect most people to do for themselves. Sifting through literature and sources takes time and effort, requires expertise, and can be done incorrectly. You might observe that I myself am deliberately avoiding a literature review now, because I just don’t have the time. It’s also very difficult to actually internalize the statistics, see the people behind the numbers. Having a bunch of friends say “Me too” is a much easier way to learn about and internalize the high prevalence of sexual harassment and assault, even if you don’t get any precise numbers out of it.

Even many victims of sexual violence cannot or will not internalize the statistics, despite it being an issue of personal relevance to them. For these people, #metoo could also be very helpful, as it shows them that they are not alone.

The #metoo campaign may also serve a function for some of the people who participated. For some people, it may be cathartic to come out and say it, and feel like you’re fighting for a cause larger than yourself. There is also safety in numbers. If you’re the only one speaking out, you become the center of attention; if you’re participating in a social media campaign, people place more focus where it should be, on the larger picture.

But to be clear, talking about horrible experiences is not cathartic in general. Perhaps it was cathartic for me the first time I said it, but I’ve already said it, and it isn’t cathartic anymore. I also point out that I was fortunate to not experience PTSD. PTSD is a reality for many people, and that means talking about it could feel like reliving it. Hearing others talk about it can be triggering too (which proves that it is impossible to optimize everyone’s preferences simultaneously). For me, talking about it is merely unpleasant.

If we look at the #metoo campaign as a transaction, we see that sometimes it is mutually beneficial. Victims feel catharsis, and their friends become more educated. In other situations, the transaction looks like a service performed by one person for the benefit of another. Victims are going through a difficult time in order to educate their friends.

Of course, “education” is a somewhat complicated service. We live in a world where plenty of people are all too happy to “educate” us with their opinions–and yes I know, I’m a blogger too. We often think of arguments as cooperative projects to search for truth and educate ourselves, but in reality the attempts to educate each other are part of a self-serving strategy in a game of power.

And it is no different with #metoo. When we educate people about sexual assault and harassment, it is for their benefit so they might go on to be more decent people. But there is also a self-serving ulterior motive. The hope is that not only will they go on to be more decent people, they will specifically be more decent to us. I hope that doesn’t come off as too insidious.

It is for everyone. Most people need it personalized. Numbers aren’t enough if someone doesn’t see it personally. Really, how would they know if they aren’t told it is happening?

That instinct is just as real as numbers.